17 Jun 2019

Companion animal analgesia

Karen Walsh looks at uses and latest developments in analgesics, as well as types available in canine and feline patients.

Image: © Tyler Olson / Adobe Stock

If a procedure is elective, then it is an important part of the case preparation to have an analgesic plan in place for the perioperative and postoperative phases. Thinking about the pain the patient is likely to experience due to the injury or surgery will help the clinician to target the analgesic therapy.

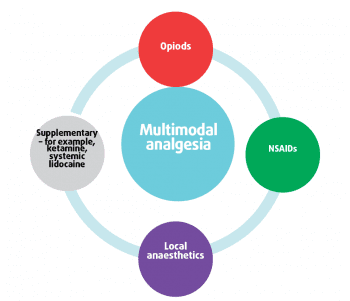

Using a multimodal approach (Figure 1), using drugs from more than one group of analgesics will help to reduce the dose of each individual agent that is used and potentially improve the level of analgesia (Murrell, 2014).

An integral part of providing analgesia is monitoring the level of pain and comfort of a patient. Scoring systems validated for both dogs and cats for acute pain exist. No validated scoring systems exist for dogs and cats for chronic pain assessment; we rely on quality of life information for this group of patients. Some scoring systems are available for these including the brief pain inventory and from NewMetrica.

Constant rate infusions

A constant rate infusion (CRI) is useful if the clinician wants to deliver a short-acting drug over a long period of time or it is desirable to have a consistent plasma level of drug. The more consistent plasma levels will mean there is less chance of breakthrough pain when the blood levels fall.

Fentanyl is a short-acting drug that is often administered as a CRI to help improve analgesia and reduce the dose requirements of other anaesthetic agents. Longer-acting opioids, such as methadone and ketamine, can also be used as a CRI, but as they have longer half-lives a steady state may take longer to achieve.

Patients receiving analgesia in this way will require close monitoring to prevent over or underdosing. Delivery is dependent on a patent IV access, so cannula care is an important part of the treatment.

Regional anaesthesia

These can take the form of specific perineural blocks – for example, sciatic, femoral, injections into joints, and extradural (epidural) and spinal administration. Although some of these can be more technically challenging, they can provide profound analgesia during the surgical and post-surgical phases. Application of drugs may be administered as a “one-off” injection, or can be repeatedly or continuously administered if a delivery device, such as an epidural catheter, is placed.

Classically, the drugs associated with these techniques are local anaesthetics, but other drugs, such as opioids or α2 agonists, can be administered in combination with local anaesthetics or in place of them.

Oral transmucosal

Oral transmucosal (OTM) relies on the transfer of drug across the mucous membranes, rather than absorption via the gastrointestinal system. This has been used as an off-licence administration of buprenorphine.

A preparation of dexmedetomidine exists that has been licensed for OTM use in dogs for anxiolysis.

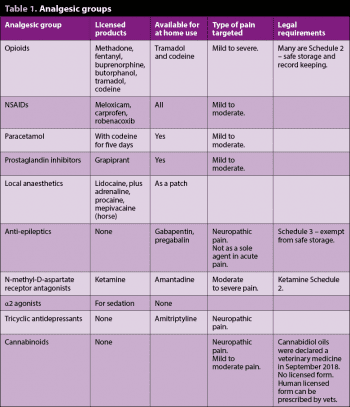

Types of analgesics (Table 1)

Opioids

The group of drugs derived from morphine is still the gold standard for analgesia in companion animals for acute pain, and some instances exist where these drugs may be indicated in a chronic pain setting. As with all choices of medicines, we should follow the cascade and use the product licensed in the species and for that purpose.

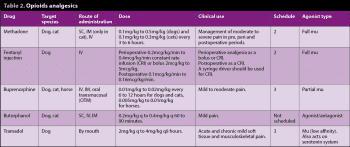

The author prefers a full agonist opioid when administering analgesia in the preoperative and perioperative period as it is easier to administer additional opioid analgesia. Several licensed products are available for use (Table 2).

Methadone is one of the most commonly used full agonist opioids and can be combined with sedatives in the pre-anaesthetic medication to improve sedation and provide analgesia during surgery. It is a full mu agonist that allows a bit more flexibility when additional analgesia is required.

Buprenorphine is a partial mu agonist that is licensed for use in dogs and cats for postoperative pain. It is effective for mild to moderate levels of pain. A long-acting buprenorphine is licensed in the US for cats that lasts 24 to 28 hours and can be administered for up to three days (Bradbrook and Clark, 2018). It is not available in the UK.

Oral administration

The advantage of oral and OTM preparations of opioids is that pain relief can be administered at home or in a less invasive way in the hospital situation. Prescriptions for controlled drugs are valid for 28 days from the date of signing, and the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee advises a supply of no longer than 30 days. Longer periods of supply should be because of a clinical need.

