27 Mar 2018

Equine colic: diagnosis, treatment and determining need for surgery

Figure 1. Safety should always be the first priority when dealing with a horse with severe colic. It may be necessary to try to administer sedatives to the horse prior to examination.

Managing the horse with colic remains one of the biggest challenges facing the equine clinician. Colic signs can vary in severity, and great pressure can often exist to make a working diagnosis and a rapid decision about whether referral level care or surgery is necessary.

These decisions are often not easy when you are faced with a horse showing non-specific signs of abdominal pain. This article runs through the approach to examining and managing a horse with colic.

Signalment

Some conditions are much more commonly recognised in certain ages and breeds of horses. For example, a strangulating lipoma should always be considered in an older (more than 15 years) horse or pony, a large colon volvulus in a post-foaling broodmare and a small colon faecolith in a miniature pony.

History

History is an essential first step, as many important clues can be identified. The level of detail required from the history becomes increasingly important with milder or more chronic colic signs. In a horse showing acute, severe colic, a brief history may be all that is required.

Examples of subjects to consider include:

- duration and severity of colic signs

- previous colic or weight loss

- diet and any recent change

- recent medication

- management regime and any recent change

- exercise regime and any recent change

- worming history

- soil type if at pasture, and any change in turnout duration or location

- any stereotypical behaviours, for example, windsucking or crib biting

Changes in management are especially important. For example, a pelvic flexure impaction is a common diagnosis in a horse moved from full turnout or exercise to box rest because of an injury. Sand colic is common in horses at sandy pasture in the winter, while horses that windsuck are more prone to tympany and colon displacements.

Other factors should also be considered, especially if colic signs are mild or unusual, such as weight loss, unusual behaviour or other symptoms.

Administered medication can also be relevant – for example, right dorsal colitis or equine gastric glandular disease can occur after NSAIDs are given. Other scenarios that might be relevant include access to toxins, such as sycamore seeds, or lameness, if there is any concern the clinical signs may be related to non-abdominal pain such as atypical myopathy or laminitis.

Clinical examination

A careful clinical examination will always remain the most important part of examining any horse with colic. While this will not always allow you to make a primary diagnosis, it should enable you to make a decision about possible underlying causes, the severity of the situation and the requirement for urgent treatment.

The importance of repeated clinical examinations should also not be underestimated. Even when the primary assessment is unrewarding, a great deal of information can be gained when evaluating changes in clinical parameters and pain level over time.

The first consideration when examining a horse with severe colic should be safety (Figure 1). In some instances, it is very difficult, or impossible, to examine the horse without any chemical restraint or analgesia.

Top priority should be given to maintaining your own safety and the safety of owners/handlers. The most useful medications to use in the emergency situation, to provide both sedation and analgesia, include a combination of the alpha-2 agonists and an opioid.

A number of different options exist, but the combination of detomidine (10µg/kg to 20µg/kg) plus butorphanol (25µg/kg) IV is a reliable choice. If IV access is not possible, then double the above doses can be given IM and the horse should be left undisturbed for 20 to 30 minutes or until visible signs of sedation appear.

Higher doses of both medications can be used and may be necessary to provide longer-term analgesia.

When safe, a full clinical examination should be carried out. If possible, it is useful to carry out a brief assessment of clinical parameters prior to administration of any medication.

Evaluation of the cardiovascular system should focus on hydration status, signs of hypovolaemia or evidence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Tachycardia can be caused by pain and stress, but the presence of tachycardia (especially a heart rate above 60 beats per minute), in conjunction with other signs of cardiovascular dysfunction – such as tacky or dry mucous membranes or delayed jugular refill – suggests the possibility of a more serious underlying problem.

Fluid sequestration into the intestinal tract, secondary to a strangulating lesion or complete obstruction, can rapidly lead to marked hypovolaemia. The presence of dark discolouration or congestion of the mucous membranes suggests the presence of SIRS, which may be associated with the presence of a strangulating lesion or intestinal ischaemia.

