Deworming cats and dogs:

when, where and which worms?

Deworming cats and dogs:

when, where and which worms?

Image: Pedro Serra, NWL

Abstract

Whether and when we should use preventive deworming regimes in cats and dogs, and at what frequency, continues to be debated inside and outside the UK veterinary profession. When deciding which preventive deworming strategies to put in place, three worm types need to be considered:

- Toxocara species, because of their zoonotic risk

- tapeworms because of their potential economic and zoonotic impact, and

- Angiostrongylus vasorum, which can be highly pathogenic in dogs

Keywords: Toxocarosis, Echinococcus granulosus, Angiostrongylus vasorum, zoonosis, prevention

Contents

Routine deworming remains a fundamental component of preventive health programmes for pets across the globe.

In large parts of southern Europe and America, monthly prophylaxis against roundworms is routine due to the presence of heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis), and similarly in countries where Echinococcus multilocularis is endemic, monthly tapeworm prophylaxis is recommended due to zoonotic risk.

These parasites are not currently endemic in the UK and so when considering deworming frequency for UK cats and dogs, the zoonotic and pet health impact of key endemic helminths need to be assessed before making a recommendation.

Toxocara species, tapeworms and Angiostrongylus vasorum are the primary helminths in the UK that veterinary professionals need to consider. For each one, before deciding on deworming need and frequency, the following questions should be asked:

- Is prevention warranted?

Is a zoonotic impact present that needs to be limited or potential health impacts on pets? - Where is prevention warranted?

What does the distribution of the parasite look like in the UK? - Can it be achieved by means other than preventive deworming?

Removal of faeces, good hand and food hygiene and routine testing are examples. - If deworming is required, at what frequency?

This could be year-round, quarterly or monthly?

Angiostrongylus vasorum

Infection in dogs occurs most commonly through deliberate or accidental consumption of infected slugs or snails, but can also occur through the ingestion of paratenic hosts such as frogs.

Infection has also been demonstrated under experimental conditions to occur from ingestion of larvae present in slime trails, but the significance of this in natural transmission is unclear (Conboy et al, 2015).

Is prevention warranted?

Many infected dogs will either be subclinical carriers or develop mild to moderate pulmonary signs, including a cough (either productive or unproductive), and possibly dyspnoea.

An unfortunate minority of dogs, however, will develop a degree of coagulopathy potentially leading to spontaneous bleeding, uncontrolled bleeding after surgery or trauma.

Other potentially life-threatening signs may also develop, including thromboemboli. Pulmonary hypertension is less common, but another potential complication of infection (Koch and Willeson, 2009). Prevention is, therefore, warranted in dogs at high risk of infection.

Where is prevention warranted?

A vasorum has spread rapidly during the past 20 years across the UK, with cases often reported in practice and both prevalence and geographic range extending in fox populations (Kirk et al, 2014, Taylor et al, 2015).

The spread of A vasorum, though, is not uniform, with focal areas of very high prevalence and other areas remaining free of infection.

Case reporting sites, such as the one run by Elanco, have been useful in mapping areas of high prevalence and the introduction of A vasorum into new areas. Reporting of cases is only voluntary however, and distribution of infection is very fluid – with new foci forming.

In areas known to be endemic for foci, monthly preventive treatment should be seen as routine, especially prior to surgery.

In areas where endemic status is less certain, then testing of dogs prior to surgery – and in those with relevant clinical signs – will rapidly build up a picture of whether A vasorum is endemic in an area and whether routine preventive treatment for it is required.

Advice regarding testing for A vasorum can be found on the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) UK and Ireland website.

Can it be achieved by means other than preventive deworming?

- Geographical eradication of the parasite. The large fox and slug reservoirs of the parasite make this impractical. Use of molluscicides may increase the risk of exposure due to pets having access to dead slugs.

- Reduction of exposure to intermediate host. This is difficult due to the ubiquitous nature of gastropod intermediate hosts. Practical steps to limit exposure include keeping dog toys indoors, regular cleaning of outdoor water dishes and not walking dogs in wet conditions when slugs are likely to be active.

