30 Nov 2022

Diabetes mellitus in cats – a case-based approach

Kit Sturgess draws on examples of such cases to discuss management in feline patients.

In the UK, it is estimated that around 0.4% to 0.6% of cats have diabetes mellitus (DM; O’Neill et al, 2016; McCann et al, 2007).

The median survival time for diabetic cats is difficult to evaluate, as recent improvements in management have increased the numbers of cats that have transient diabetes. However, in cats that have long-standing diabetes, median survival times of 18 months are reported, but with a very wide range up to 10 years, with nearly half living longer than two years.

Restine et al (2019) reported on 185 cats receiving protamine zinc insulin with a loose control approach, with changes in insulin dose primarily adjusted in clinical response. The likelihood of remission in these cats was 56%, with an overall median survival time of 1,488 days (50 months).

This means the relationship between the owner and the practice is likely to be a long one – making trust, respect and clear communication a priority for successful management.

From the beginning of managing a case, it is important to discuss with the owner the criteria for success; for example, whether the aim is to control clinical signs or to try to achieve diabetic remission.

The appropriate approach will vary and is dependent on the owner-cat combination, with a number of factors needing to be taken into account to decide on the best approach and balance for a particular case.

Key factors that affect the management of diabetes in cats include:

- 80% to 90% of cats have type-two diabetes, meaning their hyperglycaemia is a mixture of both beta cell failure (rather than loss) and end organ (insulin) resistance. Hyperglycaemia results in glucose toxicity that impairs beta cell function; therefore, lowering blood glucose by exogenous insulin improves beta cell response to the point diabetes can be transient. Transient diabetes is reported in up to 85% of diabetic cats, although many clinicians feel that 40% to 60% is a more realistic figure. Transiently diabetic cats usually still have abnormalities of glucose metabolism, with 30% reported to relapse over a nine‑month period (Gottlieb et al, 2015).

- Hepatic gluconeogenesis plays a central role in glycaemic control in cats.

- In cats, amino acids are more potent secretagogues of insulin than glucose.

- Cats exhibit much lower postprandial increases in blood glucose than dogs, which means precise timing of feeding and insulin is less critical (including those fed ad lib) and the rationale for using a biphasic insulin is less clear.

- Cats tend to be less food driven than dogs and their physiology means they are less able to digest carbohydrate, and will use protein in hepatic gluconeogenesis regardless of dietary content. As such, current evidence indicates a high-protein/high-fat diet aids glycaemic control and increases the likelihood of cats going into remission.

- Cats tend to metabolise glucose quickly, so longer-acting insulins are usually required, even with twice-daily dosing.

- Cat insulin has a different amino acid sequence to pork, bovine and human insulins.

-

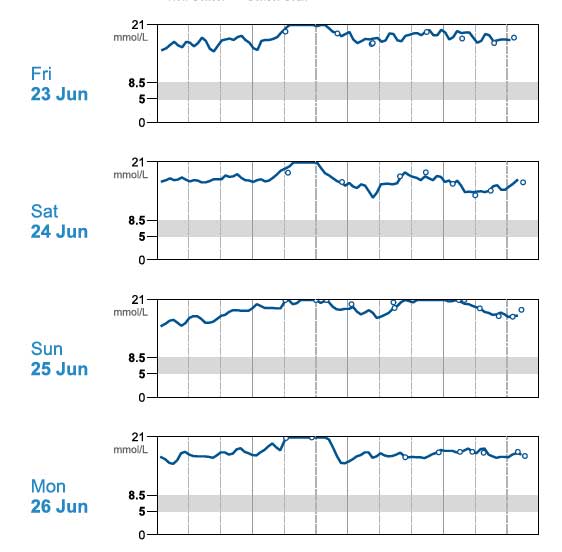

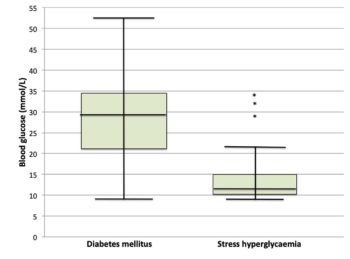

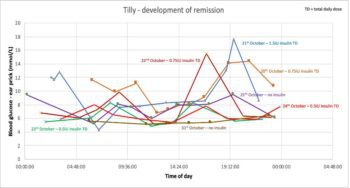

Figure 3. Tilly’s glucose curves on twice-daily biphasic insulin. Stress-associated hyperglycaemia is common in cats, meaning hyperglycaemia (even with glycosuria) is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of diabetes (Figure 1). The stress associated with hospitalisation can mean blood glucose curves performed in hospitalised cats may be poorly representative of blood glucose changes at home. However, blood glucose of more than 10.5mmol/L in an otherwise healthy cat should prompt further evaluation (Reeve-Johnson et al, 2017).