Tramadol

Tramadol has been licensed in the UK via the IV and oral route. It has several modes of action: mu receptor, serotonin system, α2 effects, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonism and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV) receptor antagonist activity (Bradbrook and Clark, 2018).

Tramadol needs to be metabolised to O-desmethyltramadol for its primary effect; however, some dogs may have lower or no metabolism, so variable plasma levels can exist. This can make tramadol an unpredictable drug for analgesia. Tramadol is metabolised via the cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway, which can be suppressed or enhanced by particular drugs.

Tramadol bioavailability was increased when it was administered in combination with cimetidine or ketoconazole (Kukanich et al, 2017), therefore care should be taken in the clinical setting when patients are on drugs that upregulate CYP activity. It has also been reported tramadol excretion is significantly prolonged in middle-aged dogs (Itami et al, 2016).

The efficacy of tramadol with regards to analgesia appears to be variable and it is licensed in the dog for “acute and chronic mild soft tissue and musculoskeletal pain”. When reviewing the literature, differences in the reported analgesic activity exist. It does appear to decrease the isoflurane and sevoflurane requirements in dogs in experimental studies, and evidence exists of efficacy in soft tissue procedures, such as tumour removal, but other studies in orthopaedic and ophthalmic patients did not find it to be a useful addition to the postoperative analgesia protocol (Benitez et al, 2015; Davila et al, 2013; Delgado et al, 2014).

Side effects of tramadol are similar to many opioids, such as sedation, nausea, vomiting and, potentially, constipation. A small risk exists that it may potentiate seizures and it is specified as a contraindication in epileptic patients. An interaction also exists with tricyclic anti-depressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Tapentadol

Is an unlicensed mu opioid drug and also works on the noradrenaline system. It is like tramadol and is more useful in chronic pain.

OTM route

OTM drug bioavailability is dependent on the molecule size, the protein affinity and lipophilicity from the point of the drug. Other factors include the pH of the saliva, the pKa of the drug and carrier vehicle. Buprenorphine is the most common opioid administered via this route.

Cats have a higher bioavailability of buprenorphine compared to dogs as their saliva is more alkaline. Bioavailability via the OTM route for buprenorphine in the cat may be up to 100%. It can be used as an alternative to repeat injections in the hospital setting or dispensed for at home use. Some of the specials manufacturers have developed higher concentration oral solutions (0.2mg/ml and 0.8mg/ml) for sublingual use.

Local anaesthetics

Local anaesthetics have been classically used to prevent nociceptive messages travelling up the sensory nerves to the spinal cord and are, therefore, one of the most complete forms of analgesia. They have become more commonly used in companion animal analgesia when used to perform nerve blocks – for example, sciatic and femoral. They can also be used to produce regional analgesia, such as with epidural or spinal injections.

Analgesia can be produced by local anaesthesia when administering lidocaine IV as a CRI. The correct equipment is required to administer the drug accurately and IV access needs to be maintained. Lidocaine CRI is better administered in combination with other drugs, such as methadone or ketamine, to achieve multimodal analgesia.

NMDA receptor antagonists

Ketamine is the most commonly used NMDA receptor antagonist in clinical practice. The NMDA receptor is closely associated with the sensitisation pathway that leads to chronic pain. Incorporating ketamine into the perioperative anaesthetic protocol may help to reduce overall opioid requirements and potentially reduce the likelihood of sensitisation. It can be combined with other agents to reduce side effects and enhance effect. Ketamine can be used as a bolus or a CRI. The analgesic action occurs at sub-anaesthetic doses and we are using lower and lower doses for analgesia.

Ketamine is a controlled drug that needs to be safely stored and its use recorded in a controlled drugs register.

Amantadine and memantine are oral NMDA receptor antagonists that can be used for chronic or neuropathic pain. It is not licensed for veterinary species and the medication can be difficult to split to provide the correct dose, although some specials manufacturers will supply lower mg tablets. The effect of these drugs can be prolonged in patients in renal failure.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are some of the most commonly prescribed drugs for humans and veterinary patients. They are particularly effective for postoperative pain and osteoarthritic pain. A number of anti-inflammatories licensed for use in dogs and cats exist. Which drug to choose will depend on patient factors, ease of use and licensing. Complications associated with NSAIDs are renal and gastrointestinal, the most common reported are related to gastrointestinal effects (Kukanich et al, 2012). Acute kidney injury (AKI) from NSAIDs is more likely to occur in patients that already have impaired renal function. Other factors that may increase the risk of AKI are hypotension and medication, which may change renal haemodynamics.

Prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 antagonist

Grapiprant is a specific antagonist of the prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 (EP4). It binds to the receptor with high affinity and has shown to be extremely well-tolerated in an experimental study when it was given daily for nine months to laboratory beagles at up to 15 times the therapeutic dose (Rausch-Derra et al, 2016b). It has been licensed for use in dogs to treat OA.

