8 Mar 2022

Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome: an overview

Moira Watkins BVMS, MRCVS discusses disease grading, management options and postoperative care for this disease, which can appear in certain dog breeds growing in popularity in the UK.

One of the conformational issues by the explosion of pet ownership throughout the COVID-19 pandemic is the rising number of cases of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS), which is a condition prevalent in some of the UK’s most popular dog breeds.

The challenge for the veterinary profession is not only to identify and treat affected individuals from within the population of dogs presenting to primary care clinicians, using surgical and non-surgical options, but also to educate clients on how to recognise clinical signs of the disease as early as possible.

Research from the Pet Food Manufacturers’ Association report an estimated 3.2 million UK households have acquired a pet since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (https://bit.ly/3FF2CeH).

The Kennel Club registrations for bulldogs and French bulldogs from the first half of 2021 have increased by more than 1,000 and 5,000 respectively when compared to the same time period in 2020.

Addressing the conformational issues of this exploding population takes time, which has led to an increase in the need for surgical intervention – particularly to the upper airway.

At Willows Veterinary Centre and Referral Service, the number of upper airway surgeries performed has increased by 70% since 2015, and almost 300% since 2011.

In 2018, a study by the University of Cambridge reported approximately 50% of pugs and 45% of French bulldogs had clinically significant signs of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS), with one in eight requiring immediate veterinary attention for severe life-threatening disease 1.

However, it is suspected that actual disease prevalence is higher.

With almost 60% of owners accepting their brachycephalic dog’s breathing signs as normal2, many will not seek veterinary advice (Figure 1). The challenge for the veterinary profession is to identify affected individuals from within the population of dogs presenting to primary care clinicians.

The high threshold for owners for respiratory noise and effort, and the benefit from early surgical intervention in appropriate cases, results in the need for evaluation of the airway in situations where this is not always the primary reason for their visit to the clinic.

Diagnosis

A relatively accurate diagnosis can be made from the dog’s clinical history and a full clinical examination.

Dogs suffering from BOAS may present with noisy, laboured breathing; dyspnoea; exercise intolerance; inability to thermoregulate; sleep apnoea; gastrointestinal signs; cyanosis; collapse; and death1-4.

During examination, auscultation of the upper airway may reveal a stertor (a low-pitched or snoring noise) or a stridor (a higher pitched or audible wheezing noise).

Differentiating these breathing noises may assist with localisation of the obstruction, with presence of stertor associated with the nasopharynx or pharynx, and stridor with the larynx or nasal planum1, 2.

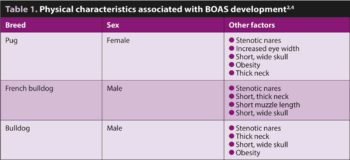

Moderate to severe nostril stenosis is a key predictor for BOAS in pugs, French bulldogs and bulldogs, but should not be over-interpreted if other aspects of the history and clinical examination do not suggest clinically relevant BOAS3,4. Table 1 highlights the other physical characteristics associated with BOAS development in these breeds. Presence of macroglossia, hypertrophic pharyngeal folds, hypertrophic tonsils, abnormal nasopharyngeal turbinates or tracheal hypoplasia may also exacerbate clinical signs.

Further investigation may include blood gas analysis, diagnostic imaging and assessment of the pharynx, larynx and nares under general anaesthesia3.

Secondary changes include eversion of the laryngeal saccules followed by collapse of the arytenoid cartilages, which has been shown to have a poor prognosis2-5.

Assessment of whether a dog is affected by BOAS requires consideration of the owner’s description of how it copes at home, when sleeping and on walks, in addition to listening for the aforementioned noises.

Evaluation for signs of secondary laryngeal collapse under anaesthesia is useful, but obviously not possible in the early stages of assessment of most cases.

The gold standard for objectively assessing our patients for upper airway obstruction is whole body barometric plethysmography (WBBP). This is a non-invasive respiratory test giving numerical or graphic information regarding a dog’s airflow1, 5.

However, WBBP is time-consuming and requires significant expertise, as well as specialised equipment.

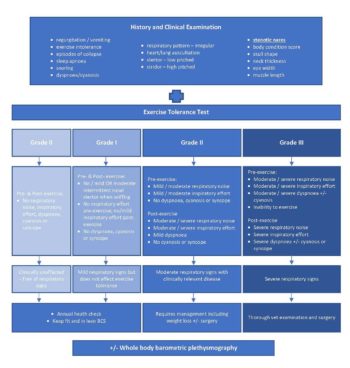

So, how do we obtain repeatable and semi-objective data without the use of specialist equipment? The University of Cambridge Respiratory Function Grading scheme aids clinicians in the management of individual patients based on syndrome severity.