- Cataracts are a rare complication of DM in cats compared to dogs, but clinically apparent diabetic neuropathies appear more common.

- An estimated 10% of cats with DM are acromegalic.

- 90% of cats with diabetic ketoacidosis have concurrent disease.

Diabetic cat cases

Tilly

Tilly (Figure 2) – a 13.07-year-old, female, neutered, domestic medium hair cat – presented with a five-month history of unstable diabetes associated with polyuria and polydipsia (PU/PD), polyphagia and weight loss. Her day-to-day water consumption was variable and in-clinic glucose curves gave variable results (Figure 3). Tilly weighed 4.05kg and had received up to 5IU/kg of biphasic insulin twice‑daily.

Haematology

- Within reference intervals (WRI)

Biochemistry

- Blood glucose: 26.2mmol/L

- Alanine transaminase: 55IU/L (reference <40IU/L)

- Remaining parameters WRI including alkaline phosphatase 26IU/L (reference <50IU/L)

- Urea 9.3mmol/L (reference 4mmol/L to 12mmol/L)

- Creatinine 123µmol/L (reference <140µmol/L)

Blood pressure

- Doppler: 145mmHg mean systolic

Urinalysis

- +++ glucose, equivocal proteinuria (UPC 0.22), USG 1.025 and pH 5.5, sediment inactive and culture negative

Feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity

- 1.4µg/L (reference 0.1µg/L to 3.5µg/L)

Thyroxine

- 12.9nmol/L (reference 15nmol/L to 40nmol/L) – assumed euthyroid sick

Abdominal ultrasound

- Liver: mildly enlarged and coarsely granular, with increased general echogenicity and slightly patchy texture

- Kidneys: mild-moderate reduction in corticomedullary definition, pelvis normal, even rounded outline, normal size

- Left adrenal: plump and rounded with diameter >4mm, relatively hypoechoic

- Pancreas: view obstructed by faecal material and small intestinal gas

Physical examination was unremarkable apart from a grade III/VI left parasternal pansystolic murmur that was not investigated further. Investigations are outlined in Panel 1; no clear other disease was identified.

Based on the glucose curves performed, it was felt duration of action of the insulin was too short and the dose rate may be resulting in over-swing at home. Tilly was started on 1IU of protamine zinc insulin twice‑daily and her diet changed to a high-protein/high-fat wet food.

After two weeks, the glucose curve showed significant improvement and the owner elected to monitor at home. Tilly’s glycaemic control continued to improve and she went into sustained diabetic remission (Figures 4 and 5).

Learning points

Biphasic insulin may be too short‑acting in some cats and the short-acting component can lead to rapid blood glucose changes worsening over-swing, as postprandial hyperglycaemia in cats can be small.

Time to diabetic remission in cats is very variable, from a few weeks to several months. As glucose toxicity reduces and insulin efficacy increases, cats can appear to become less stable. At this point, over-swing can develop that can appear as apparent resistance – particularly on short-term, in-clinic glucose curves, leading to insulin dose increase worsening the over-swing (as in this case).

Reducing insulin dose rates along with considering the use of a longer-acting insulin dose with a less pronounced peak effect in unstable diabetic cats may result in improved control.

Mimi

Mimi (Figure 6) – an 11.02-year-old female, neutered Siamese cat – was referred with a history of gradual weight loss over six to eight weeks, lethargy and inappetence; the owner estimated Mimi was consuming around two-thirds of her usual amount of food.

