16 Jul 2018

Dietary therapy for dermatological disorders in companion animals

Marge Chandler considers skin conditions as a result of nutrient-deficient diets and looks at treatments, such as elimination trials.

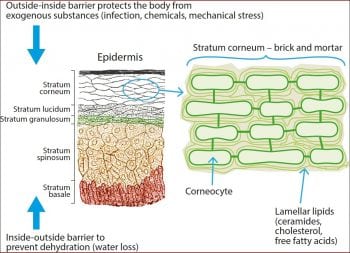

One of the most important functions of skin is as a barrier – preventing water loss (inside to outside) and protecting the body from the environment (outside to inside; Figure 1).

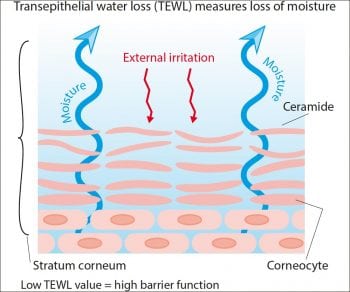

The barrier function is dependent on the stratum corneum (SC). It has been suggested atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a defective barrier function. One study that assessed barrier function with transepidermal water loss (TEWL) – the volume of water passing from inside to outside the body through the upper epidermal layers – found a higher TEWL in dogs with AD versus controls (Cornegliani et al, 2011; Figure 2). Additionally, treated AD dogs had lower TEWL compared to non-treated – suggesting skin barrier function can be improved by treatment.

Nutrition is important to ensure a healthy skin barrier (Hensel, 2010). Nutritional modification can likely improve skin barrier function in dogs and cats with disease, and promising research exists in this area. Several nutrient deficiencies can affect the skin and incorrect dietary supplementation, such as excess calcium and phosphorus, may unbalance a diet. In puppies, for example, excess supplementation with calcium and/or phytates is a major cause of zinc-responsive dermatosis.

Nutrient deficiency and skin disease

The skin is the largest organ in the body and has a high turnover rate, so nutrient deficiencies can result in dermatopathies (National Research Council, 2006; Outerbridge, 2012; Popa et al, 2011; Reiter et al, 2009; Watson et al, 2006). Nutrient deficiencies that can cause skin signs (Figures 3 and 4) include protein and some amino acids, omega-6 essential fatty acids (EFAs), fat-soluble vitamins, B vitamins and trace elements including zinc. These deficiencies are unlikely in healthy pets fed complete and balanced diets. Unbalanced diets, including home-made ones, can result in any or all of these deficiencies.

Protein and amino acids

Hair is 95% protein and certain amino acids are especially important for healthy hair – for example, methionine, cysteine and tyrosine. Protein and amino acids provide substrates for keratinisation, pigmentation and hair growth.

A substantial portion of daily protein requirements is used for skin and hair production, and protein deficiency can cause thin, dull, brittle hair. Tyrosine is a precursor for melanin and a deficiency can cause a reddening of black hair.

Trace minerals

Copper

Copper serves as a cofactor in enzymatic conversion of tyrosine to melanin and a deficiency can cause changes in pigmentation.

Zinc

Zinc-dependent metalloproteinases are involved in keratinocyte migration and wound healing. Syndromes are associated with zinc deficiency and include lethal acrodermatitis of bull terriers, zinc-responsive dermatosis (ZRD)syndrome one in huskies and malamutes, ZRD syndrome two in puppies fed a zinc-deficient diet, and “generic” dog food dermatosis.

- Lethal acrodermatitis of bull terriers is a complete dysfunction of zinc metabolism. Signs include impaired growth, eating difficulty, crusting and scaling of the feet and pads, and splayed digits. It does not respond to zinc supplementation and has a high mortality rate.

- ZRD syndrome one results from a genetic defect that reduces zinc absorption and is more prevalent in northern breed dogs (for example, huskies and malamutes). It requires lifelong oral zinc supplementation (2mg to 10mg elemental zinc/kg empirically recommended).

