6 Jun 2023

Cytology findings from a leg skin mass in a dog

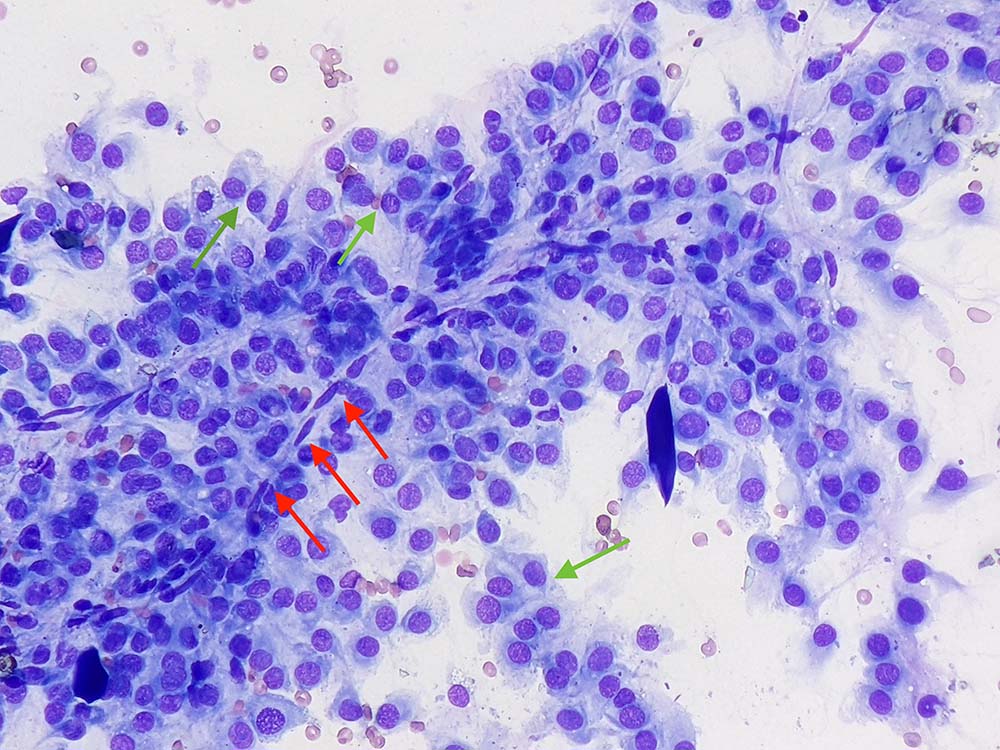

Figure 1. Left hindleg skin mass in a dog (Wright-Giemsa 50×).

A 10-year-old male, neutered German Shepherd dog presented to the referring vet for presence of a large mass (8cm in diameter) on the right elbow.

Clinical examination was unremarkable, and thoracic radiographs and abdominal ultrasound did not show significant changes that might suggest neoplasia. A fine-needle aspirate from the elbow mass was collected and submitted to an external laboratory for analysis.

The aspirate (Figure 1) contains highly cellular areas with adequate preservation. The background is clear, with low numbers of red blood cells.

A main population of round to slightly spindloid cells is observed (green arrows), often forming poorly cohesive groups, sometimes associated with capillaries (red arrows). Cells have moderate amounts of lightly basophilic cytoplasm – often wispy and forming a tail – which is a feature suggestive of mesenchymal origin. Rarely, they also contain intracytoplasmic, clear vacuoles. Nuclei are round to oval, with granular chromatin, and are small nucleoli.

Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are mild to moderate, and a few binucleated elements can be noted. Rare leukocytes – likely blood derived – are also seen.

Diagnosis

These cytological findings suggested a diagnosis of mesenchymal neoplasia, and a perivascular wall tumour was considered very likely.

Follow-up

An excisional biopsy with wide margins was performed and submitted for histopathology, which confirmed the cytological diagnosis.

At 12 months from surgery, the dog was alive and free of disease.

Insight

Perivascular wall tumours (formerly known as haemangiopericytoma) are relatively common skin neoplasms, affecting canine species – in particular, middle-aged or older subjects. Studies have showed this is not a single neoplasm, but it represents a spectrum of tumours arising from various cells of the perivascular wall and the adventitia (for example, pericytes and myopericytes), including haemagiopericytoma, myopericytoma, angioleiomyoma, angiomyofibroblastomas and angiofibromas.

They often appear as solitary lesions, with predilection for the limbs and joints. They have variable gross appearance and sometimes may be confused for lipoma, given their rubbery to fatty appearance.

Treatment involves wide surgical excision (when possible) and is often curative. Local recurrence is not uncommon, and metastatic risk is low. This group of tumours has quite characteristic morphological features that can be appreciated on cytology (for example, multinucleated crown cells with nuclei aligned at the periphery, binucleated cells also known as insect eye cells or a perivascular pattern, as seen in this case).

However, other types of soft tissue sarcomas may appear similar, making the use of this umbrella term preferable.

In the presence of concurrent inflammation, attention must also be paid to differentiate neoplastic mesenchymal cells from reactive fibroblasts. This is often not possible on cytopathology, requiring a solid biopsy and histopathological examination.

Studies have shown that perivascular wall tumours (PWTs) may represent a less aggressive form of soft tissue sarcomas, meaning a more conservative surgery could be applied to PWTs arising in the extremities where a 3cm lateral margin cannot be achieved.

Although PWTs seem to display more favourable behaviour, the definition of specific prognostic variables may aid clinicians in the selection of dogs requiring adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of local recurrence.

The two main prognostic variables identified for PWTs are tumour size and the histological infiltration of the underlying muscular layer. Specifically, each centimetre of increase in tumour size has been associated with a greater risk of relapse and a size larger than 5cm, or involvement of muscular layer increases the risk of recurrence sevenfold and eightfold, respectively.