29 Feb 2016

Feline otitis treatment update

Ariane Neuber describes cat ear diseases, and, failing successful antiparasitic therapy, suggests a systematic approach looking for a primary disease is adopted.

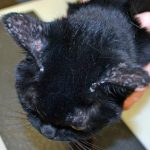

Figure 1. Lesions on the dorsal head and pinnae characterised by crusting, alopecia and erythema in a cat with pemphigus foliaceus.

Hearing is much more acute in cats than in humans. While the upper end of the human auditory range is typically between 16kHz and 20kHz, a cat’s ears can capture acoustical signals up to 60kHz from the environment. Hearing is, therefore, very important to cats, for hunting and other daily pursuits.

A variety of diseases can lead to problems with the ears, most commonly the ear canals, and, in some chronic and severe cases, can affect the hearing.

Compared to the dog, breed variation is negligible in the cat and breed predisposition due to ear conformation is, therefore, not important. However, some other differences to canine anatomy also exist, such as the relative short and straight ear canal, the shape of the manubrium (less curved) and the division of the feline bulla by an incomplete septum into a ventral and dorsal bulla. The septum contains a branch of the sympathetic nerve and, when damaged, results in Horner’s syndrome, which explains why this is at much greater risk of complication in cats with otitis or post-treatment.

Ear flushing, cleaning or using instruments in the middle ear can easily damage the septum. The septum also makes it harder for any matter in the ventral bulla to drain, leading to longer and greater exposure of delicate structures, such as the inner ear, and a greater risk of ototoxicity induced by medications, including cleaners or drops.

Pinnal diseases

Pinnal diseases, either traumatic (cat fights), due to solar damage or parasitic infestations, such as Sarcoptes, Notoedres or Neotrombicula autumnalis, are also very common in the cat. Traumatic wounds may require antibiotic therapy in some cases and good wound hygiene is important. Solar damage should be avoided by keeping the cat indoors during high UV light exposure times (for example, 10am to 3pm) or the use of a cat-safe sunblock preparation. Failure to protect cats can lead to solar dermatitis and, in some cases, squamous cell carcinoma. This is particularly important in cats with white ears tips and more relevant in regions with higher levels of sunlight than typically found in the UK.

Pinnal parasitoses can be frequently seen; however, Sarcoptes and Notoedres are very rare in the UK, whereas harvest mites are a common, albeit seasonal, condition and can usually easily be detected with the naked eye.

Pemphigus foliaceus

Pemphigus foliaceus commonly involves the pinnae (Figure 1) and large, often coalescent pustules and crusts can be found. However, the lesions rarely involve the pinnae alone and more widespread lesions are usually found to involve the face, nail beds, trunk and extremities. Cytology usually reveals numerous acantholytic cells and histopathology is needed to confirm the diagnosis. However, it is important to rule out other diseases that can cause separation of keratinocytes at the deeper levels of the epidermis, such as dermatophytosis or pyoderma. If indicated, antibiotic therapy may be needed and fungal culture and special stains on histopathology specimens should always be performed prior to embarking on immunosuppressive therapy.

Proliferating necrotising otitis

Proliferating necrotising otitis (Figure 2) is a rare skin disease in cats; however, it is more commonly seen in young cats. The aetiology is unclear and histopathology is needed to confirm the diagnosis in suspicious cases. Clinical signs include sharply demarcated crusted plaques usually on the pinnae, external orifice and, sometimes, vertical ear canal.

Topical tacrolimus has been helpful in some cases and, in some patients, the disease may also slowly spontaneously regress over months or years.

Mosquito bite hypersensitivity

Mosquito bite hypersensitivity is a seasonal allergic condition that predominantly affects the pinnae (Figure 3) and other body areas sparsely covered with hair, such as the paws. It is more frequently seen in warmer climates, so is relatively uncommon in the UK. Typical lesions include crusts, scaling, papules and ulcers. The patient is usually pruritic.

Mild cases resolve on their own if allergen avoidance is successful by restricting outside access during the times of day when mosquitos are most active – at dusk and dawn. Intermittent glucocorticoid therapy may be needed to reverse the inflammatory changes. Completely effective mosquito repellents are not available, although pyrethrin can be helpful.

Glucocortocoid therapy

Occasionally, long-term glucocorticoid therapy can lead to curling pinnae (Figure 4), which may be irreversible, and hormonal disease can cause pinnal alopecia (Figure 5).

Otitis externa

Otitis externa is a more common presentation in dogs than in cats. This may be due to the fact allergic skin disease is not quite as common in the cat as it is in the dog and allergic cats do not as commonly suffer from otitis associated with their skin disease. Hormonal diseases, such as hypothyroidism and Cushing’s disease, and keratinisation disorders, such as primary seborrhoea, are not commonly seen in cats. These are common causes of otitis in dogs.

Secondary factors (that is, the microbial component of the disease) are also in stark contrast with the situation in canine patients, with Malassezia being by far the most common organisms and Pseudomonas otitis being exceedingly rare. However, similar to the canine counterpart, the underlying disease needs to be investigated and treated alongside the infection and inflammation usually present.

Predisposing factors – that is, contributing factors that existed prior to the onset of the disease, but on their own would not cause any ear disease, such as pinnal confirmation, unsuitable ear cleaning and lifestyle (in dogs, swimmer’s ear) – are not usually of great importance in cats.

