3 Apr 2023

Avian influenza: are you prepared to see pet poultry this season?

Image © Anton Dios / Adobe Stock

If owners are concerned about the health of their birds – in particular, any clinical signs that may be a differential diagnosis for avian influenza – they have been asked to contact their vet for triage in the first instance.

If avian influenza is suspected, it should be immediately reported to the APHA.

Due to the severity and unspecificity of clinical signs associated with this disease, and the fact many differential diagnoses for a severely unwell bird exist, vets are obligated to provide assistance under the RCVS code of conduct (3. 24-hour emergency first aid and pain relief).

Owners are encouraged to register their flock with the APHA and a veterinary surgeon, to be familiar with the code of conduct and to discuss their experiences with the RCVS when practices do not meet their obligations.

The bird should be triaged for avian influenza risk factors and more common causes of an “unwell hen” should be excluded before suspicion of avian influenza is assumed. For example, salpingitis, peritonitis, tumours and respiratory disease due to other causes are more common diagnoses than avian influenza.

If, after triage, vets suspect avian influenza then they are under a legal obligation to report cases to the APHA. The APHA will follow up with a veterinary clinical investigation and sampling if avian notifiable disease cannot be ruled out.

No automatic culling policy exists for avian influenza outbreaks in the UK. Birds will only be culled if:

- avian influenza is confirmed in the flock following laboratory testing of samples

- a veterinary risk assessment indicates a strong likelihood that a premises keeping birds has significant links to an infected premises where disease has already been confirmed (these links could be via movements of birds, poultry products, people, equipment or vehicles between the two premises)

Contact details can be found on the APHA; Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs; or Welsh or Scottish Government websites.

Clinical signs of highly pathogenic avian influenza

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) is called “highly pathogenic” for good reason, as the disease’s clinical signs are often severe. They differ according to the species of bird and can appear in various combinations, so a bird doesn’t have to present with all of these signs at once to be a potential suspect case.

It is important that poultry owners and veterinary staff are able to recognise the common signs of HPAI, and any suspicions should be discussed with a vet.

A full list of these signs and some images are available on the avian influenza pages on the GOV.UK websites.

Signs

Flock signs (birds sharing housing) include:

- Unresponsiveness – quiet birds that are unwell don’t want to come out and engage as usual, don’t come for treats as usual, sit around fluffed up and may rally temporarily, but will soon tire.

- Huddling – with each other or against coop furniture/equipment, in nests or around drinkers.

- Unexpected deaths – sudden and rapid increase in the number of birds found dead, with several other birds affected in the same shed or air space.

Signs typical with severe or notifiable disease in birds include:

- Neurological signs – these may be severe and include head and/or body tremors, shaking, twitching, incoordination and loss of balance, or be mild such as head nodding or appearing to be falling asleep.

- Twisted heads or necks – leaving birds looking up at the sky or sideways.

- Swollen heads – facial feathers may stick up in swollen areas.

- Blue discolouration – of comb, wattles and/or legs.

- Generalised weakness – birds are unable to remain standing for long, look drunk and may struggle to control their wings. They may droop their wings and/or drag their legs.

- Shivering – this is more likely to be tremors as birds don’t shiver when they are cold like people do.

- Bruising, blood spots or swelling – check in between the feathers for haemorrhages on shanks of the legs and under the skin of the neck.

- Severe dyspnoea – without evidence of ascites or space-occupying masses (birds have no diaphragm); especially if you see any of the other symptoms listed.

The following are signs typical with common diseases in hens. Individual birds with these symptoms, in an otherwise well flock, are very unlikely to be affected by HPAI. However, these signs are suspicious when combined with those previously mentioned or when multiple birds are acutely affected:

- Coughing, sneezing, gurgling, or rattling or gaping – especially in birds recently wormed for gapeworm.

- Focal facial swelling – for example, around the eyes.

- Ocular discharge.

- Reduction in laying.

- Loss of appetite or marked decrease in feed consumption.

- Sudden increase or decrease in water consumption.

- Recumbency and unresponsiveness.