The abdomen should be evaluated for signs of distension (Figure 2), which is often a sign of large intestinal tympany, and the presence and quality of borborygmi should be assessed. Borborygmi should be assessed over four quadrants (paralumbar fossa and ventral flank on both sides). Auscultation of the ventral abdomen can also be useful to aid evaluation for the presence of sand.

Assessment of the level of pain is a critical part of the colic examination. Persistent, severe pain remains one of the most reliable indicators of a surgical problem and should never be dismissed.

The clinical examination should also include the assessment of other body systems and presence of unusual clinical signs. This is especially important in identifying horses whose clinical signs are being caused by non-abdominal pain, for example myopathy, laminitis or neurologic disease, or for horses where the colic signs are more likely to represent a symptom of a more complicated underlying intestinal problem. Examples of unusual findings are shown in Figure 3.

Rectal examination should be considered as part of the clinical examination when it is safe to do so. Personal safety considerations include the environment, the horse’s age and temperament, and degree of pain.

If you are confident the horse can be adequately restrained, rectal examination should be carried out after use of sedation, and possibly IV hyoscine butylbromide to provide rectal relaxation (0.3mg/kg).

Performing the examination with the horse backed up to a door frame can offer a small degree of protection. The horse’s safety should also be considered and rectal examination should generally be avoided in young, small or very fractious animals.

When performing an examination, a careful, systematic examination of the abdominal cavity should be carried out. The examination should evaluate for the presence of large or small intestinal distension, abnormal positioning of the intestinal tract – either due to its location or the presence of tight taenial bands – abnormal contents of the intestinal tract (impacted material or fluid contents) and presence of abnormal masses.

Evaluation of findings

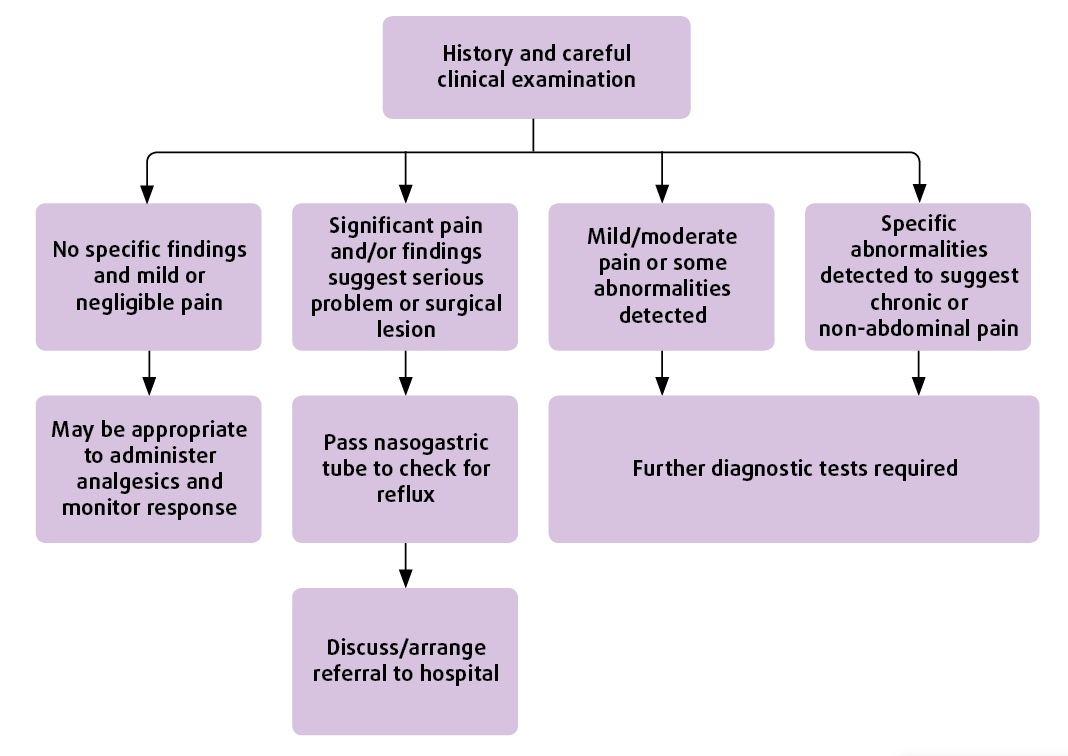

At this stage in the examination, it is usually possible to make a preliminary decision on how to proceed, as shown in Figure 4. Mild, non-specific colic is very common, and for the vast majority of horses examined in a first opinion setting the only treatment necessary may be to provide mild analgesia.

