1 Feb 2016

Dental imaging options in horses: part 1 – radiography

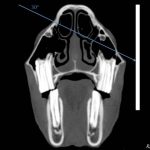

Figure 1. For a lateral view of the head, the x-ray beam is centred just dorsal to the rostral facial crest.

Thorough oral examination will usually allow diagnosis of many dental conditions, such as periodontal disease with associated diastemata, exposure of pulps, fractured teeth and infundibular caries.

All these conditions can be involved in apical infections, but further examination using one or more forms of diagnostic imaging is usually mandatory before a tooth is treated – or, more commonly, condemned to extraction. Suspected apical infection is by far the most common indication for advanced imaging in the equine dental patient.

Radiographic examination is the mainstay in dental disease imaging; however, its usefulness depends on the position of the suspected tooth within the head and the chronicity of the changes identified.

Radiographic techniques

Most generators and x-ray plates are suitable to image the equine head. Using the largest plate available is recommended, as this allows examination of the entire dental arcade and surrounding tissues. Sedation is regularly indicated to facilitate safe and accurate image acquisition.

Once the horse is suitably sedated, the head is stabilised by resting it on a headstand or stool, which reduces movement artefacts caused by sedation-induced swaying and a radiolucent rope head collar is used to restrain the horse. All associated personnel holding the horse or the x-ray plates, and the radiographer, should wear gowns, gloves, thyroid protectors and dosimeters at all times.

The lateral view of the head is useful for assessing the sinuses and is essential in the diagnosis of dental sinusitis cases. Superimposition of both sides of the head is the major drawback of this view. Due to this, localisation of lesions to either the right or left side of the head is complicated.

The plate is positioned vertically, adjacent to the side of the face, and parallel to the long axis of the head. The x-ray beam is centred just dorsal to the rostral facial crest (Figure 1) and aimed perpendicular to the long axis of the head and the plate (Figure 2). Collimation should be employed to limit scatter, but the entire maxillary arcade and sinuses should be included.

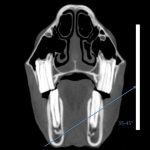

The latero-30°-dorso-lateroventral oblique view reduces superimposition and, therefore, enables identification of structures within the sinuses. It also provides the clearest radiographic view of the maxillary cheek teeth apices. Fluid lines within the sinuses are not visible on these projections; instead, fluid in the sinuses appears as an area of uniform increased radiopacity.

The plate is positioned vertically against the head, adjacent to the side of interest, and parallel to the long axis of the head. The beam is angled 30° ventrally from horizontal and centred just dorsal to the rostral aspect of the facial crest (Figure 3).

The beam should be aimed perpendicular to the plate, preventing distortion of the apices by rostrocaudal angulation. Collimation should be used, but inclusion of the entire maxillary cheek teeth row is mandatory. A higher exposure is generally required to image the teeth apices, compared to that used for the lateral view when the radiolucent sinuses are the areas of interest.

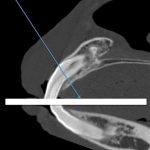

In a similar fashion, the latero-35°-45°-ventro-laterodorsal oblique view is useful in separating the left and right mandibular cheek teeth apices. The principle is similar to that of the previous view; but, instead, the beam is angled dorsally and aimed at the hemimandible of interest (Figure 4). A larger angle is often used to image the caudal cheek teeth apices or older teeth with shorter reserve crowns.

In both cases, the area of interest is usually found more dorsally in the mandible. Otherwise, the use of the shortest angle possible is recommended to prevent elongation and distortion of the apices. Collimation should ensure inclusion of the ventral mandibular cortex and the entire cheek teeth row. Once again, making sure the beam is maintained perpendicular to the plate is essential to prevent distortion of the tooth root apices by rostrocaudal angulation.

The intra-oral view is useful for assessing the incisors and canines, and involves placement of the plate or cassette into the mouth. For this reason, adequate sedation is paramount and some form of plate protection should be employed, such as a gag with radiolucent bit plates. The plate or cassette is placed into the mouth as far caudally as possible; usually the corner of the plate extends furthest into the mouth.

The x-ray beam is directed 60° to 80° from vertical and aimed dorsally for the mandibular teeth and ventrally for the maxillary teeth (Figure 5). The beam is centred on the central incisors and collimation extended to include the rostral aspect of the lips. When compared to the cheek teeth, a lower exposure is usually used.

Other views employed in dental radiography include the dorsoventral projection. This allows further examination of the sinuses, but usually provides little additional information regarding the teeth compared to the previously described views and a thorough dental examination. Open-mouth oblique views are occasionally used to assess the erupted crowns of the teeth, or to visualise fractures, wear abnormalities and diastemata.