- ZRD syndrome two is seen in rapidly growing large breed dogs or dogs on diets high in phytates and other zinc-binding compounds (for example, calcium). It resolves after a change to a diet with greater zinc concentrations and/or with reduced zinc-binding compounds.

- Dermatosis associated with “generic” (some cheap) dog foods may be due to a relative inadequacy of zinc. Therapeutic levels (approximately 1.1mg/kg/day to 2.2mg/kg/day of elemental zinc) have been used to treat a dry, crusting dermatosis characterised on histopathology by a diffuse parakeratotic hyperkeratosis.

Zinc methionine supplementation to dogs with mild to moderate, chronic AD had reduced canine AD lesion index, and in some dogs the dose of other medications (for example, corticosteroids or ciclosporin) could be reduced (McFadden et al, 2017).

Not all zinc supplements are the same; zinc sulfate, zinc gluconate and zinc methionine are all acceptable, but must be prescribed according to their individual concentrations of elemental zinc. Over-supplementation of zinc may result in gastrointestinal (GIT) upset and haemolysis – especially in cats.

Fat-soluble vitamins

Vitamin A is a group of fat-soluble retinoids critical for epidermal differentiation and normal sebum production. Deficiency is uncommon, but can cause skin scaling, poor hair coat and alopecia. While vitamin A is very important for all epithelia, and its deficiency results in altered skin barrier function, no data exists to support extra supplementation to help skin barrier function.

Vitamin A-responsive dermatosis

Cocker spaniels are the breed most commonly affected by vitamin A-responsive dermatosis, though other breeds can be rarely affected. Lesions are characterised by abnormal cornification, hyperkeratotic plaques, abnormal sebum, epidermal scaling, alopecia and secondary pyoderma. Biopsy specimens show orthokeratotic and follicular hyperkeratosis. Oral retinol (vitamin A) reportedly ameliorates clinical signs; however, the optimal dose is unknown (empiric dose is 10,000IU/dog q24h or 1,000IU/kg q24h).

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is the primary antioxidant in the cell membrane and includes any of four tocopherols and four tocotrienols. α-tocopherol is the form with greatest activity in cells, although others may be added to commercial diets as natural preservatives. Vitamin E protects fatty acids (including those in the SC) from oxidative damage.

Experimental deficiency causes alopecia, seborrhoea and increased cutaneous infections. In cats, a deficiency can result in pansteatitis (for example, cats fed a diet high in polyunsaturated fats as in some seafoods) resulting in firm, painful swellings due to inflammation from adipose tissue perioxidation. Affected cats display a reluctance to move, signs of pain and are often febrile.

A study found dogs with atopy had lower plasma vitamin E, and supplementation (8.1IU/kg q24h for 8 weeks) improved the subjective pruritus score; however, it is unknown whether this relates to improvement of skin barrier function (Plevnik et al, 2014).

B vitamin deficiencies

Deficiencies of biotin, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid and pyridoxine may be associated with skin disorders. A positive effect has been seen on TEWL of healthy dogs with a diet supplemented with pantothenic acid, niacin, choline, inositol and histidine. These nutrients showed in vitro stimulation of ceramide synthesis in canine keratinocytes (Watson et al, 2006), while a small study in Labrador retriever puppies fed this combination of nutrients suggested it could help reduce itching when fed for one year (van Beeck et al, 2015). However, very little data exists on the effects of supplementing these nutrients separately and no information exists on how this combination improves skin barrier function.

EFAs

EFAs include those from the omega-6 and omega-3 families. Omega-6 EFAs are more potent than omega-3s for skin barrier function. Linoleic acid is an omega-6 EFA incorporated in the ceramides of the SC and deficiency results in dry, coarse skin (Reiter et al, 2009). Some high-fat diets or vegetable oil supplements can improve hair coat quality in dogs. EFAs may improve zinc absorption. Zinc and linoleic acid supplementation together reduces TEWL. Safflower and corn oil contain the most linoleic acid; palm, olive and coconut oils are all low in it.