The proposed benefits are that this drug does not affect prostanoid production, which is important in maintaining many physiological processes including gastrointestinal integrity. A study conducted in client-owned animals found it was more effective than a placebo for the alleviation of pain in dogs with OA and that it may be better tolerated than current medication (Rausch-Derra et al, 2016a). However, much work remains to look at effectiveness compared to current treatments and its use over long periods of time. In this study, approximately 17% of patients had occasional vomiting while being treated.

α2 agonists

α2 agonists are classically used as sedatives, although they do possess analgesic properties that can be used in a multimodal analgesic protocol. It can be difficult to assess the degree of analgesia when there is significant sedation. They are unlikely to become a first line analgesic choice when considering the other analgesic groups available. Medetomidine and dexmedetomidine have been administered as CRIs to provide analgesia postoperatively.

Dexmedetomidine and medetomidine can be combined with local anaesthetics to help increase the duration of a perineural block. A meta-analysis in humans compared 32 trials involving 2,007 patients and found improved pain control and reduced morphine consumption postoperatively (Vorobeichik et al, 2017). However, they did caution there would be evidence of systemic effects, such as bradycardia and hypotension. The evidence in veterinary patients is sparse and does not appear to be supportive of this practice, but the authors did feel other doses of dexmedetomidine should be investigated (Trein et al, 2017).

Anticonvulsants

Gabapentin and pregabalin have become more commonly used as analgesics in veterinary patients in the past few years. They are both now Schedule 3 drugs, but are exempt from the requirements of safe storage. However, as these drugs can be abused it is probably good practice to keep them in a locked cupboard.

These drugs are not licensed for dogs and cats, but clinical studies exist documenting their use in these species with chronic and neuropathic pain. The major side effect with both drugs is sedation, which appears to decrease with time. The drugs appear to be excreted through the kidney, so adequate renal function is important to prevent accumulation.

In the human literature, it is stated the drug should be withdrawn gradually as it may be associated with status epilepticus – even in patients that have not been documented as epileptic. This has not been documented in dogs and cats, but should be kept in mind and it may be safer to withdraw them over about a week. Long-term use appears to be well-tolerated.

The choice of which drug to use may, in the end, be governed by price as pregabalin is still on patent and is significantly more expensive than the two available formulations of gabapentin.

Dosing may be difficult in the cat because of the size of medication as they have been developed for human use. It is possible to have it reformulated to more appropriate strength capsules, but it will affect cost. Cats also often do not like the taste of gabapentin as it is bitter, so opening the capsule and sprinkling on the food is unlikely to help with compliance.

Acute pain

A few studies exist looking at the effects of gabapentin in the perioperative period in dogs and none in cats. The results in dogs were variable with a positive effect on morphine requirements in patients undergoing mastectomy (Crociolli et al, 2015), but minimal or no effect in patients that underwent hemilaminectomy (Aghighi et al, 2012) and limb amputation (Wagner et al, 2010). The discrepancy between these studies indicates further work is required, and there may be benefits in different surgical types and at different doses and dosing intervals. Due to the pharmacokinetics in dogs, it has been suggested a dose of at least 10mg/kg every eight hours should be prescribed to maintain a therapeutic blood level similar to that which will result in analgesia in humans (KuKanich, 2013).

Chronic pain

Gabapentin has been recommended for chronic use in dogs and cats for neuropathic pain, and as an adjunct therapy for OA.

A study by Guedes et al (2018), found there was an improvement in owner-identified impaired activity, but a decrease in activity levels at a dose of 10mg/kg twice daily for two weeks. Sedation was the most common adverse effect. Although the author will use gabapentin as a second line treatment for OA, little evidence exists to support this in dogs.

Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids have been of interest to medical pain specialists for some time and it is likely as their profile increases that vets will be asked about their possible use in companion animals for pain relief.

Preclinical studies in a wide variety of pain models have demonstrated these drugs may have a dissociative effect on the pain pathways. Some synthetic cannabinoids have also been licensed for specific uses in humans. The two active cannabinoids with the strongest evidence for analgesia are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC also has psychoactive effects. As with other types of analgesics, it is important to look at the type of pain being treated, as a metanalysis in human medicine did not find significant evidence to advocate the use of cannabinoids in neuropathic pain. However, the use of these drugs needs to be balanced against the possible side effects, such as psychosis/behavioural changes. Although interest in their use in our species exists, there are, as yet, no licensed products available and clinical dose response studies have not been published. Much of the published literature is in relation to inadvertent overdose, rather than clinical use.

Since September 2018, CBD products have been classed as veterinary medicines, meaning it is illegal to administer an unauthorised product containing CBD without a veterinary prescription. It is possible for vets to prescribe a human CBD product under the provisions of the cascade (VMD, 2018).

Latest news