An expert perspective on cat parasites and public health

An expert perspective on cat parasites and public health

The Vetoquinol Scientific Roundtable Parasitology event, in Athens.

Abstract

As cat populations grow and become a more integral part of our human communities and homes, the unique role of cats in spreading parasitic zoonoses is becoming increasingly important. However, our understanding of cat parasites is lacking, compared to that of dogs.

Contents

The contribution of cats to public health risks was a core focus at the second Vetoquinol Scientific Roundtable Parasitology event in Athens, where more than 35 leading parasitologists, veterinary clinicians, and expert epidemiologists came together to share advances in feline parasitology and public health.

Discussions highlighted that cats pose different risks than dogs to human health and that more cat-focused efforts are needed in parasitology.

Clarifying cat population lifestyle terminology

Domestic/semi-domestic cats – Felis catus

- Indoor-only domestic cats – owned household pets

- Domestic cats with outdoor access – owned household pets

- Semi-domestic cats – owned or previously owned cats, but not looked after by one family

Non-domestic

- Community cats – not owned, fed by many people, often overlap with “semi-domestic” cats

- Stray cats – previously owned, but has strayed

- Feral cats – Felis catus – unsocialised, outdoor cat

- Wild cats – Felis sylvestris – and other wild cat species, unconstrained by humans in the natural life cycle

Cats’ contribution to human health risks

Cats’ natural habits – such as grooming and hunting, combined with increasingly close interactions with humans and their increasing popularity as pets – make them a contributor to parasitological zoonotic risk.

Roundtable participant Ana Margarida Alho, public health medical resident, ACES Lisboa Norte, Portugal, said: “Cats now live on our sofas and in our beds, and are more likely to be seen as part of the family.

“Behaviours like licking their owner’s face and cuddling with children are more commonplace. This means that the potential for cats to transfer and spread parasites and pathogens with zoonotic risk to humans is increasing.”

Simultaneously, many cats retain outdoor lifestyles with free roaming and close contact with wildlife. The mixing of urban spaces and natural areas is bringing cats into closer contact with wildlife and vectors, perpetuating parasites and disease spread (Candela et al, 2022; Smith et al, 2017). Whereas dogs are often under close human watch, cats’ activities are almost always unmonitored.

Moreover, there are a large variety of domestic and non-domestic cat population types whose radius of activity overlaps.

Each group contributes to disease risk and parasite spread in different ways through varying interactions with humans, other pets and wildlife, and differing levels of parasite control (Candela et al, 2022; International Animal Health Journal, 2022).

Participants agreed that parasitologists and veterinary staff need to tighten up terminology when describing cat populations, and better understand their lifestyles to help us accurately identify parasite and zoonotic risks, as well as recommending effective interventions.

Which cat parasites and zoonoses should be prioritised?

A few “common” parasites and zoonotic concerns were highlighted by the experts as important for veterinary teams to educate cat owners about and prioritise when it comes to parasite control:

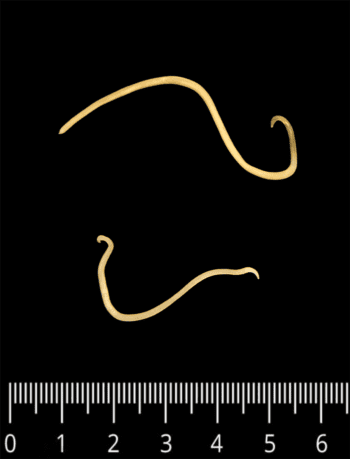

- Toxocara cati (cat roundworm)

- Ctenocephalides felis (cat flea)

- Dipylidium caninum (cucumber seed tapeworm – transmitted by fleas such as C felis)

- Bartonella henselae (bacterium causing cat-scratch disease – transmitted by C felis)

Role of T cati in public health

Toxocara is one of the most widespread zoonotic parasites and is listed as one of the five most important neglected diseases according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020).

T cati is ubiquitous in cats and can lead to toxocariasis in humans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). However, relatively little is still known about the prevalence of T cati and the risk to humans.

In the literature, prevalence data predominantly refers to the genus level Toxocara species only. However, recent research indicates the importance of the cat roundworm T cati as a greater public health risk than the dog species Toxocara canis (Otero et al, 2018).