Mimi had vomited once and she was urinating in the house. Haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis already performed showed:

- bilirubin – 19µmol/L (reference is less than 10µmol/L)

- haematocrit – 19.5% with a poorly regenerative phenotype

- blood glucose – 18.9mmol/L with fructosamine 430µmol/L (reference is less than 350µmol/L)

- urinalysis – +++ glycosuria

- total thyroxine – 26nmol/L (reference is 15nmol/L to 40nmol/L)

A presumptive diagnosis of DM had been made.

On physical examination, Mimi was quiet, but responsive. She has lost considerable weight (42% of bodyweight), 3.48kg with a body condition score of 2 out of 9. Heart rate was 204bpm; pulse quality was poor.

Mimi purred continually, making thoracic auscultation difficult. Mucous membranes were pale. Mimi has third eyelid prominence associated with enophthalmos and a bilateral purulent ocular discharge. No goitre was palpable. Superficial lymph nodes were within normal limits. Abdominal palpation seemed uncomfortable; one of the loops of small intestine felt thickened.

Causes of weight loss can be broadly categorised into:

- lack of calorie intake

- malabsorption/maldigestion

- hypermetabolic states

- excessive calorie loss

Although inappetent, the weight loss was felt to be too great for pure protein calorie malnutrition. DM would potentially account for weight loss associated with excessive calorie loss in the urine and relative insulin deficiency, causing protein and lipid catabolism.

Rapid weight loss, along with the changes in lipid metabolism, could also be causing hepatic lipidosis, accounting for the inappetence rather than polyphagia. The periuria could be an expression of PU/PD. However, the thickened loop of small intestine was of unknown significance, making imaging appropriate, even though no significant gastrointestinal signs had been reported.