Oral supplementation with EFAs (especially linoleic acid) may improve ceramide synthesis in dogs, although studies are still scarce and more data are needed to confirm their effect and the appropriate route, dose and composition of the treatment (Popa et al, 2011). For maintenance, 2% of the total caloric intake should be linoleic acid.

Excessively high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids can interfere with the use of vitamin E. Even with antioxidants and good levels of EFAs, fatty acids in nearly all dry foods will become oxidised when stored for more than six months.

Omega-3 fatty acids

Omega-3 fatty acids – for example, eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, result in the production of cytokines with less inflammatory characteristics than those derived from omega-6 EFAs. They may decrease pruritus in dogs and skin inflammatory responses in cats (Logas and Kunkle, 1994; Park et al, 2011). Omega-3 fatty acids originate in phytoplankton and algae, which are consumed by fish. Some fish (for example, herring, mackerel and salmon) store these fatty acids in their muscles, while others (such as cod) store them in their livers. Excessive supplementation of the diet with cod liver oil may result in vitamin D toxicity.

Microbiome and probiotics

The sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA genes shows the human skin surface inhabited by a highly diverse and variable microbiota; similarly, a dog’s skin is also inhabited by rich and diverse microbial communities (Hoffman et al, 2014). Sequence data shows high individual variability between samples. Differences in species richness were also seen between healthy and allergic dogs, with allergic dogs having lower species richness compared to healthy dogs.

Probiotic products differ widely in composition and number of microbes; however, evidence has shown some products have an immunomodulatory effect. Their use has been suggested as an adjunct treatment for canine AD. Administration of the probiotic strain Lactobacillus sakei probio-65 for two months significantly reduced the disease severity index in experimental dogs’ AD (Kim et al, 2015). Another study showed probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei K71, used as a complementary therapy, provided a corticosteroid and ciclosporin sparing effect (Ohshima-Terada et al, 2015).

Cutaneous adverse reaction to food and food-induced atopic dermatitis

A complete response exists to diet restriction-provocation in cutaneous adverse food reactions (CAFR). In food-induced AD (FIAD) a partial response to diet restriction-provocation exists. Foods can be a trigger for FIAD, but sensitisation to environmental allergens, a poor skin barrier and altered skin inflammation also contribute. In many pets, signs start at a fairly young age – between one and four years. Between 30% and 50% show signs younger than one year.

As owners will note no change in diet has occurred, it is important to note the foods may have been fed for two years or more in some cases. Clinical signs are non-seasonal, with seasonal flares associated with environmental allergies. Skin and GIT signs are seen in 30% to 60% of dogs and 10% to 30% of cats. Head and neck dermatitis is particularly associated with feline adverse food reactions (AFRs).

Any protein can be an allergen. Most dogs react to more than one ingredient. Most allergens are 10 kilodaltons (kD) to 70kD glycoproteins. Food allergens include beef, dairy, chicken, lamb, wheat, soy, egg, pork, fish and rice (Outerbridge, 2012).

Choosing a diet for an elimination trial

Diets for an elimination dietary trial can be home-cooked or commercial (see later). Choosing novel ingredients can be difficult as owners may not remember or know what has been fed, or may not know all the ingredients in foods, treats and supplements. Recipes vary and some specific ingredients may not be listed. In two studies, DNA from undeclared proteins were found in 10 of 12 and in 9 of 10 tested foods (Ricci et al, 2013; Horvath-Ungerboeck et al, 2017).

Cross-reaction among food allergens

Potential cross-reactions among food allergens exist that are more frequent and stronger among related allergens, including some considered “exotic”. For dogs, cross-reacting ingredients include beef and lamb, and in poultry, include chicken, duck and turkey. Mammalian and avian ingredients do not cross-react (Nuttall and Chandler, 2017).

Effect of food processing on allergenicity

Food processing, including heating, can decrease or increase the allergenicity – generally decreasing it by destroying conformational epitopes, although the Maillard reaction (glycation when heating amino acids and reducing sugars – for example, browning of foods) may increase it.

An abstract from a small study in dogs showed raw horse meat and canned products had fewer proteins reacting with IgE, compared to dry foods and cooked horse/potato; however, cooked fish proteins were less reactive with IgE compared to raw fish (Favrot et al, 2016).