Dr Alho presented findings from her research team, which showed more than 85% of Toxocara species detected in Lisbon’s children sandpits were identified as T cati eggs, not T canis.

A high seropositivity in humans (18.8%) was also found, of which almost 60% in children and young adults, indicating high levels of infection, or exposure to Toxocara species (Alho et al, 2021).

Roundtable participants agreed T cati needs to be accurately identified (for example, by applying molecular and serological tests) so that its contribution to human disease can be established and distinguished from T canis.

Levels of contamination in areas that cats defecate are often high. Research in Thailand showed 42 out of 50 districts sampled to be contaminated with gastrointestinal parasite larvae or eggs with Toxocara species accounting for the majority, in part due to the large numbers of community cats around the temples (Pinyopanuwat et al, 2018).

In general, prevalence data for feline parasites are useful to inform cat owners about the zoonotic risk and to encourage cat owner compliance with parasite control. To gain insight into prevalence on a local level, the frequency of tests for zoonotic feline parasites needs to be increased.

D caninum (flea tapeworm) – a difficult-to-diagnose zoonotic challenge

D caninum is another common yet often overlooked zoonotic parasite species.

Humans – usually children – become infected through the uptake of infective parasite stages promoted through close contact with infested pets (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). In addition, cats and dogs may transmit the larval tapeworms to people when they lick them, after biting fleas carrying the tapeworm.

Although it is considered a common feline parasite, the prevalence of D caninum is still unknown and varies significantly among different studies. Prevalence rates for tapeworm varied in the data presented – from 3.1% (Bourgoin et al, 2022) to 11.7% of domestic and stray cats (Zottler et al, 2018). However, D caninum prevalence is grossly underestimated as proglottids are not uniformly shed in faeces, and diagnostic methods such as faecal floatation are notoriously insensitive for detecting eggs of tapeworms, especially the egg capsules of D caninum.

As tapeworms are difficult to diagnose, they are often left out of parasite control protocols. Many popular products that prevent flea/tick infestations and some types of worms do not address tapeworms. This leads to owners having to use multiple parasiticide products and regimens, which can be challenging to reapply and maintain.

C felis (cat flea) – more than just an itchy nuisance

In addition to serving as the intermediate host for D caninum and causing hypersensitivities, C felis can carry a variety of other pathogens and are generalist feeders, commonly biting other animals and people besides cats. One of the most important is Bartonella henselae. Paul Overgaauw, specialist in veterinary microbiology and parasitology at Utrecht University, the Netherlands, highlighted: “Cats act as a reservoir for this bacterial infection, which is described as an emerging zoonosis.

“Veterinarians and doctors often forget the risk of flea-borne diseases to humans, which are often under-reported and underdiagnosed – fleas can cause more than associated dermatological issues. We’re seeing more B henselae in practice, and greater than 50% of cats are carriers of this bacteria transmitted through faeces and biting, scratching and licking of wounds (Álvarez-Fernández et al, 2018).”

The risk of Bartonella infection appears to be greater in veterinarians and clinic staff who work closely with pets, with studies showing higher seroprevalences compared to the general population (Lantos et al, 2014).

Symptoms range from asymptomatic bacteraemia to fever, endocarditis and potentially even death (Breitschwerdt, 2015). Veterinary staff should be aware that symptoms can be non-specific: one study showed Bartonella-positive veterinary staff reported a headache or irritability more frequently than uninfected subjects (Lantos et al, 2014).

Immunocompromised veterinary staff are more likely to become chronically affected or develop severe symptoms than immunocompetent individuals (Breitschwerdt, 2015). Experts call for this flea-transmitted bacterium to have greater recognition and be made a research priority.

Cat-scratch disease in humans

B henselae infection in humans can have localised or systemic features. Signs and symptoms include (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022):

- Fever, swollen lymph nodes (one to three weeks after exposure) and pustules.

- In rare cases – particularly in immunocompromised people, infections of the eye, liver, spleen, brain, bones, or heart valves can occur.

One study found it to be an important infectious cause of fever of unknown origin in children (Jacobs et al, 1998).

Improving education and compliance

Parasite control in cats is still poor worldwide. Roundtable participants agreed many owners are unaware of the zoonotic risks associated with cats (Kantarakia et al, 2020). A perception exists that cats “are clean” and “look after themselves”, which is one of the barriers to implementing regular parasite control, along with the fact that it can be difficult to restrain cats for parasite treatment.