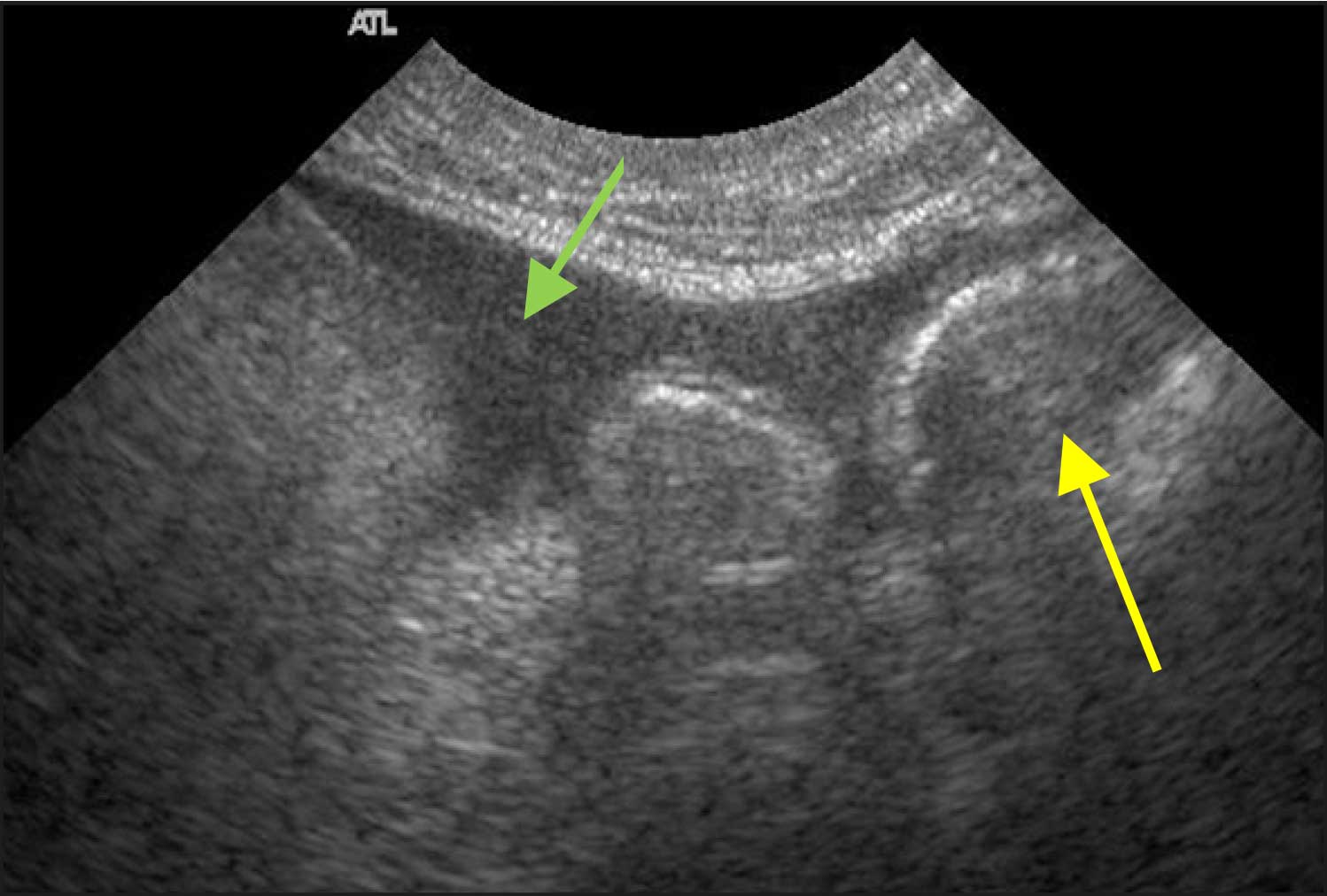

Radiography and ultrasound (Figures 7 and 8) showed a linear soft tissue density consistent with an obstruction of the terminal ileum. Ultrasound confirmed a mass lesion distal to dilated bowel in the ileum. The mass lesion had poor wall structure that was primarily hypoechoic.

Mesenteric lymph nodes were enlarged. A small volume, non-septic, peritoneal effusion was present. Mimi’s spleen was prominent and her liver enlarged.

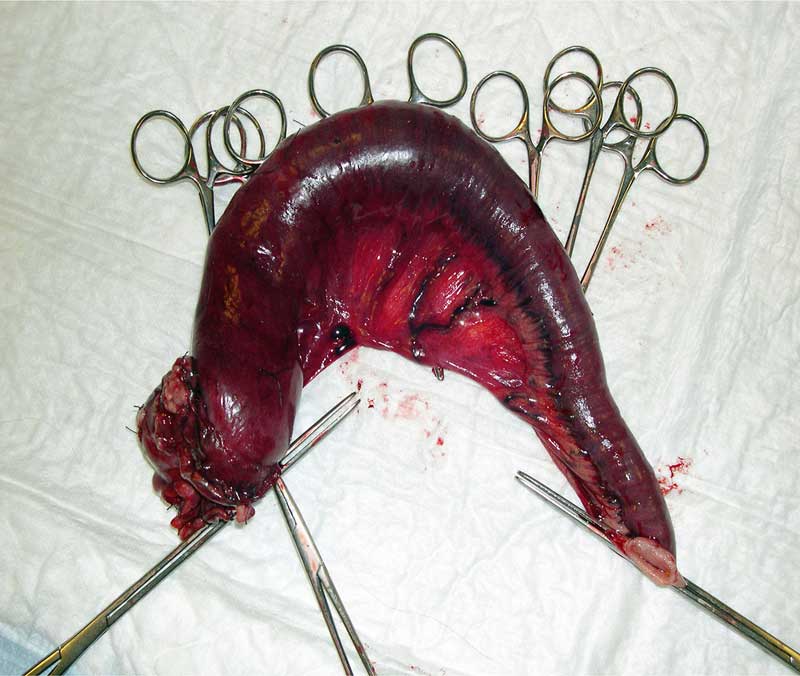

Exploratory laparotomy was performed and the thickened loop of intestine resected (Figure 9) along with an enlarged lymph node; biopsy of the liver was performed.

Histology revealed low-grade hepatic lipidosis and a metastatic mucus-producing adenocarcinoma.

Learning points

Severe metabolic stress can cause hyperglycaemia that can be of sufficient duration to lead to elevated fructosamine, complicating the diagnosis of DM in cats.

Common

- Polyuria

- Polydipsia

- Weight loss

- Polyphagia (more variable)

- Lethargy and depression

- Owners may be unaware of some signs due to the lifestyle of cats; for example, polyuria and polydipsia

Less common

- Vomiting

- Plantigrade stance

- Muscle weakness and wasting

- Poor hair coat

- Dehydration

Where clinical signs (Panel 2) and physical findings are not typical for DM, further investigation is warranted.