Respiratory noise, inspiratory effort and episodes of dyspnoea, cyanosis or syncope are recorded before and after a three-minute trot aimed at stressing the upper airway. The airway is auscultated to detect the presence of stertor and/or stridor.

Clinical examination after this three-minute trot test has a 93% sensitivity for diagnosing BOAS, which is similar to that of WBBP at 94%1, 6.

Unaffected or mildly affected dogs (grade 0 or I out of III) usually require monitoring only. Grade II dogs have moderate respiratory signs, so need active management such as weight loss, but surgery may not be necessary.

Several options for management can be discussed with clients following BOAS grading. Non-surgical management – including weight loss, improved fitness and maintenance of a lean body condition score (4/9) – is vital (especially if dogs are overweight) and may reduce the BOAS severity in dogs with mild disease1, 3.

Managing gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting and gastroesophageal reflux, gradually increasing fitness, preventing overheating, minimising stress and using a harness rather than collar are also likely to result in clinical improvement3. In cases with acute decompensation, sedation, cooling and supplemental oxygen can be used3.

Surgery

BOAS is a progressive disease so early treatment when clinical signs first appear reduces the risk of secondary changes. However, “prophylactic” surgery before the onset of clinical signs is not recommended5, 7.

About 40% of dogs become BOAS non-affected following surgery, with marked improvement in airway function1.

However, more severe cases may require further surgical intervention or permanent tracheostomy. Surgery may include staphylectomy (posterior soft palate resection), palatoplasty (soft palate shortening and thinning), tonsillectomy, laryngeal ventriculectomy, alar cartilage resection, and laser assisted or conventional turbinectomy3, 5.

Partial cuneiformectomy and alar fold resection (vestibuloplasty) represent further evolution of multilevel surgery, and these changes are thought to have contributed to improved efficacy of conventional multilevel surgery5. Surgery can be performed in first opinion or referral practice, and despite the suitability of some cases for early discharge, it is essential that postoperative care and monitoring is available for those cases that require intensive postoperative management.

Postoperative complications have been reported in 6.5% to 26.2% of dogs. These include upper airway obstruction, dyspnoea, vomiting, regurgitation, wound dehiscence, pharyngeal inflammation and oedema, aspiration pneumonia and coughing8. Poor response to surgery has been linked to age at presentation of clinical signs, presence of laryngeal collapse and being in a slim body condition score when presenting with clinical signs (suggesting the airway disease is likely to be more severe)1. The mortality rate for BOAS correction is 0% to 3.3%3, 8.

Postoperative management

Postoperative management techniques can be considered to mitigate the risks of surgery and anaesthesia in these cases. Options include:

Oxygen supplementation/tracheostomy

Dogs should remain intubated for as long as is tolerated and kept in sternal recumbency with the head raised to reduce the risk of aspiration if regurgitation occurs3. A vet wrap roll or mouth gag can then be used with the tongue pulled out to aid oxygen supplementation.

Progressive dyspnoea following extubation can be managed by sedation, oxygen administration (via intranasal catheter, flow-by or nasal prongs), active cooling, administration of anti-inflammatory drugs and epinephrine nebulisation of upper airways.

One of the most common postoperative complications is upper airway obstruction with 1.5% to 10% of dogs requiring temporary tracheostomy tube (TTT) placement following multilevel airway surgery for BOAS3, 9.

However, a 95% complication rate has been reported with TTT, so placement should be considered a last resort. Suctioning of the TTT is performed as needed to clear secretions or the tube is removed, cleaned and replaced if obstruction is still suspected or the tube has dislodged9.

Postoperative inflammation

During the surgery, a crushed ice pack placed in the oropharyngeal region can reduce soft tissue swelling.

Dexamethasone (if not contraindicated) is often given before surgery with a dose of 0.05mg/kg to 0.2mg/kg IV recommended. A single repeat dexamethasone dose or 0.5mg/kg to 1.0mg/kg oral prednisolone every eight hours may be given for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively.8, 10

Analgesia

Opioids have been associated with increased risk of vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux and regurgitation in dogs undergoing

general anaesthesia10.

