26 Jun

Diabetes insipidus in a dog

Victoria Brown explains steps taken in the case of a canine patient that presented with nocturia and urinary incontinence.

Figure 1. Lolan the 21-month-old, male, neutered crossbreed.

A 21-month-old, male, neutered cross-breed (Figure 1) presented to the practice having been adopted from Greece two-and-a-half weeks previously. He had been a stray and living in a foster home.

A clinical exam did not reveal any abnormalities. Lolan weighed 12.9kg and was set a target weight of 11kg. A free-flow urine sample revealed very dilute urine of 1.005.

The results for biochemistry, haematology, electrolytes and C-reactive protein were within normal limits. No evidence of polydipsia-induced hyponatraemia was noted.

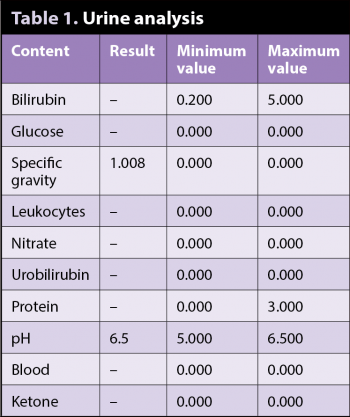

The following week, a free-flow morning urine sample was supplied, and the urine specific gravity was retested and found to be 1.008 (Table 1).

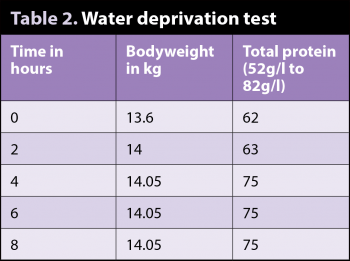

Lolan was admitted for a water deprivation test. He was placed in a small, paper bed kennel to discourage urination and was not allowed access to water (Table 2).

At the end point of the test, a free-flow urine sample was taken. The urine was almost colourless (Figure 2) and the specific gravity was 1.005.

Urine microscopy revealed the presence of casts. A symmetric dimethylarginine test showed a very slightly raised result of 15ug/dL (1μg/dL to 14μg/dL) and a basal cortisol was within normal limits – 31.2nmol/L (25nmol/L to 125nmol/L).

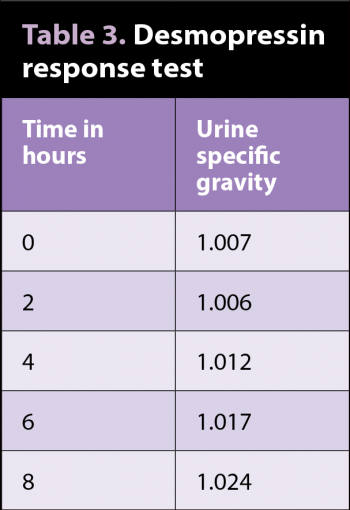

With a diagnosis of diabetes insipidus looking extremely likely, Lolan was admitted again for a desmopressin (antidiuretic hormone analogue) response test to differentiate between central diabetes insipidus (CDI) and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI). He was given 0.5ml of desmopressin IV and, again, water was withheld (Table 3).

The test was stopped when the specific gravity reached 1.024, as this was deemed to demonstrate a sufficient improvement in urine concentration to make a diagnosis of CDI.

Three days later, the owner telephoned to say, although Lolan had responded to the tablets almost immediately, and was urinating and drinking a lot less, he had developed diarrhoea. He was well in himself and showed no other symptoms. It was advised the dose of desmopressin was reduced to 0.1mg twice a day, he was transferred to a bland diet and he took a probiotic supplement for three days.

The owner telephoned two days later to report Lolan was better and his faeces had returned to normal. One month later, Lolan continues to do well on only 0.1mg desmopressin twice a day.

Discussion

Diabetes insipidus is a rare endocrine disease characterised by antidiuretic hormone (ADH) dysregulation, excessive polyuria, polydipsia, and the absence of hyperglycaemia and glucosuria. ADH is a nanopeptide synthesised in the hypothalamus.

It is then transported to and stored in the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland, which releases it into blood circulation.

The two primary functions of ADH are to retain water in the body by increasing water reabsorption in the renal nephrons, and to constrict blood vessels.

Diabetes insipidus is entirely different to diabetes mellitus and has two presentations.

- Hypothalamic-pituitary trauma.

- Post-transsphenoidal surgery for correctionof hyperadrenocorticism.

- Dorsally expanding cysts, inflammatory granuloma and lymphocytic hypophysitis.

- Congenital malformation and neoplasms, such as craniopharyngioma, pituitary chromophobe adenoma.

- Pituitary chromophobe adenocarcinoma and metastatic tumours, such as metastatic mammary carcinoma, lymphoma, malignant melanoma and pancreatic carcinoma.

The net result of central diabetes insipidus is a lack of antidiuretic hormone production, causing persistent hyposthenuria (urine specific gravities less than or equal to 1.006) and severe diuresis, and can cause severe dehydration. Given the young age of the patient and the absence of any neurological signs, a pituitary mass was deemed very unlikely.

