18 Aug 2021

Equine endocrine disorders

Nicola Menzies-Gow, MA, VetMB, PhD, DipECEIM, CertEM(IntMed), FHEA, MRCVS provides an overview of the two most common conditions affecting horses.

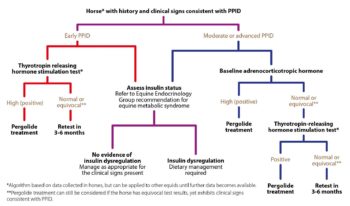

Figure 1. Algorithm for the detection of insulin dysregulation (ID).

Two endocrine disorders commonly affect the horse – namely equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) and pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID).

EMS is a collection of risk factors for endocrinopathic laminitis. Insulin dysregulation (ID) is the central feature of EMS and additional features include obesity (generalised or regional), cardiovascular changes and adipose dysregulation. Diagnosis of EMS centres on demonstration of ID using basal and/or dynamic tests. Management consists of dietary modification, exercise and use of pharmacologic agents.

PPID is an age-related progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterised by excessive production of the hormones normally produced by the pituitary pars intermedia due to loss of the hypothalamic dopaminergic inhibition. Diagnosis of PPID is based on the signalment, clinical signs and the results of further diagnostic tests. The risk of laminitis in animals with PPID appears to be increased in the subset of animals with ID. Management consists of pharmacologic therapy to replace the lost inhibition and dietary modification in the subset of animals with ID.

Two endocrine disorders commonly affect the horse – namely equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) and pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID).

EMS

EMS is a collection of risk factors for endocrinopathic laminitis. The key central and consistent feature of EMS is insulin dysregulation (ID) that may manifest as any combination of basal (resting) hyperinsulinaemia, an excessive insulin response to an oral or IV carbohydrate challenge and/or tissue insulin resistance.

Further inconsistent features of EMS comprise obesity, which may be generalised or regional; cardiovascular changes, including increased blood pressure, heart rate and cardiac dimensions; and adipose dysregulation manifesting as abnormal plasma adipokine concentrations, including hypoadiponectinaemia and hyperleptinaemia.

How does EMS cause laminitis?

It is now well established that hyperinsulinaemia induces laminitis in horses. Field-based studies have shown an association between hyperinsulinaemia, or other components of ID, and laminitis – and experimental studies demonstrated that laminitis can be induced by 48 to 72 hours of insulin infusion in ponies and horses.

However, exactly how hyperinsulinaemia causes laminitis remains to be determined. Theories including glucose deprivation, glucotoxicity, matrix metalloprotease upregulation and increased blood flow-induced hyperthermia have been disproven.

Current theories include endothelial dysfunction resulting in vasoconstriction, inappropriate signalling via binding of insulin to insulin-like growth factor receptors, and gut microbiota and gut permeability changes; however, these have yet to be definitively proven.

How does the insulin dysregulation occur in EMS?

The exact mechanism underlying ID in EMS remains to be determined. Evidence exists of a role for:

Genetics

Horses with EMS are often considered to be “good doers” or “easy keepers” and genes contributing to this phenotype are likely to be advantageous for survival in the wild during periods of famine by enhancing feed efficiency.

Initial research found that the prevalence of laminitis was consistent with the action of a major gene or genes expressed dominantly, but with reduced penetrance attributable to sex-mediated factors, age of onset and further epigenetic factors.

More recently, genome-wide association studies using Arabian horses, Welsh ponies and Morgan horses have identified several candidate genes that were associated with relevant traits, including height and insulin, triglyceride and adiponectin concentrations. This is an area of ongoing research.

Epigenetics

The environment in utero will influence the foal later in life. Certain genes will get switched on or off depending on the nutritional status of the mother, which then influence the offspring later in life. Both maternal over and undernutrition appear to increase the risk of obesity, and of being metabolically unhealthy later in life.

Microbiome

The gastrointestinal microbiome influences metabolism, endocrine signalling and the immune system in humans. For example, perturbations of the faecal microbiome in humans and mice have been associated with alterations in insulin secretion and sensitivity, incretin action and obesity – that is, a microbe-gut-endocrine axis.

Horses with EMS have been shown to have a decreased gastrointestinal microbial diversity and differences in community structure compared to control animals.

Obesity

Adipose tissue is the largest endocrine organ in the body, producing an array of hormones with normal physiological roles. Obesity results in adipose dysregulation such that the production of some hormones is increased (for example, leptin) and others is decreased (for example, adiponectin). Some of the affected hormones increase or decrease insulin sensitivity.

Diet

Diets high in non‑structural carbohydrate will reduce insulin sensitivity and adiponectin sensitivity compared to forage or fat-rich diets.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are found in numerous commercially produced compounds, including organochlorine pesticides such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane and as by‑products during synthesis of various chlorophenols and herbicides. They tend to be polychlorinated, lipophilic and persist in the environment.

Exposure to EDCs is associated with metabolic syndrome, obesity and type-two diabetes in humans. EDCs have been shown to be present in horse plasma, and animals living within a short radius of superfunds (chemical dump sites in the US) appear to be at an increased risk of EMS.