If the horse is showing minimal signs of pain, it has no significant history of prior colic, and clinical examination has failed to reveal any significant abnormalities, then administering a single dose of an NSAID may be appropriate. It is generally considered best to avoid flunixin, due to the concern this medication may mask signs of ongoing pain – although this is debatable. Other choices include phenylbutazone (4.4mg/kg IV) or meloxicam (0.6mg/kg IV).

In a second subset of horses your examination will have raised significant concerns about the possibility of a surgical problem. For example, if your clinical findings have included evidence of significant pain, signs of SIRS and hypovolaemia, and rectal examination has revealed distended loops of small intestine, there is little point in carrying out any further investigation – and immediate referral to a surgical facility should be organised, if possible.

In these instances, it is essential to pass a nasogastric tube, prior to referral, to allow gastric decompression. It may also be necessary to provide further analgesia to travel, with further sedation and/or an NSAID. In these cases, providing a higher dose of butorphanol (up to 0.1mg/kg IV) can be useful.

It can be tempting to try to provide fluid resuscitation prior to referral, but in reality it is usually better to try to expedite the horse’s arrival at a hospital facility.

If referral is not an option, it may be appropriate to provide further treatment or recommend immediate euthanasia.

The most challenging cases are the ones that do not fit into either of the first two categories. These are horses that continue to show recurrent signs of colic or fail to respond well to analgesia. In these cases, further investigation (or again immediate referral) is usually necessary.

Blood work

Being able to carry out some point-of-care bloods can be very helpful in identifying the severity of underlying disease and to help guide therapy. The use of portable lactate machines can enable a rapid assessment of the adequacy of tissue perfusion.

As a general rule, the higher the lactate concentration, the more serious the underlying disease. Identifying a high lactate concentration (greater than 3mmol/L) in a horse with equivocal clinical signs should prompt consideration of the need for more aggressive treatment.

If the horse is located close to your practice, carrying out further blood work, including measurement of packed cell volume (PCV) and total solids (TS) – plus possibly basic haematology and biochemistry – can be useful. Increased concentrations of PCV and TS suggests hypovolaemia, and, again, should prompt consideration of more aggressive treatment.

A relatively low TS concentration can be seen in horses suffering from chronic protein losing enteropathy or acute problems, such as colitis. In horses with recurrent colic, evaluating a full haematology and biochemistry profile can help you look for possible underlying causes.

Abdominal ultrasound

This is one of the most useful techniques in evaluating any horse with colic (Figure 5). To gain the most useful information, a low frequency transducer (2MHz to 4MHz) should be used to allow a depth of penetration of 25cm to 30cm.

The most time-efficient way to carry this out in the emergency situation is to use surgical spirit over a horse’s coat to provide contact. This can be challenging in fat, hairy, muddy or sweaty horses, and in these instances it may be necessary to clip some of the haircoat.

Different techniques allowing rapid assessment of the abdomen with ultrasound have been described, such as the fast localised abdominal sonography of horses (FLASH) protocol. The author’s preferred approach is to start scanning in the left paralumbar fossa and then scan down towards the ventral abdomen. The probe should then be advanced cranially, scanning through every rib space right up the cranial abdomen near the point of the elbow.

The main structures that should be identified include the left kidney, spleen, colon, stomach and ventral lung margin. Small intestine is variably seen on this side.