As a result, cats are often not dewormed based on lifestyle and parasitological risk, with the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) advising that cats with outdoor access are tested/treated at least four times a year (ESCCAP; 2022).

Worryingly, sometimes outdoor cats in higher risk groups may even be treated less consistently than indoor cats in lower risk groups (Miro et al, 2020). Data collected in Swiss veterinary practices revealed 29% of indoor cats were not dewormed at all, while 38% of outdoor cats were dewormed once or twice a year and 40% were dewormed more frequently (Schnyder, personal communication, 2023).

To improve compliance, Rachel Korman, feline specialist at Veterinary Specialist Services in Brisbane, advised: “It’s all about identifying the relative risk and educating owners about appropriate products that are easy to apply and administer. Reducing the number of treatments and negative interactions with their cats is really important for cat owners.”

Zoonosis

Fundamental knowledge about zoonoses among key audiences is lacking, with 85% of owners having never heard of the term “zoonosis” (Matos et al, 2015).

What role does the veterinary team have in a one health approach to cat parasitology?

The link between human and animal health is becoming more widely acknowledged. This one health approach is particularly pertinent to parasitology, with more focus needed on cat parasites. As we live more closely with cats, it is apparent veterinary teams play an increasingly important role in testing for, preventing and treating cat parasites as well as educating owners about zoonotic diseases.

This was summfarised by Emily Jenkins from the University of Saskatchewan Department of Veterinary Microbiology in Canada: “Dogs, cats, humans are all in this together. We need to learn from the diseases that we find in both. There are so many challenges to working at the one health interface between pets, people, and the environment, but so many opportunities.

“The veterinary team is in a wonderful place to stand at that interface. Specific to cats, our work shows that they are better sentinels for Lyme disease-carrying ticks than dogs, probably because of their closer relationships with wildlife such as birds and rodents.”

Key take-home messages

Key take-home messages for clinicians are:

- Talk to cat owners about endoparasite – as well as ectoparasite – control in the context of zoonotic risk. In many cases, routine protection is important for protecting their family as well as protecting the cat (for example for Toxocara).

- Keep in mind that treating outdoor cats also protects the health of the broader community – especially children.

- Remind owners that cats can be asymptomatic – routine parasite control can prevent them from spreading parasites “silently”.

- Discuss the cat’s lifestyle and habits with the owner. Consider hunting, interactions with wildlife, seasonal activity, and any outdoor access (including so-called “indoor cats”, which may also have some outdoor access) and conduct a risk assessment using the ESCCAP guidelines.

- Ensure that a cat’s parasite control plan includes tapeworms, which are often missed out of protocols.

- Routine testing of cats for common parasites like roundworm and tapeworm can help build a better picture of diseases in the local area and determine a cat’s parasitic risk. Remember, diagnosing tapeworm eggs is difficult as faecal flotation is insensitive.

- Use data to demonstrate the need for parasite control to clients. For example, research shows environments such as public parks are heavily contaminated with zoonotic cat parasites such as Toxocara species (Otero et al, 2018).

- Emphasise the importance of good hand hygiene to cat owners – especially when cleaning litter trays, handling food or gardening.

- Be aware that you and your clinic staff may be at risk of acquiring parasite or vector-borne pathogens.

Vetoquinol

Vetoquinol is committed to advancing veterinary parasitology, demonstrated through our ground-breaking launch of Felpreva, the first endectocide spot-on for cats to treat both internal and external parasites, including tapeworms, in addition to providing three months’ ongoing protection against fleas and ticks.

Vetoquinol works with leading parasitology organisations – the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites, the Companion Animal Parasite Council and the World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology – and we support key parasitology conferences across the globe to encourage progress.

The Vetoquinol Scientific Roundtable Parasitology is just one example of Vetoquinol’s commitment to sharing knowledge and stimulating discussion across the animal health industry to aid innovation.

- Felpreva contains tigolaner, emodepside and praziquantel (POM-V). See the datasheet at www.noahcompendium.co.uk

- The SPC and further information is available from Vetoquinol UK. Advice should be sought from the medicine prescriber.

Image © Olha Tsiplyar / Adobe Stock

References

- Alho AM, Ferreira PM, Clemente I, Grácio MAA and Belo S (2021). Human toxocariasis in Portugal – an overview of a neglected zoonosis over the last decade (2010-2020), Infectious Disease Reports 13(4): 938-948.