- Lethargy and depression.

- Fever or noticeable increase in body temperature.

- Diarrhoea – discoloured or loose watery droppings.

It should, however, be borne in mind that some species such as ducks, geese and swans can carry the avian influenza virus, and spread it without showing any obvious signs of illness.

Is there a risk to staff seeing pet poultry in practice?

The current strain of HPAI is classified as low risk to humans. Pet birds in environments compliant with avian influenza housing orders are considered to represent a relatively low risk compared to avian wildlife.

Birds housed with good biosecurity that have been triaged for signs of HPAI should pose very low risk when entering the practice. Poultry carry many zoonoses and agents infectious to other poultry, so gloves and an apron should always be worn when seeing them in practice.

Ideally, birds should initially be seen outside, in outbuildings or other less-frequently used areas of the practice until suspicion of avian influenza is ruled out, followed by thorough cleansing and disinfection of any such areas using a Defra-approved disinfectant at the appropriate dilution rate as specified under the Diseases of Poultry Order, and the Avian Influenza and Influenza of Avian Origin in Mammals Order (Defra, 2023).

This is to reduce the likelihood of any restrictions needing to be placed on the practice in the event that a positive bird had entered the main building.

How can teams help protect the welfare of poultry?

In terms of how teams in general practice can help protect poultry welfare, invite members of staff to become the new practice poultry welfare officer, showcasing their leadership, collaboration and communication skills.

The aim of their role should be to maintain staff and poultry welfare by upskilling themselves, and disseminating information throughout the practice and poultry clients. This could include:

- signing up for APHA disease alerts (GOV.UK, 2021)

- following APHA on Facebook for links to informative client videos

- attending any relevant APHA avian influenza webinars (GOV.UK, 2022a)

- engaging in team meetings to update staff when relevant restrictions are in place – for example, prevention, protection, surveillance or other zones and housing orders

- regularly accessing avian influenza outbreak maps (APHA,2023)

- notifying reception staff when movement licences are required (GOV.UK, 2022)

- provide links to helpful resources for staff including those available from the BVA and British Veterinary Poultry Association (BVPA)

The poultry welfare officer can also advise clients on how to attend appointments safely and actions to take it they fall within a restriction zone and are unable to travel. Ideally, clients should be engaged at a personal level at each appointment, during “flu season” or not, to ensure they are prepared to maintain the health and welfare of their birds during future housing restrictions.

Clients should also be reminded of other legal obligations when keeping poultry.

What legislative requirements should owners be aware of?

Legislative requirements owners should be aware of in relation to poultry include the following:

- Kitchen scraps cannot be fed to pet birds.

- Pet poultry are classified as livestock, so cannot be buried at home. They must be disposed of via an appropriate approved route – for example, cremated or incinerated at an approved facility (GOV.UK, 2022c).

- Owners must comply with relevant avian influenza orders, including avian influenza prevention zones (AIPZs), housing orders or other outbreak restriction zones applied in their area. Owners within prevention and surveillance zones must acquire a movement licence from the APHA before transporting their birds out of a zone, even if the journey is to a veterinary practice.

Regarding an AIPZ or avian influenza housing order (AIHO), biosecurity measures should be followed. Also, regarding an AIHO and housing, a solid roof (or failing that an impermeable covering – for example, a tarpaulin) that prevents water ingress on to the birds, and a structure that excludes access by wild birds and rodents, would be ideal.