The ventral abdomen should then be scanned from the inguinal area cranially in three or four planes. Small intestine should be reliably identified in the inguinal region, with ventral colon visible more cranially. The presence and echogenicity of free abdominal fluid should be assessed ventrally.

The right hand side of the abdomen should then be scanned in a similar way to the left. Structures that should be identified include caecum, colon, kidney, duodenum, liver and ventral lung margin. The right cranial flank is a good location to look for the presence of distended taenial vessels, which can be identified with certain types of colon displacement. Examples of ultrasound findings are shown in Figure 6.

Abdominocentesis

This procedure can provide very useful additional information. However, it is not without risks, including intestinal laceration and subsequent peritonitis, so it should be used when there is a clinical indication.

A variety of techniques exist to collect a sample of abdominal fluid, but the quickest way is the use of a 2in, 19-gauge needle in the cranioventral abdomen after sterile preparation of the skin (Figure 7).

Normal peritoneal fluid is clear and colourless and a simple visual assessment can provide useful information. Pink or red discolouration or increased turbidity can suggest a serious underlying problem. Measurement of total nucleated cell count (TNCC) and total solid (TS) concentration can also be helpful.

Peritoneal fluid lactate concentration is really useful. An increased concentration suggests the possibility of ischaemia in the abdominal cavity. It is important to compare the peritoneal concentration to the systemic concentration, as the two values will be roughly equivalent in a normal horse.

A peritoneal lactate concentration greater than the systemic concentration is suggestive of ischaemia. Similarly, repeated peritoneal fluid sampling can be useful. Increasing concentrations of lactate, TNCC or TS suggests intestinal compromise.

Further treatment

The aim of performing further diagnostics is to allow provision of more targeted treatment. In some instances, these further tests will suggest the possibility of a surgical problem, and in these cases referral should be organised if possible.

Supportive care that can easily be administered in the field includes fluid therapy, analgesia, exercise and some forms of medication. Oral fluids can be an excellent way to help with mild dehydration or treat impactions within the large intestine.

In a 500kg horse, 4L to 6L of balanced electrolyte solution can safely be administered every few hours. IV fluids can also be administered using a large bore (12 to 14 gauge) catheter and giving set. Giving boluses of 5L to 10L of isotonic crystalloids can help correct deficits and restore circulating volume.

Light exercise in the form of walking, lungeing or, occasionally, riding can be very useful if you are concerned about the presence of gas distension or a mild colon displacement. In most cases of acute colic it is also sensible to suggest a brief period of fasting.

Specific medications (other than analgesia, which has already been briefly discussed) may also be indicated, but a full discussion is beyond the scope of this article. Examples include the use of phenylephrine for a suspected left dorsal displaced colon or psyllium for sand colic.

Summary

The key to successful treatment of any horse with colic is careful and, if necessary, repeated clinical examination. Basic diagnostic techniques can be useful to help a diagnosis or decision be reached about whether emergency treatment is necessary.

However, even in the absence of any specific findings, the presence of persistent abdominal pain should always prompt discussion about the possibility of a surgical problem.

References

- Busoni V, De Busscher V, Lopez D, Verwilghen D and Cassart D (2011). Evaluation of a protocol for fast localised abdominal sonography of horses (FLASH) admitted for colic, Vet J 188(1): 77-82.

- Cook VL and Hassel DM (2014). Evaluation of the Colic in Horses: Decision for Referral, Vet Clin of North Am: Equine Pract 30(2): 383–398.

- Espinosa P, Le Jeune S, Cenani A, Kass PH and Brosnan RJ (2017). Investigation of perioperative and anesthetic variables affecting short-term survival of horses with small intestinal strangulating lesions, Vet Surg 46(3): 345-353.

- Freeman S and Issaoui L (2013). Code red for colic: Decision-making for acute abdominal pain in the horse, Equine Vet Educ 25(5): 245–246.

- Le Jeune S and Whitcomb MB (2014). Ultrasound of the equine acute Abdomen, Veterinary Clin of North Am: Equine Pract 30(2): 353–381.