- Picking up of dog faeces. This is an important component of parasite control and may have some local impact on A vasorum exposure, especially as coprophagic slugs may be accidentally ingested by coprophagic dogs. The large fox reservoir, however, means that this strategy will have little impact on the amount of A vasorum circulating in any given area.

While these measures are likely to have some impact in reducing exposure risk, some exposure in dogs at high risk is still likely to occur and routine treatment is warranted.

If deworming is required, then at what frequency?

A monthly licensed moxidectin or milbemycin oxime product should be used in high-risk dogs, as no evidence exists that deworming at less frequencies has any impact on infection rates or disease.

At-risk dogs will include those in high prevalence geographic areas, as well as those at high risk due to lifestyle.

This includes dogs that deliberately eat slugs and snails and those that may accidentally ingest them though consumption of grass and coprophagia.

Tapeworms

Echinococcus granulosus, the cause of cystic echinococcosis (hydatid disease) in people, is a tapeworm of dogs with serious zoonotic potential.

Adult tapeworms are typically 5mm to 6mm (Figure 1) in length, with hydatid cysts then being found in intermediate hosts including ruminants, equines, pigs and man. Taenia species (Figure 2) in dogs have a similar life cycle, but are very large tapeworms with visible segments in the faeces.

Images: John McGarry, University of Liverpool

Intermediate hosts and location of cysts will depend on the Taenia species involved, but they are found in the offal and muscle of a range of ruminants.

Taenia species are similar in cats, but with prey animals such as rodents and lagomorphs acting as intermediate hosts.

The flea tapeworm Dipylidium caninum is another large segment shedding tapeworm of cats and dogs, with fleas acting as intermediate hosts.

Is prevention warranted?

Hydatid and Taenia cysts can lead to offal and meat condemnation in ruminants, with significant economic impacts for farmers.

Hydatid cysts in people infected after ingestion of microscopic tapeworm eggs from canine faeces can lead to serious pathology, with cysts forming in the liver, lungs central nervous system, bone and heart.

D caninum is also zoonotic, with human infection occurring through accidental ingestion of fleas.

Human infections are rare and generally well tolerated. Segments in faeces can lead to erosion of the human animal bond, and very large burdens can lead to loss of body condition and rarely intestinal obstruction in cats and dogs.

Where is prevention warranted?

Taenia species and D caninum infections are ubiquitous in the UK, with no known geographic risk factors.

Pockets of E granulosus endemic foci remain in the UK despite extensive attempts at control.

Herefordshire, mid-Wales and Western Isles of Scotland are known to be endemic, but surveys of abattoirs and hunting dogs in Britain suggest there are endemic foci in other parts of the country.

The location of these is currently uncertain, so prevention measures should be put in place for any dog whose lifestyle puts them at risk.

Control options other than preventive treatments

D caninum relies on the presence of fleas, so effective year-round flea control should be sufficient to provide adequate control against the parasite.

Treatment may be required if fleas are consumed during the consumption of prey animals or while infestations are brought under control.

Prevention of Taenia species and E granulosus relies on a range of measures, as compliance is unlikely to be 100% for any single measure. These include:

- Good hand hygiene. E granulosus eggs passed in the faeces are immediately infective, so good hand hygiene forms an important part of control.

- Not allowing dogs access to carcases and offal. This will also break transmission, but this not always practical in remote areas.

- Responsible disposal of dog faeces. This is important to limit intermediate host exposure.

- Feeding dogs cooked diets or pre-frozen raw diets. Where meat and offal has been frozen to -18°C for at least seven days, tapeworm cysts will be deactivated.

Routine deworming, however, is another important preventive measure in high-risk dogs to ensure tapeworm egg and segments shedding is kept to a minimum.

If deworming is required, then at what frequency?