Henry

Henry (Figure 10a) – a 13-year-old, male, neutered Siamese cat – presented as an emergency with a five-month history of DM. He was receiving 2IU of biphasic insulin every 12 hours.

The owner reported that he was usually moderately PU/PD, but over the past 24 hours, he had stopped eating and drinking, and started vomiting.

On physical examination, Henry was collapsed and poorly responsive. Skin tenting suggested significant dehydration, estimated at 8% to 10%. Temperature was subnormal at 36.5°C with a low heart and pulse rate of 115bpm. Respiratory rate was mildly elevated at 32 breaths per minute, with unremarkable thoracic auscultation. The abdomen was relaxed, non-painful and unremarkable; the bladder was moderately full, kidneys smooth and mobile, and intestines of expected compliance. Henry had not lost appreciable weight over the past six weeks and weighed 4.75kg. Blood pressure was low at 75mmHg mean systolic.

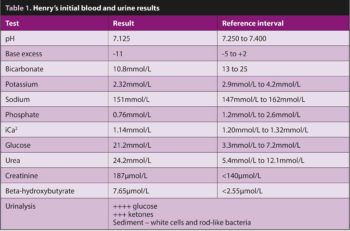

Although a significant number of differential diagnoses was possible, given his known history and evidence that Henry’s circulation was collapsing, a rapid blood screen and urinalysis were conducted to assess his diabetic status and direct initial treatment; results are in Table 1.

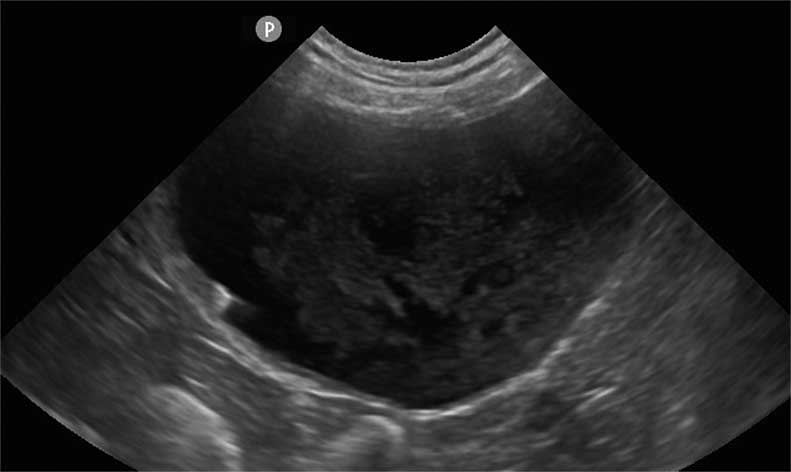

Brief abdominal ultrasound to collect a urine sample – and exclude other major pathology – showed a large amount of debris in the bladder lumen (Figure 10b). The initial screen was consistent with diabetic ketoacidosis, potentially secondary to a urinary tract infection with the possibility of pyelonephritis.

Initial therapeutic decisions

Initial therapeutic decisions were:

- IV fluid therapy – Hartmann’s solution initially at 10ml/kg/hour.

- Correct hypovolaemia and support blood pressure.

- Support kidneys to resolve acid-base disturbance.

- Potassium supplementation – 40mmol/L of fluid.

- IM neutral insulin 2IU every one to two hours.

- IV marbofloxacin – assumption that bacteria seen were likely to be coliforms.

Monitoring

Rapidly changing acid-base status and blood glucose can have a number of consequences. Key concerns in Henry’s case were:

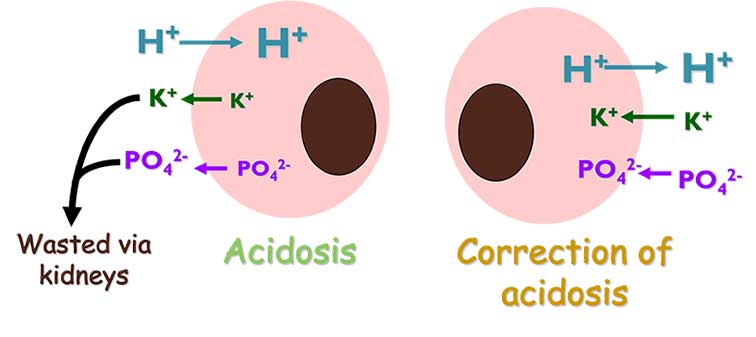

- Development of severe hypokalaemia – in acidotic patients (Figure 11), potassium moves from the intracellular to extracellular space to mediate the acidosis. On correction of the acidosis, the potassium moves back, potentially leading to life-threatening hypokalaemia.