Methadone (0.1 mg/kg to 0.3mg/kg) or buprenorphine (0.02mg/kg) can be given if required, with multimodal analgesia used to minimise the dose needed. Paracetamol is often given routinely at 10mg/kg every 8 to 12 hours. Alternatively, a non-steroidal may be used – provided blood pressure has been stable throughout the anaesthetic, no steroid treatment has been given and no other contraindications exist.

A maxillary nerve block may be performed using bupivacaine and has a reported duration of three to six hours11.

Other analgesics used may include ketamine, lidocaine and fentanyl, but are rarely needed.

Sedation

Dogs can become unsettled on recovery and during subsequent hospitalisation. The following sedatives can be used if needed:

- Acepromazine at 5µg/kg to 10µg/kg IV every three to six hours3, 11.

- Medetomidine at 1µg/kg to 3µg/kg IV up to every hour if needed with or without CRI of 1µg/kg/hour to 2µg/kg/hour11.

- Dexmedetomidine at 0.5µg/kg to 1µg/kg IV up to every hour if needed with or without CRI of 0.5µg/kg/hour to 1µg/kg/hour11.

- Trazodone at 4mg/kg if the dog is able to take medication orally; this can be given twice daily and the dose titrated up to 10mg/kg to 12mg/kg if needed12.

Nebulisation

Nebulisation with 0.3mg to 1mg epinephrine diluted in 2ml to 5ml sterile saline every 6 hours for 24 hours is effective at reducing upper respiratory tract oedema due to vasoconstriction, and also results in dose-dependent bronchodilation14.

Regurgitation management

It is important to find out if the dog has a history of gagging, hypersalivation, vomiting or regurgitation before surgery.

Gastroesophageal reflux is more common in brachycephalic breeds due to increased intrathoracic pressure, chronic aerophagia and a higher prevalence of hiatal hernias13.

Dogs at risk should be treated with 1mg/kg omeprazole twice daily for one to two weeks before surgery with concurrent metoclopramide if regurgitation persists7.

Consideration can be given to low-fat diets, or a hydrolysed diet that is also low in fat, to speed up gastric emptying and try to minimise any contribution from dietary intolerance.

Instigation of treatment of concurrent inflammatory bowel disease can be beneficial in some cases.

If the dog regurgitates during the surgery or on recovery, suction can be used to empty the oesophagus, with the endotracheal

tube cuffed14.

Preoperative and postoperative medications available for management include:

- Omeprazole at 1mg/kg twice daily13.

- Metoclopramide at 0.25-0.5mg/kg twice daily or as a CRI at 0.5mg/kg/24 hours (doses of 1-2mg/kg/hr have been reported,10 but the side effects were not recorded so the author prefers to use a more conservative dose).

- Maropitant used at 1mg/kg to alleviate postoperative nausea13.

- Ondansetron at 0.5mg/kg IV followed by a 0.5mg/kg/hr infusion for six hours or 0.5-1mg/kg orally every 12 to 24 hours12.

- A 4.2% bicarbonate solution can be instilled into the oesophagus if the pH of the regurgitated content is

below four15.

Ocular care

Brachycephalic ocular conformation, a reduction in corneal sensation and poor tear film production, predispose these dogs to corneal trauma.

Medications used and an inability to blink during the general anaesthetic further increase this risk. Therefore, regular ocular lubrication every 4 hours should continue for 24 hours following surgery, and dogs monitored for signs of blepharospasm, epiphora or ocular discomfort14, 16.

Feeding

Once the dog has fully recovered, small balls of soft food can be hand-fed.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that responsible breeding is the key to maintaining and improving the welfare of brachycephalic breeds.

However, as demand for puppies soars, this is often not a priority for breeders, with The Kennel Club’s #BePuppywise campaign finding almost 20% of new owners spend less than two hours researching their new puppy and where they will get it from (https://bit.ly/3KwYvVE).

Therefore, increasing public awareness of BOAS and responsible puppy buying is essential. Further client education is also needed to help owners recognise clinical signs of BOAS as early as possible so management options can be discussed and surgery performed if needed before severe disease develops.

If surgical treatment is performed, intensive postoperative care will be required to give best outcomes, although owners should be made aware of potential risks and the need for continued future management.

- The author would like to thank Chris Shales, head of soft tissue surgery at Willows Veterinary Centre and Referral Service, Solihull for his support and advice in preparing this article.

- Some drugs referenced in this article are used under the cascade.

Latest news

Related clinical resources

Diagnosing arthritis in cats

Clinical Assist