Praziquantel is highly efficacious against Echinococcus and Taenia species, and therefore the tapeworm treatment of choice for routine treatment for cats and dogs.

The pre-patent period of E granulosus is 6 weeks, so this should be the minimum deworming frequency for high-risk dogs.

These include dogs allowed off lead in endemic areas and those with access to raw offal or livestock carcases.

Hunting cats require monthly tapeworm treatment to ensure Taenia segment shedding does not occur.

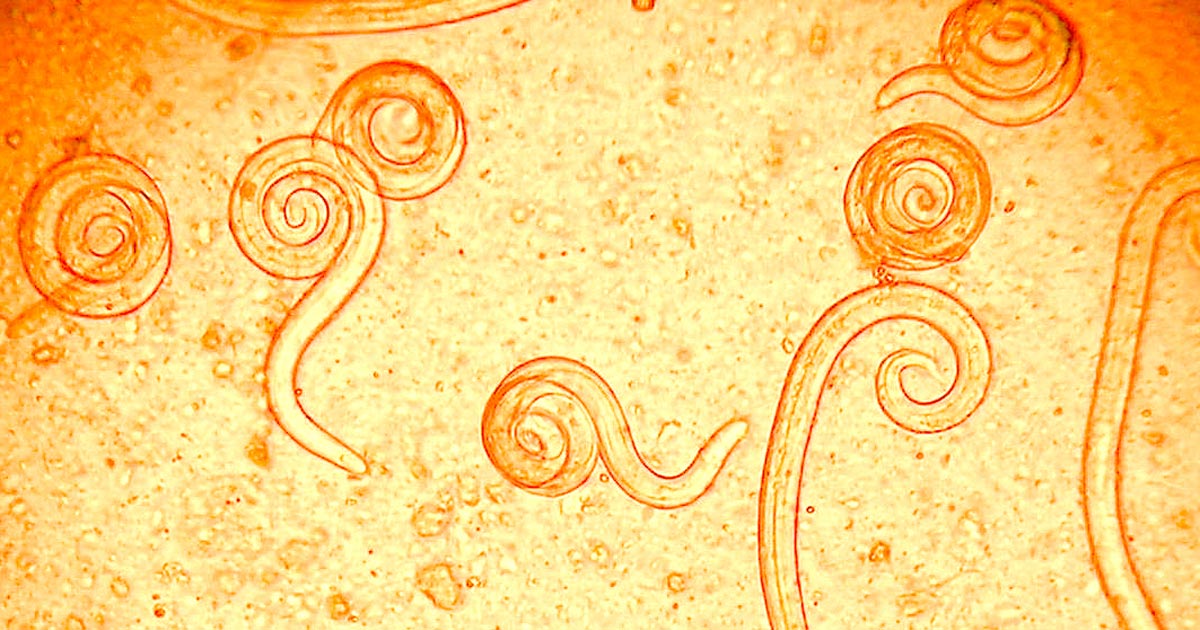

Toxocara canis and T cati

Toxocara canis and T cati roundworms (Figure 3) are ubiquitous, with almost all puppies, kittens and many hunting cats being infected prior to anthelmintic treatment.

The prevalence of patent infection in untreated adult cats and dogs is highly variable, with one UK study having found 5% of dogs and 26% of dogs to be shedding ova (Wright et al, 2016).

The eggs, when first shed, are unembryonated and are not infective. Progression to the infective embryonated stage is required for infection, so fresh faeces do not present a zoonotic risk.

Although cats and dogs are infected by ingesting embryonated eggs, the most important route of canine infection is trans-placental.

Dogs may also become infected by trans-mammary infection or consuming paratenic hosts such as rodents. The latter is more important in T cati transmission, where the feline host frequently hunts and trans-placental transmission does not occur.

Image © Todorean Gabriel / Adobe Stock

Is prevention warranted?

Infection is well tolerated by cats and dogs, although large worm burdens can lead to loss of body condition, respiratory signs secondary to pulmonary migration and, in severe cases, intestinal obstruction.