- Álvarez-Fernández A, Breitschwerdt EB and Solano-Gallego L (2018). Bartonella infections in cats and dogs including zoonotic aspects, Parasites and Vectors 11(1): 624.

- Bourgoin G, Callait-Cardinal MP, Bouhsira E, Polack B, Bourdeau P, Ariza CR, Carassou L, Lienard E and Drake J (2022). Prevalence of major digestive and respiratory helminths in dogs and cats in France: results of a multicentre study, Parasites and Vectors 15(1): 314.

- Breitschwerdt EB (2015). Did Bartonella henselae contribute to the deaths of two veterinarians? Parasites and Vectors 8: 317.

- Candela MG, Fanelli A, Carvalho J, Serrano E, Domenech G, Alonso F and Martínez-Carrasco C (2022). Urban landscape and infection risk in free-roaming cats, Zoonoses and Public Health 69(4): 295-311.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). DPDx – laboratory identification of parasites of public health concern – Dipylidium caninum, www.cdc.gov/dpdx/dipylidium/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Toxocariasis (also known as roundworm infection), www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxocariasis/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Bartonella henselae infection or cat scratch disease (CSD), www.cdc.gov/bartonella/bartonella-henselae/index.html

- European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (2022). Control of ectoparasites in dogs and cats, ESSCAP Guideline 03 (7th edn), www.esccap.org/uploads/docs/cgqtqpf1_0720_ESCCAP_GL3__English_v19_1p.pdf

- Ferreira A et al (2017). Urban dog parks as sources of canine parasites: contamination rates and pet owner behaviours in Lisbon, Portugal, Journal of Environmental and Public Health, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28947905

- Jacobs RF and Schutze GE (1998). Bartonella henselae as a cause of prolonged fever and fever of unknown origin in children, Clin Infect Dis 26(1): 80-84.

- Kantarakia C, Tsoumani ME, Galanos A, Mathioudakis AG, Giannoulaki E, Beloukas A and Voyiatzaki C (2020). Comparison of the level of awareness about the transmission of echinococcosis and toxocariasis between pet owners and non-pet owners in Greece, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(15): 5,292.

- Lantos P, Maggi R, Ferguson B, Varkey J, Park L, Breitschwerdt E, Woods C (2014). Detection of Bartonella species in the blood of veterinarians and veterinary technicians: a newly recognised occupational hazard? Vector Borne Zoonotic Diseases 14(8): 563-570.

- Matos M, Alho AM, Owen SP, Nunes,T and Madeira de Carvalho L (2015). Parasite control practices and public perception of parasitic diseases: A survey of dog and cat owners, Preventive Veterinary Medicine 122(1-2): 174-180.

- McNamara J, Drake J, Wiseman S and Wright I (2018). Survey of European pet owners quantifying endoparasitic infection risk and implications for deworming recommendations, Parasites and Vectors 11(1): 571.

- Miro G, Galvez R, Montoya A, Delgado B and Drake J (2020). Survey of Spanish pet owners about endoparasite infection risk and deworming frequencies, Parasites and Vectors 13(1): 101.

- Otero D, Alho AM, Nijsse R, Roelfsema J, Overgaauw P and Madeira de Carvalho L (2018). Environmental contamination with Toxocara spp eggs in public parks and playground sandpits of Greater Lisbon, Portugal, Journal of Infection and Public Health 11(1): 94-98.

- Pinyopanuwat N, Kengradomkij C, Kamyingkird K, Chimnoi W, Suraruangchai D and Inpankaew T (2018). Stray animals (dogs and cats) as sources of soil-transmitted parasite eggs/cysts in temple grounds of Bangkok Metropolitan, Thailand, Journal of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 41(2): 15–20.

- Smith BP, Hazelton PC, Thompson KR, Trigg JL, Etherton HC and Blunden SL (2017). A multispecies approach to co-sleeping: integrating human-animal co-sleeping practices into our understanding of human sleep, Human Nature 28(3): 255–273.

- Zottler EM, Bieri M, Basso W and Schnyder M (2019). Intestinal parasites and lungworms in stray, shelter and privately owned cats of Switzerland, Parasitology International 69: 75–81.