Food allergen serology

Only two serology tests are validated. The Sensitest IgE ELISA (Avacta Animal Health) has an approximate positive predictive value of 30% and negative predictive value of 80%. This means for every three dogs with a positive IgE titre, only one is allergic to that food; and for every five negative dogs, four are not allergic to that food.

The Cyno-Dial (Galileo Diagnostics) test uses western blots of whole diets, rather than individual proteins. Approximately, the positive predictive value is 79% and the negative predictive value is 78%. These tests should not be used to diagnose a food allergy, but may identify suitable ingredients for diet trials (Nuttall and Chandler, 2017; Hagen-Plantinga et al, 2017).

Home-cooked diet trials

Home-cooked diets can be difficult and time-consuming to prepare, although many owners like to cook for their pet. More importantly, most home-made diets are not balanced for long-term feeding. If a diet is to be fed long term it should be formulated by a veterinary nutritionist. Zinc and EFAs – nutrients especially important for skin health – are often deficient in diets made by owners.

Novel protein diets

Novel protein diets are meant to contain a single protein source, and one not previously fed to that pet should be chosen. While some of these are marketed as “hypoallergenic”, this is only true if that pet does not react to any of the ingredients. These are complete and balanced, although if the owner has fed a variety of diets it may be possible to find a diet that contains novel ingredients. Veterinary novel protein diets are a better choice than some over-the-counter diets, as these may contain other proteins (Raditic et al, 2011).

Hydrolysed diets

Hydrolysis reduces the proteins to less than 5kD to 10kD, theoretically making them non-immunogenic, although partial hydrolysation leaves larger (potentially allergenic) fragments. The degree of hydrolysis is important. Up to 50% of dogs with CAFR, enrolled in three controlled studies, exhibited increases in clinical signs after ingesting partial hydrolysates derived from foods to hydrolysed diets (Olivry and Bizikova, 2010). When possible, avoid source proteins the pet has eaten. Different pets like different hydrolysed diets, so it is worthwhile to try different foods if the first one is not accepted.

Grain and gluten

Owners are often concerned about grain and gluten. Maize, rice and wheat proteins are highly digestible. Coeliac disease has not been described in dogs and cats, and allergies to gluten are uncommon in pets. In some border terriers, a neurological condition named Spike’s disease (canine epileptoid cramping syndrome) responds to a gluten-free diet. Some Irish setters had an intestinal disorder due to gluten, although this is rarely, if ever, seen.

Dietary elimination trials

For a successful diet trial, it is necessary to explain to the owner the reason for it and discuss problems he or she may have with exclusive feeding (for example, other pets, a family member who may not comply, scavenging or hunting).

In the diet history, consider flavoured medications, toothpaste, treats and scraps, hidden ingredients, eating faeces, discarded and dropped food, and food given for medication. As owners will continue to give treats, discuss treat options, such as baked kibble or canned food or vegetables.

Compliance can be helped by allowing short courses of glucocorticoids or oclacitinib for three to five days for pruritus (Nuttall and Chandler, 2017). Infections and ectoparasites should be treated prior to, or during, the trials. The optimum length for a food trial for dermatological signs is eight weeks.

GIT signs usually respond in one to two weeks, followed by acute then chronic skin lesions. If the GIT signs haven’t resolved in two to three weeks, consider compliance problems or change the food. A food challenge will confirm the cause. Animals with AFRs should relapse within 14 days. Owners may be understandably reluctant to challenge due to fear of relapse; many owners just wish to test a few foods and treats or stay with the trial diet. If the diet is complete and balanced, that may be a reasonable approach.

Food trials in cats

Some cats prefer variety and a risk of hepatic lipidosis exists if they don’t eat – even for a few days. Many cats will eat food from other pets in the home or hunt outdoors, and it can be difficult to keep an outdoor cat indoors. Commercial veterinary novel protein, hydrolysed protein diets, or complete and balanced home-made diets can be good choices (Figures 5 and 6).

Latest news