27 Aug 2021

Challenges in Giardia treatment and control

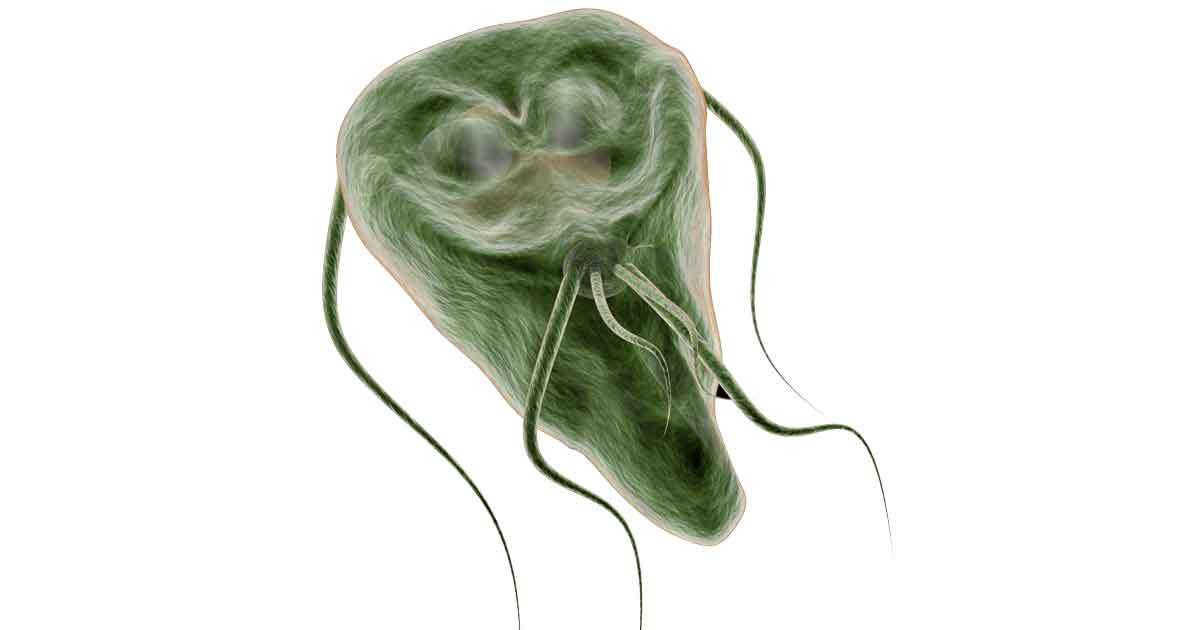

Giardia protozoan 3D model. Image: fotovapl / Adobe Stock

Infections with Giardia duodenalis are common in cats and dogs throughout Europe, with many pets acting as subclinical carriers. This, alongside zoonotic risk and potential for reinfection, makes decisions about when and how to treat Giardia difficult. This article considers the challenges of treating and managing Giardia infections in cats and dogs.

Giardia duodenalis (also known as Giardia intestinalis) is a flagellate protozoan that inhabits the intestines of a variety of domestic and wild animals. Infection can be subclinical and prevalence of infection high (Bouzid et al, 2015). This can make it difficult to establish the significance of infection found in patients with diarrhoea.

With possible Giardia resistance developing to chemotherapeutic agents (Lalle and Hanevik, 2018), whether to treat infected patients, with what agents and how to prevent reinfection all require careful consideration.

Life cycle and zoonotic risk

The life cycle of all Giardia species is direct with flagellate trophozoites dividing by binary fission in the small intestine and intermittently forming infective cysts, which are passed in the faeces.

Transmission occurs by the faecal-oral route with environmental contamination with cysts. Cysts can be long lived in the environment – especially in cool, damp conditions. Many species of Giardia are species-specific, but G duodenalis can infect a wide variety of mammals including humans, cats and dogs. Studies across Europe have found high prevalence in both cats and dogs, including in the UK.

G duodenalis is commonly split into eight subgroups or assemblages, with each assemblage being species-specific in the immune-competent host. This means that dogs are unlikely to infect cats and vice versa if living together in households, and pose very little zoonotic risk. The exception is if people are already infected from other sources.