A Gunther-type screw speculum is placed between the incisors and the x-ray beam is directed in the opposite direction to the previously described oblique views. A latero-10°-dorso-lateroventral projection is used for imaging the mandibular teeth, and a latero-15°-ventro-laterodorsal projection is used for the maxillary teeth. As with the previously described views, the primary beam is centred just dorsal to the rostral facial crest.

Normal variations

The radiographic appearance of equine dentition changes in size, shape and conformation with advancing age. Infundibula can be identified in juvenile incisors as elliptical radiodense shadows and pulp cavities are recognised as central radiolucent structures.

Very rostrally positioned canines (04s) may be superimposed over the corner incisors (03s) and the accurate examination of the reserve crown and apices may be retarded by conventional views. Some individuals, especially mares, may have small unerupted canines found subgingivally.

The wolf teeth (05s) can be identified on radiographs, with the size of their clinical and reserve crown varying greatly. Most commonly they are located on the maxillary arcade; however, mandibular wolf teeth are also possible, but rare.

Not all horses have them and some may have had them removed earlier in life.

The cheek teeth are particularly radiopaque and become more opaque with age as the teeth develop a higher proportion of dentine with maturity. The pulp horns appear as radiolucent longitudinal structures within the teeth. The periodontal ligament forms a narrow radiolucent margin between the radiodense reserve crown and radiodense rim of cortical bone known as the lamina dura (Figure 6).

The lamina dura is not always continuous in normal teeth and interpretation of its loss in diseased teeth is difficult. The developing apices of young horses have very wide radiolucent zones and, therefore, interpretation of cheek teeth radiographs in younger horses is difficult, as these regions can often resemble apical infections (Figure 7).

These regions (commonly known as eruption cysts) also tend to form mandibular swellings, which are often referred to as “three and four-year-old bumps”. As the horse matures, the reserve crown erupts further, the mandibular bone remodels and the bumps reduce in size and often disappear. Additionally, at this age the lamina dura is usually absent around the apices of the developing teeth.

With advancing age, the true roots develop with deposition of further dental tissue at the apices to form the recognisable pointed root structures. Due to differing eruption times, the juvenile horse will often have a variety of stages of apical development evident on radiographs (Figure 7).

For the same reason, the reserve crowns of the permanent dentition are varying lengths, with the 09s and 06s being the shortest. As the horse ages, the reserve crowns become shorter and cementum continues to be deposited at the apices. This obscures the roots and makes them appear more radiodense, rounded and thicker, which is often known as a “clubbed appearance” (Figure 8).

As a general rule, the apices of the two most caudal maxillary cheek teeth (10s and 11s) are located within the caudal maxillary sinus (CMS), and the caudal aspect of the 08s and 09s are in the rostral maxillary sinus (RMS; Figure 9).

The apices of the more rostral cheek teeth are usually embedded in the maxillary alveolar bone. The maxillary septum, separating the RMS and CMS into two distinct spaces, is positioned dorsal to the most caudal aspect of the 09 teeth.

Abnormalities

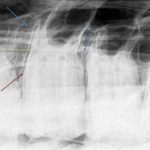

Rostral maxillary and all mandibular cheek teeth with apical infections usually have a bony swelling adjacent to the apices. This is seen on radiographs as an area of lucency surrounded by a region of sclerosis and periosteal new bone formation (Figure 10). In some cases, cutaneous draining tracts may be present and placement of a radiodense metallic probe within the tract can pinpoint the source of the tract to a specific dental apices (Figure 11).

Similarly, placement of a metallic ring around a bony swelling will offer a similar localisation (Figure 10). These changes may also be observed in the caudal upper cheek teeth and are often identified as local densities (encapsulated abscesses and granulomas) with increased radiopacity in otherwise radiolucent sinuses. Obvious fluid lines may also be present in the sinuses (Figure 12).

In less destructive, but chronic, periapical infections, reactive cementum may be deposited at the apex of the affected tooth in an attempt to help control the infection. This appears radiographically as an increase in size and blunting of the apex. If the infection progresses and becomes more destructive, the apex becomes more radiolucent as it is progressively lost and appears “clubbed” (Figure 13).

In some chronic cases, dystrophic mineralisation of the nasal conchae occurs, which can also be observed radiographically. This is often known as “coral formation” and is more commonly seen in the rostrally positioned teeth. Radiography of the caudal maxillary arcade and sinuses may reveal synonymous dome-shaped soft-tissue opacity on the floor of the maxillary sinuses dorsal to an apically infected supernumerary tooth.

Apical infections in the earlier stages are harder to diagnose, but subtle radiographic changes, such as widening of the periodontal space and focal loss and irregularities of the lamina dura, may indicate their presence. In some cases of apical infection, radiographic examination may be unremarkable and advanced imaging techniques would be warranted, such as CT, MRI or scintigraphy, which will be discussed in part two of this article.

Latest news