In-practice tips

Vets

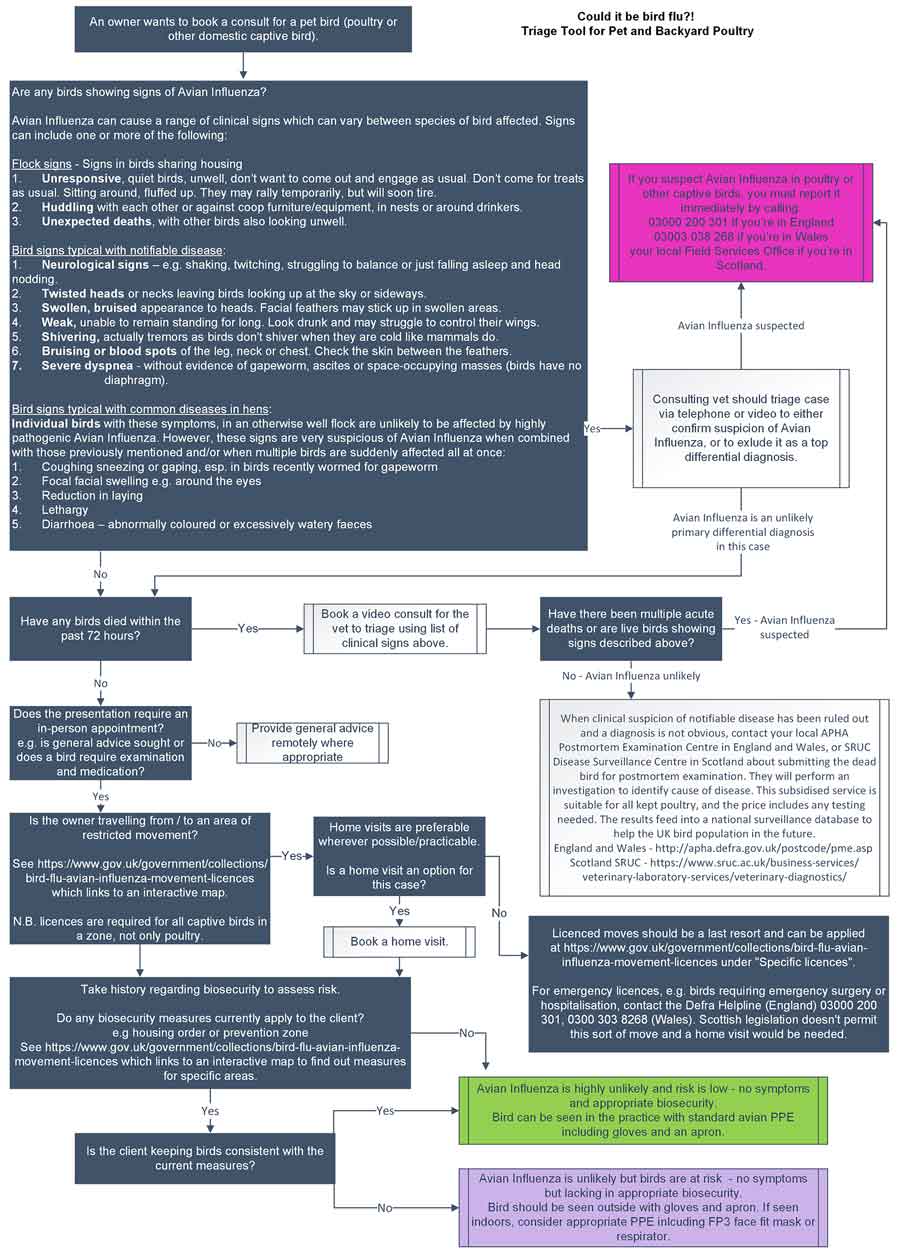

Ensure vets have access to the BSAVA Companion article “How to… manage respiratory diseases of backyard hens” (Kodilinye-Sims, 2021) and the poultry triage tool on all computer desktops for easy access during consults.

During a housing order, ensure vets have access to the housing order summary to be able to advise clients (GOV.UK, 2022d).

Ask owners to bring a second, healthy bird for company to reduce the stress and provide the vet with a normal comparison.

On arrival to appointments, invite owners to scan a QR code for the BVPA avian influenza page to read about biosecurity while they wait.

Particularly during a housing order, ask owners to bring a short (20 second), good-quality video tour of their coop to their appointment. Vets can use these videos to triage biosecurity.

The practice poultry welfare officer can discuss the video with the owner to help them comply with the additional regulations. This is good practice at any time of year to provide advice on husbandry and management.

- This article was updated on 11 May 2023 with the triage tool.