Clinical signs

Laminitis is the primary clinical consequence of EMS. However, horses with EMS might also be at risk of further problems including hyperlipaemia, and critical care-associated metabolic derangements such as hyperglycaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of EMS is based on demonstration of ID (Figure 1). Additional tests for the assessment of horses with EMS include measurement of circulating concentrations of the adipokine adiponectin and triglycerides.

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnoses for EMS are:

- Laminitis from other causes – laminitis associated with ID may also arise in association with glucocorticoid administration and PPID. Additionally, non-endocrinopathic causes of laminitis include sepsis-associated and supporting limb laminitis. However, it should be remembered that EMS may serve as a contributory factor in laminitis resulting from any other origin.

- Excessive adiposity without ID – adiposity is not inextricably linked with ID and it is possible for an individual horse or pony to have excessive fat depots without the concurrent presence of ID or EMS. Therefore, it is vital to demonstrate the presence of ID in an overweight animal before a diagnosis of EMS is made.

Management

The management of EMS consists of dietary modification, exercise and the short-term use of pharmacologic agents in some cases.

Diet

Dietary modification recommendations depend on whether the animal is obese or lean.

- Obese animals

Obesity is managed primarily via energy restriction through limiting intake. An ideal target for weight loss is 0.5% to 1% of body mass (BM) weekly. A daily forage allowance of 1.25% to 1.5% of actual BM as dry matter intake (DMI) or 1.4% to 1.7% of actual BM as fed is widely recommended.

In horses with weight loss resistance, a further forage restriction to 1% BM as DMI or 1.15% BM as fed may be considered if appropriately monitored. Grains or cereal‑based feeds should be excluded due to their high non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) content and high-fat feeds should be avoided due to their high energy content.

The nutrient composition of the forage should be determined where possible and hays with low NSC content (less than 10%) are recommended to limit postprandial insulin responses. Soaking for at least 60 minutes in cold water is advised to reduce the NSC content of the hay if necessary – and as forages can be low in protein, and mineral and vitamin leaching occurs after soaking, these nutrients must be balanced by low-calorie supplements to cover requirements. Haylage should be avoided if possible due to greater insulin responses and palatability compared to hay.

During the initial 6 to 12 weeks of dietary restriction, pasture access should be prevented, as even partial access is very difficult to quantify. However, successful long-term management of EMS cases can still include some grazing provided the ID – especially assessed by the insulin response to oral carbohydrates or grazing – is under control and that grazing is carefully controlled.

The use of dietary supplements such as cinnamon, magnesium and chromium to facilitate weight loss or to improve ID is popular, but their efficacy remains questionable or unproven.

- Lean animals

Lean animals should be fed a low glycaemic diet to minimise the postprandial insulin response. The diet should be based on forage with a low (ideally less than 10%) NSC content and have additional calories provided in the form of fat (for example, vegetable oil) and high-quality fibre such as beet pulp.

A low-calorie vitamin, mineral and protein ration balancer should be fed as required.

Exercise

Exercise has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in people; however, studies in horses have shown variable results. Exercise should only be considered in animals without current laminitis and should be gradually increased based on fitness. The optimal exercise regime has yet to be determined, but suggestions are:

- Previously laminitic animals: low-intensity exercise on a soft surface (fast trot to canter) for greater than 30 minutes, greater than 3 times per week.

- No previous laminitis: low to moderate-intensity exercise (canter to fast canter) greater than 5 times per week for greater than 30 minutes.

Pharmacologic agents

Pharmacologic agents should only be used in the short term (three to six months) in animals that do not respond to management changes alone.

Metformin is the commonest drug prescribed for managing ID in horses. Doses range from 15mg/kg to 30mg/kg given two to three times daily by mouth, and it is recommended that the drug is ideally administered 30 to 60 minutes prior to feeding. The oral bioavailability is extremely poor, and the drug does not appear to improve insulin sensitivity; however, it may have a beneficial effect through blunting of postprandial increases in glucose and insulin concentrations.

Levothyroxine (0.1mg/kg by mouth once a day) may be used in obese animals to accelerate weight loss through increasing the metabolic rate, but must be used in conjunction with diet and exercise changes.

Sodium-glucose co-transport 2 inhibitors, such as velagliflozin or canagliflozin, are used in the treatment of type-two diabetes mellitus in humans and have been shown to significantly decrease blood insulin concentrations in horses. They should be reserved for horses with severe ID affected by laminitis and the owner has sufficient resources for expensive medical treatment.

PPID

Equine PPID is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease with loss of dopaminergic (inhibitory) input to the melanotropes of the pituitary pars intermedia, which appears to be associated with localised oxidative stress and abnormal protein (α-synuclein) accumulation. However, the exact cause remains unknown. The consequent dysfunction of this region results in hyperplasia of this area of the gland and overproduction of pars intermedia-derived hormones; eventually the area undergoes adenomatous change.

How does PPID cause laminitis?

The risk of laminitis is greatest in the subset of animals with PPID that have ID. The mechanism by which PPID causes ID has yet to be determined; however, it is postulated that some of the pars intermedia hormones antagonise insulin – for example, β-cell tropin, which is a breakdown product of corticotropin-like intermediate peptide.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of PPID is based on the signalment, clinical signs and further diagnostic test results.