NDI

NDI is due to nephron impairment as a result of genetic or acquired disease. This results in the renal nephrons being insensitive to ADH activity. Plasma ADH concentrations are normal or increased in animals. Primary (genetic) NDI is a rare disorder of dogs resulting from a congenital defect involving the cellular mechanisms responsible for insertion of aquaporin-2 water channels into the luminal cell membrane.

Secondary (acquired) NDI includes a variety of renal and metabolic disorders that interfere with the normal interaction between ADH and its renal tubular receptors, affecting renal tubular cell function, or decreasing the hypertonic renal medullary interstitium, resulting in a loss of the normal osmotic gradient.

In dogs with primary (genetic) NDI, clinical signs typically become apparent by the time the dog is 8 to 12 weeks of age, with symptoms of polyuria, polydipsia and urinary incontinence.

Neurological signs have been reported, dueto electrolyte disturbances or pituitary neoplasia, with depression and seizures observed in rare cases. Water consumption can often be extreme, sometimes exceeding 800ml/kg/day, with compensatory urine production exceeding50ml/kg/day.

Blood tests are usually within normal limits, but may include a polydipsia-induced hyponatraemia (not observed in this case).

Urinalysis usually shows hyposthenuria or isosthenuria, and haematuria is not regularly observed unless underlying concurrent nephropathy is present. Urine culture and sensitivity is required to eliminate underlying cystitisor pyelonephritis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is initially one of exclusion of other diseases (Panel 1), followed by water deprivation tests, ADH therapy and, if possible, central nervous imaging studies to diagnose CDI. The main diagnostic challenge is differentiating between CDI, NDI and psychogenic polydipsia. Standard haematology and biochemistry assessments are often within normal limits.

A response to synthetic ADH therapy may help distinguish nephrogenic from CDI. An increase in urine specific gravity by 50% or more, compared with pre-treatment specific gravities, supports the diagnosis of CDI – especially if urine-specific gravity exceeds 1.025. Only minimal improvement should be apparent in dogs with primary NDI. Dogs with psychogenic water consumption may exhibit a mild decline in urine output and water intake because the chronically low plasma osmolality tends to depress ADH production.

Pituitary or hypothalamic neoplasia should be considered in older dogs diagnosed with CDI.

A renal biopsy may be warranted in the older dog tentatively considered to have primary NDI.

Treatment

With hypophyseal tumours, a transsphenoidal hypophysectomy is usually recommended. In dogs that develop CDI secondary to hypophysectomy, CDI may spontaneously resolve within two to four weeks.

Prophylactic use of desmopressin at 4μg twice daily has been shown to be effective at minimising the onset of CDI.

In dogs with primary NDI, long-term therapy includes low sodium diet, unlimited water access, hydrochlorothiazide (usedto increase urine osmolality), or desmopressin tablets or nasal spray.

Management

Water should always be made available to the dog. Diabetes insipidus is usually a permanent condition, except in unusual cases where the condition was trauma-induced.

The prognosis is generally good, depending on the underlying disorder. Regular monitoring of renal functionis advisable.

- Drugs mentioned within this article are used under the cascade.

Panel 1. Differential diagnoses of chronic polyuria/polydipsia and mechanism of action

- Diabetes mellitus – osmotic diuresis

- Chronic renal disease – osmotic diuresis

- Primary renal glycosuria – osmotic diuresis

- Post-urolithiasis diuresis – osmotic diuresis, down-regulation of aquaporin-2

- Pyometra – bacterial endotoxin-induced reduced tubular sensitivity to antidiuretic hormone (ADH)

- Escherichia coli septicaemia – bacterial endotoxin-induced reduced tubular sensitivity to ADH

- Hypercalcaemia – interference with action of ADH on renal tubules

- Hepatitis – loss of medullary hypertonicity, impaired hormone metabolism

- Hyperadrenocorticism – impaired tubular response to ADH

- Hyperaldosteronism – impaired tubular response to ADH

- Pyelonephritis – bacterial endotoxin-induced reduced tubular sensitivity to ADH, damaged countercurrent mechanism

- Fanconi’s syndrome – osmotic diuresis

- Hypokalaemia – down-regulation of aquaporin-2, loss of medullary hypertonicity

- Hyponatraemia – loss of medullary hypertonicity

- Hypoadrenocorticism – loss of medullary hypertonicity

- Hyperthyroidism – loss of medullary hypertonicity

- Leptospirosis – action unknown

- Polycythaemia – action of natriuretic peptide

- Pheochromocytoma – excessive catecholamines

- Portosystemic shunt – loss of medullary hypertonicity, increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

- Dwarfism – action unknown

- Acromegaly – osmotic diuresis due to diabetes mellitus

- Psychogenic polydipsia – loss of medullary hypertonicity

- Intestinal leiomyosarcoma – impaired tubular response to ADH

- Very low protein diet – loss of medullary hypertonicity

- Gastrointestinal disease (for example, ulcerative colitis)

- X-linked hereditary nephropathy – loss of medullary hypertonicity, increased GFR

- Renal dysplasia – loss of medullary hypertonicity, increased GFR

Latest news