- Development of severe hypophosphataemia – in acidotic patients (Figure 11), phosphate moves from the intracellular to extracellular space to mediate the acidosis; on correction of the acidosis the phosphate moves back, potentially leading to severe hypophosphataemia than can result in intravascular haemolysis.

- Development of hypoglycaemia – as blood glucose falls in response to the IM insulin, cellular metabolism may need to be supported by additional glucose in the IV fluids – supplementation (2.5% solution) is usually started if blood glucose drops below 15mmol/L.

- Development of paradoxical cerebral acidosis:

- Correction of acidosis generates CO2.

- Most of CO2 removed by lungs.

- Some diffuses across the blood brain barrier and recombines with water to produce H+ ions (H20 + CO2 – H2CO3 – H+ + HCO3).

- Progressive worsening of neurological signs despite therapy is a key warning sign.

Blood pressure was continually monitored, along with pulse, respiration and mental status.

Blood glucose, pH, electrolytes, and phosphate levels were initially measured 30, 60, 120 and 240 minutes after the initial triage.

Outcome

Henry showed a gradual improvement in mentation and demeanour, phosphate supplementation was not required, and urine culture revealed a moderately resistant Escherichia coli.

Henry was discharged after three days of hospitalisation.

Bonnie

Bonnie (Figure 12) initially presented with acute onset lethargy and inappetence. She was jaundiced with significantly raised liver enzymes. A diagnosis of obstructed jaundice secondary to pancreatitis was made.

A year later, Bonnie re-presented with weight loss, PU/PD and polyphagia associated with the development of DM. It was assumed, in Bonnie’s case, that this was most likely due to an absolute lack of insulin (type‑one phenotype), associated with a loss of pancreatic beta cells due to chronic pancreatic fibrosis.

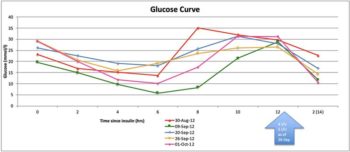

Despite insulin therapy with 5IU of glargine insulin, glycaemic response appeared poor; although, it was unclear whether this was due to over-swing or insulin resistance. Bonnie would not tolerate repeated in-hospital glucose measurements and the owners were unable to perform home monitoring, so a flash glucose monitor was placed. Results from the monitor are shown in Figure 13, indicating insulin resistance.

Although insulin resistance can develop secondary to over-swing and can last for several days, the duration of hyperglycaemia in Bonnie’s case was too long. Further investigation was conducted, including measurement of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) to look at the possibility of acromegaly. IGF-1 was more than 2,000ng/ml, consistent with acromegaly, and CT confirmed the presence of a pituitary mass (Figure 14).

Learning points

Where hyperglycaemia is persistent, differentiating over-swing and secondary insulin resistance can be challenging – continuous glucose monitors are hugely valuable and cost‑effective, allowing blood glucose to be monitored for up to 14 days.

Bonnie had no external features consistent with acromegaly, but physical characteristics are an insensitive rule-out and measurement of IGF-1 is required.

Note in untreated diabetic patients, IGF-1 levels can be suppressed, so measurement should be delayed until insulin therapy has been initiated.

Conclusions

DM is a fascinating, if challenging and sometimes frustrating disease in cats.

Cats with DM are more like people than dogs, and ideally, the aim with all new diabetics is to try to achieve remission, but this requires the ability to establish a good long-term relationship with the owner, and a clear understanding of their priorities and criteria for success.

Recent developments in technology – in the form of easily useable and relatively inexpensive continuous glucose monitoring systems – have provided a valuable additional tool to help us understand our feline DM patients.

All patients teach us something – capturing these learnings is a vital part of developing our clinical practice.