Primary diseases, such as allergic skin disease, cornification defect and endocrine disease, are much less common; however, ectoparasites can be seen quite frequently in the cat – predominantly Otodectes cynotis and Demodex.

Perpetuating factors include changes that have occurred due to the ear disease and cause it to be more likely to persist or recur.

These include changes such as stenosis – due to swelling of the lining of the ear canal, otitis media, ceruminous gland hyperplasia, increased humidity, excessive discharge, dysfunction of the epithelial migration, calcification of the ear canals, debris in the middle ear or a dilated or ruptured tympanic membrane – all much less commonly seen in cats.

Cytology is important to determine which microorganisms contribute to the disease and may be helpful in finding mites at the same time.

O cynotis

The most common primary disease in the cat is probably otoacariosis, caused by O cynotis (Figure 6). This is a highly contagious disease and affects young and older debilitated cats more commonly. Typically, a black coffee ground-like otic discharge is associated with the condition and the mites can usually be seen with the naked eye – often when performing otoscopy. Alternatively, an earwax preparation can be examined microscopically to identify the parasite.

Similar to many other parasitic diseases, the host response is an important part of the clinical picture in each patient. While some “silent carriers” can be found that harbour the mites without undue discomfort, some patients show a marked inflammatory response and present severely pruritic, with copious otic discharge and often a secondary bacterial or yeast infection.

Some ear drops are licensed to treat otoacariasis, such as:

- drops containing suspension-containing miconazole nitrate, prednisolone acetate and polymyxin B sulfate

- drops containing diethanolamine fusidate, framycetin sulphate, nystatin and prednisolone

Some spot-on preparationscontaining imidacloprid and moxidectin or selamectin are also useful.

Cleaning may be needed to remove the discharge and effectively reach all of the parasites. All in-contact animals must be concurrently treated, as failure to do so is likely to lead to residual mites on other hosts reinfecting the patient. Although mites are predominantly found in and around the ear canal, ectopic infestations have also been reported. The mite can live off the host for up to 10 days, which may also lead to reinfestation if treatment is not carried out for long enough.

Demodex

Demodex can cause otitis in some cats; however, it can also be found in some cats with just mildly increased cerumen production. In mild cases, therapy may not be necessary, but lime sulfur dips may be needed in more severe presentations.

Polyps

Inflammatory polyps (Figure 7) usually arise from the mucosa of the bulla or auditory tube, but can also break the tympanic membrane to cause otitis externa. They are non-neoplastic masses consisting of epithelial tissue, fibroblasts, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils, and can usually readily be identified cytologically due to the variety of cells present, as opposed to uniform cells encountered in neoplasia.

Chronic inflammation may be a contributory factor. Sensory deafness is seen in about a third of cases. Young cats are predisposed. Clinical signs correlate with the location of the mass and may include Horner’s syndrome, head shaking, deafness, head tilt, nystagmus, otitis externa, aural irritation and, in some cases, upper airway disease or chronic otitis.

Treatment is usually by ventral bulla osteotomy or traction/avulsion, with the latter showing a higher rate of recurrence, the incidence of which may be reduced by postoperative glucocorticoid therapy.

Foreign bodies

Foreign bodies are much less frequently seen in cats than in dogs, possibly due to the differences in anatomy. However, when a grass seed or similar is introduced into the ear canals, this can lead to sudden onset otic pain and secondary infection.

This can easily be resolved by removing the foreign body, cleaning the ear canal (if needed), as well as anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial therapy.

Neoplasia

Neoplastic changes can occur in any of the tissues of the otic structures – the pinnae, ear canal and middle ear. Often, CT or MRI imaging is required to investigate the extent of the lesions and a biopsy should be taken to identify the nature of the mass. Bulla osteotomy is often necessary to fully excise tumours in the middle ear.

Ceruminous cystomatosis

Ceruminous cystomatosis (also called ceruminous adenoma or apocrine cystadenomatosis) usually affects the pinnae, orifice to the ear canal and, sometimes, a portion of the ear canal as well. Lesions consist of papular, vesicular, nodular or plaque-like appearing changes. This is a non-neoplastic condition and is thought to represent congenital or degenerative and senile change. Persian and Abyssinian cats may be predisposed.

Due to the fact the lesions are space-occupying, they can partially, or even completely, occlude the ear canal, leading to secondary infections. The lesions contain a yellow/brown fluid, which can be expressed on rupture. Middle-

aged or older cats are more commonly affected and, in most cases, the changes do not lead to any discomfort for the patient. If problems occur, the lesions respond well to laser therapy. Surgical excision, cryotherapy and chemical cautery have been proposed as alternate treatments.

Therapy

Several ear cleaners are suitable to be used in cats and most proprietary ear drops are licensed for use in dogs as well as cats. However, due to the increased risk of ototoxicity, topical medication needs to be avoided if damage to the tympanic membrane is seen or suspected. Any harsher medications, such as dioctyl sulfosuccinate and other potentially ototoxic drugs, need to be used with great caution and, ideally, be avoided if possible.

Summary

Ear disease is rather less common in the cat than the dog. Many cases are caused by O cynotis; however, failing successful antiparasitic therapy, a systematic approach looking for other primary diseases is needed to treat it.