Infection in humans is with assemblages A and B, which can potentially also infect cats and dogs if they are exposed to environmental contamination from human infection (Caccio et al, 2005). This means that human infection can be cycled through pets, allowing transmission to other people.

Although the infected person may exercise strict hygiene around food and communal items, it would still be easy for pets in the household to become infected and then pass on the disease to other people.

People infected with Giardia who work with domestic animals also pose a high risk of passing on infection. Animals infected by the person may then remain a reservoir of infection and pose a risk to other people. As a result, veterinary professionals infected with the parasite should be isolated from pets at work until the infection has been cleared.

Infected people should also maintain strict hygiene with their own pets, and avoid contact with other cats and dogs if possible until infection has been resolved.

Clinical signs

No pathognomonic clinical signs are associated with Giardia infection and many cases are subclinical.

The most common sign is chronic, sometimes intermittent small bowel diarrhoea. This can be mucoid, foul smelling and accompanied by flatulence. Lethargy and weight loss may also develop in the face of a good appetite. Less commonly large bowel involvement with tenesmus, and the presence of mucous and fresh blood in the faeces, may occur.

Clinical disease is most likely to occur in young animals and in the immune-suppressed. The clinical picture can also be further complicated by concurrent gastrointestinal disease and infection.

Puppies and kittens with diarrhoea will often have mixed infections of Giardia, Campylobacter and Cystoisospora. The prognosis is good in most clinical cases, but young, debilitated, geriatric, immunocompromised animals are more likely to be severely or chronically affected. The non-specific nature of the clinical signs of giardiosis means that Giardia should be considered as a differential in the investigation of all diarrhoea cases in cats and dogs.

Diagnosis

The following methods are all useful in the diagnosis of Giardia species infection.

Treatment

Treatment is not advised for subclinical carriers of Giardia as infection is common, zoonotic risk is very low and potential exists for drug resistance to develop.

The exception is when the aim of treatment is to eliminate the parasite from multi-pet households, or breeding or kennel establishments.

In clinical cases, a number of different drugs have been shown to have some efficacy.

Control in breeding establishments, kennels and multi-pet households

The potential for clinical outbreaks makes the control and prevention of spread of Giardia very important in catteries, kennels, breeding establishments and multi-pet households. A number of steps are required to achieve this:

- Wash infected and in-contact pets – with shampoo, particularly around the perineum to remove faecal contamination and cysts from the coat.

- Move pets to clean holding areas – to allow previously inhabited areas to be disinfected.

- Disinfect kennelled areas and runs the animals came from with a quaternary ammonium compound – to reduce environmental contamination with cysts, these areas should be cleaned, dried and disinfected with chlorine bleach, chloroxylenol or quaternary ammonium compounds. The areas should then be allowed to dry for 48 hours before reintroducing pets. Bedding should be washed at 60°C or above.

- Screen animals – to identify those shedding cysts.

- Treat clinical cases – to eliminate or significantly reduce shedding.

Discussions should be had with the client before elimination strategies are initiated. Success requires good compliance, areas where pets can be isolated and environments where large areas can be cleaned/hot washed with disinfectants. This may not be practical in some household situations and a labour-intensive prolonged elimination programme may be something some pet owners to not want to undertake.

Without these steps, however, clinical infections in multi-pet households are likely to be recurrent – especially in those with large numbers of young or sick animals.

Conclusions

Giardia infections are common and can lead to significant gastrointestinal signs in affected pets. Treatment with chemotherapeutic agents is useful for reducing clinical signs, but has limitations.

Parasiticides will have minimal impact on Giardia cyst shedding and a risk exists of drug resistance developing. As a result, little justification exists in treating subclinical carriers, other than as part of an organised programme to eliminate infection from groups of animals where repeated clinical infections are occurring.

Whether clinical infection is being controlled in an individual pet or a group, hygiene plays a key role in reducing environmental contamination and subsequent infection levels. Consideration of Giardia as a differential in diarrhoea cases and early diagnosis using a combination of techniques will help to control outbreaks and improve treatment outcomes.

- This article was amended to correct the print version, which originally said metronidazole was unlicensed.