The primary concern with infection, however, is zoonotic risk. Once Toxocara species eggs develop to the infective stage in the environment, they represent a zoonotic risk that can lead to debilitation, blindness and increased risks of chronic conditions such as asthma, epilepsy and dermatitis if eggs are ingested.

This can occur through accidental or deliberate consumption of contaminated soil, fruit and vegetables, or through transfer of eggs from the coats of pets.

The basis of toxocariasis control is, therefore, to limit exposure to eggs and to reduce environmental contamination, which recent studies have demonstrated to be considerable in public spaces (Airs et al, 2022).

Control options other than preventive treatments

- Picking up of dog faeces. Responsible disposal of dog waste will also potentially limit environmental contamination.

- Covering of sandpits. To reduce cat faecal contamination, as does covering fruit and vegetables in allotments and gardens.

- Good hand hygiene. Washing hands, particularly before preparing and handling food, is advised.

- Washing of fruit and vegetables intended for raw consumption. Produce from gardens and allotments can easily be contaminated with cat faeces, and as a result should be washed before consumption.

- Feeding dogs cooked diets or pre-frozen raw diets. In the same fashion as for tapeworm.

These measures will not however, prevent exposure to Toxocara eggs on their own and routine deworming of cats and dogs is also required to minimise exposure.

Routine faecal testing at least four times a year can be used as an alternative to routine deworming, as long as the pet owner understands that egg shedding may go undetected in between tests – with potential zoonotic consequences.

If deworming is required, then at what frequency?

Puppies and kittens provide the largest source of potential infection. Treatment of puppies should start at two weeks of age, repeated at two weekly intervals until two weeks post-weaning and then monthly until six months of age.

Kittens should be treated in the same way, but the first treatment can be given at three weeks old, as no trans-placental transmission takes place.

With the exception of indoor cats that pose very little infection risk, ESCCAP recommends deworming adult cats and dogs every few months to reduce egg shedding.

High-risk cats and dogs, such as those hunting, or in contact with young children or immune-suppressed individuals, should be dewormed monthly to minimise the risk of egg shedding.

Conclusions

Lungworm, tapeworm and roundworm infections in UK cats and dogs warrant routine preventive deworming.

Which worms are targeted and at what frequency should be on the basis of a risk assessment and performed alongside other measures to minimise the risk of disease.

References

- Airs PM, Brown C, Gardiner E, Maciag L, Adams JP and Morgan ER (2022). WormWatch: Park soil surveillance reveals extensive Toxocara contamination across the UK and Ireland, Veterinary Record 192(1): e2341.

- Conboy G, Guselle N and Schaper R (2015). Spontaneous shedding of metastrongyloid third-stage larvae by experimentally infected Limax maximus, Poster presentation 2015, World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (WAAVP) Conference, Liverpool, UK.

- Kirk L, Limon G, Guitian FJ, Hermosilla C and Fox MT (2014). Angiostrongylus vasorum in Great Britain: a nationwide postal questionnaire survey of veterinary practices. Veterinary Record 175(5): 118.

- Koch J and Willesen JL (2009). Canine pulmonary angiostrongylosis: an update, Veterinary Journal 179(3): 348-359.

- Morgan ER, Shaw SE, Brennan SF, De Waal TD, Jones BR and Mulcahy G (2005). Angiostrongylus vasorum: a real heartbreaker, Trends in Parasitology 21(2): 49-51.

- Taylor CS, Garcia Gato R, Learmount J, Aziz NA, Montgomery C, Rose H, Coulthwaite CL, McGarry JW, Forman DW, Allen S, Wall R and Morgan ER (2015). Increased prevalence and geographic spread of the cardiopulmonary nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum in fox populations in Great Britain. Parasitology 142(9): 1,190–1,195.

- Wright I, Stafford K and Coles G (2016). The prevalence of intestinal nematodes in cats and dogs from Lancashire, north-west England, Journal of Small Animal Practice 57(8): 393-395.

Further reading