Signalment

The condition is seen in older animals; the average age in retrospective case series ranges from 18 to 23 years. However, it should be noted that the disease is recognised in animals younger than this, with the youngest reported case being in a 7-year-old animal. Therefore, the age of the animal – and, therefore, the likelihood of PPID being a true diagnosis – should be considered before further diagnostic testing is undertaken.

Clinical signs

Early

- Change in attitude/lethargy

- Decreased performance

- Regional hypertrichosis

- Delayed hair coat shedding

- Loss of topline muscle

- Abnormal sweating (increased or decreased)

- Infertility

- Desmitis/tendonitis

- Regional adiposity

- Laminitis

Advanced

- Dull attitude/altered mentation.

- Exercise intolerance

- Generalised hypertrichosis

- Loss of seasonal hair coat shedding

- Topline muscle atrophy

- Rounded abdomen

- Abnormal sweating (increased or decreased)

- Polyuria/polydipsia

- Recurrent infections

- Dry eye/recurrent corneal ulcers

- Infertility

- Increased mammary gland secretions

- Tendon and suspensory ligament laxity

- Regional adiposity (bulging supraorbital fat)

- Laminitis/recurrent sole abscesses

The clinical signs associated with PPID can be roughly divided into those that are seen early in the disease and those that are associated with advanced disease (Panel 1).

Some of the clinical signs associated with PPID are often mistaken by owners as changes associated with ageing. Therefore, owners recognising these signs may not regard them as important enough to seek veterinary advice and animals with PPID may go undetected.

However, it has also been shown that owners are better at detecting hypertrichosis compared to a veterinary clinical examination. Therefore, the historical information provided by the owner is of importance, as well as a detailed clinical examination, to detect the clinical signs associated with PPID.

Further diagnostic tests

No ideal further diagnostic test for equine PPID exists; however, plasma basal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) concentrations and the ACTH response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone are currently thought to be the most appropriate tests available (Figure 2; Table 1).

Additionally, it is recommended that tests to assess for ID are simultaneously performed (Figure 1), as ID occurs in a subset of animals with PPID, and appears to be associated with an increased risk of laminitis and a worse prognosis. Appropriate tests for ID include measurement of basal serum insulin concentration, an oral sugar and the insulin response test.

Treatment

Not all owners will elect to treat the disease specifically, depending on which clinical signs are present and how severe they are in an individual animal. The clinical signs can be managed individually – for example, clip excess hair, treat secondary infections, alter the diet to gain or lose weight and treat laminitis.

Where medical therapy is employed, the treatment of choice is the dopamine agonist pergolide (initial dose is 2mg/kg by mouth once a day; Figure 2), which is licensed for the treatment of this condition in horses in the UK. It is reportedly effective in 65% to 80% of cases. The serotonin antagonist cyproheptadine does not appear to be any more effective than non-pharmacological management, but can be used in addition to pergolide in refractory cases.

Normalisation or improvement of endocrine tests can be used to monitor the response to therapy starting 30 days after initiation of pergolide treatment; alternatively, improvement in the clinical signs can be used alone or in conjunction with the laboratory response (Panel 2). Lifelong drug therapy and/or management of the clinical signs is required as all the available drugs will only help control the clinical signs, but not result in a cure. Despite this, many horses continue to have a good quality of life for a number of years.

- Some drugs are used under the cascade.

- Figures, panels and tables have been recreated from the Equine Endocrinology Group (https://bit.ly/3xa1ufA).

Panel 2. Treatment and monitoring strategies

- Adequate laboratory response with good clinical response

If test results are normal at recheck and clinical signs have improved or are stable, the dosage is held constant and the patient is placed on a six-monthly recheck schedule, with one appointment occurring in the fall season. This allows assessment of the patient during the seasonal increase in adrenocorticotropic hormone concentration and ensures that treatment is adequate during this period. - Adequate laboratory response with poor clinical response

If test results are normal at recheck, but recurrence or development of new problems has occurred (that is, laminitis, bacterial infection or weight loss) then reassess the patient for additional medical problems – including insulin dysregulation – before assuming that an increase in pergolide dosage is required. - Inadequate laboratory response with good clinical response

If test results are abnormal at recheck, yet the patient is responding well clinically, the dosage can be held at the same level or increased, according to the veterinarian’s preference. This may be observed more commonly when testing is performed in fall months. - Inadequate laboratory response with poor clinical response

If test results remain abnormal at recheck and the patient is not responding well clinically, increase the daily dosage by 0.5mg to 1mg for a 500kg horse (1mcg/kg/day to 2mcg/kg/day) and recheck after two to four weeks. Treatment strategies used by the group for refractory cases include gradually increasing the pergolide dosage to 3mg for a 500kg horse (6mcg/kg) daily and adding cyproheptadine (0.25mg/kg orally twice daily or 0.5mg/kg once daily) or gradually increasing the pergolide dosage up to 5mg for a 500kg horse (10mcg/kg) daily.

Latest news