20 Oct 2020

Eyelid tumours in dogs and cats – part 1

Figure 1. The meibomian gland orifices of the canine lower eyelid localised within the shallow grooved area called the grey line.

This review provides a clinical and surgical approach to the most frequently diagnosed and most important eyelid neoplasms in dogs and cats.

The article is divided into three parts. Part one discusses the anatomy and examination of the eyelids in dogs and cats, then focuses on the clinical appearance, histological features and treatment of common canine eyelid tumours.

Part two covers the most common feline eyelid tumours. A detailed description of basic and more advanced surgical procedures to address eyelid tumours in dogs and cats will be described in part three.

A brief overview of the clinical and functional anatomy of the eyelid is important for practical management of common tumours.

The eyelid consists of an outer layer of skin, a tarsal plate, smooth (Müller’s muscle) and striated muscle (for example, the orbicularis oculi and the levator palpebrae superioris), and an inner conjunctival lining.

The medial and lateral canthi, both supported by tendons, differ concerning composition and strength. The medial canthal tendon is a distinct fibrous band attached to the periosteum of the frontal bone, whereas the lateral canthal tendon is a musculofibrous band under the conjunctiva and connects the retractor anguli oculi lateralis muscle to the orbital ligament.

The orbicularis oculi muscle enables the closing phase of blinking, whereas the levator palpebrae superioris and levator anguli oculi medialis – and other superficial facial muscles – function to open the upper eyelid, and the malaris muscle opens the lower eyelid.

With regards to muscular innervation (Table 1), the palpebral branch of the auriculopalpebral nerve of the facial nerve (cranial nerve [CN] VII) innervates the levator anguli oculi medialis, retractor anguli oculi lateralis and orbicularis oculi muscles. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle is innervated by the oculomotor nerve (CN III). The malaris muscle is innervated by the dorsal buccal branch of the facial nerve (CN VII). Müller’s muscle is under sympathetic control. The main sensation of the canine eyelid skin is provided by several branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V).

| Table 1. Function and innervation of the eyelid muscles. The palpebral nerve of the auriculopalpebral nerve and the dorsal buccal nerves are branches of the facial nerve (cranial nerve [CN] VII; Evans and de Lahunta, 2013; Maggs, 2013) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Muscle | Function | Innervation |

| Orbicularis oculi | Closing the eyelids | Palpebral nerve (CN VII) |

| Levator palpebrae superioris | Opening the upper eyelid | Oculomotor nerve (CN III) |

| Müller’s | Opening the upper eyelid, protruding the eyeball | Sympathetic nervous system |

| Levator anguli oculi medialis | Opening the upper eyelid | Palpebral nerve (CN VII) |

| Retractor anguli oculi lateralis | Drawing the lateral palpebral angle caudally | Facial nerve (CN VII) |

| Malaris | Opening the lower eyelid | Dorsal buccal nerve (CN VII) |

The blood supply of the eyelids is provided by medial and lateral palpebral arteries of the superficial temporal artery, branches of the external ethmoidal artery, branches of the malaris artery and a branch of the infraorbital artery. The angularis oculi vein provides venous drainage. The lymphatic drainage of the eyelids is provided by the parotid and mandibular lymph nodes.

Unlike dogs, cats do not have eyelashes in the upper eyelids; instead, the first row of hairs fulfils much the same function. The lower eyelid is free of eyelashes in both species.

Each eyelid contains approximately 20 to 40 modified sebaceous meibomian glands, which open along the eyelid margin at a distinct grooved area called “the grey line” (Figure 1). This groove and the Meibomian gland openings are important surgical landmarks.

Meibomian glands produce meibum, which forms the outer lipid layer of the tear film. The eyelid glands of Moll and Zeis – which are modified sweat glands and modified sebaceous glands, respectively – also contribute to tear film.

The eyelid margin plays an important role in tear film distribution and ocular surface health. The upper and lower eyelid lacrimal puncta are involved in tear drainage via the lacrimal apparatus.

Examination

An important aspect of the clinical examination is to distinguish eyelid tumours from conjunctival neoplasms, which, without effective therapy, tend to be more locally invasive, often recur and can metastasise – for example, melanoma (Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013).

Distant examination is essential to assess position of the globe, symmetry of eyelid conformation, periocular skin changes, epiphora, photophobia and blepharospasm. This should be followed by vision assessment, neuro‑ophthalmic examination, Schirmer tear test 1 and tonometry.

“Hands on” examination should start with palpation of the eyelids, orbit and globe retropulsion, followed by assessment of the tumour – including its extent by a naked eye then with magnification.

If the neoplasm is localised medially within the eyelid, the lacrimal punctum should be identified, if possible.

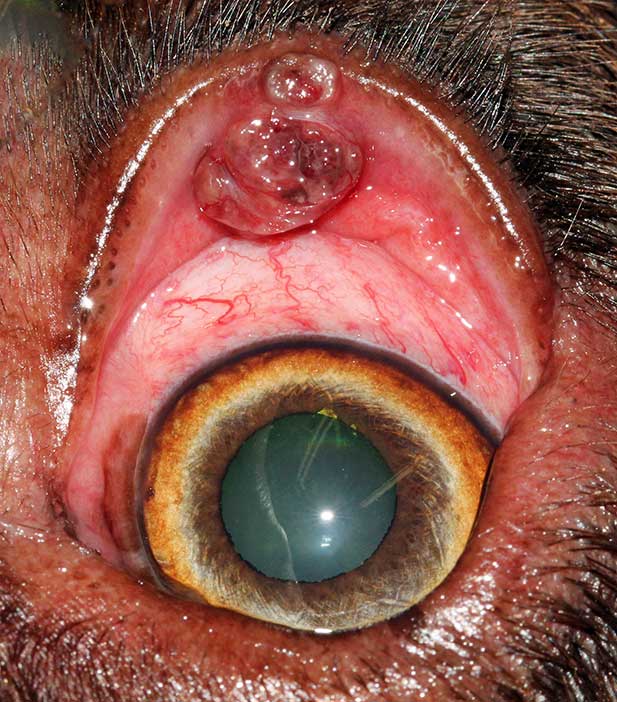

It is important to evert the eyelid margin to examine the palpebral conjunctiva, as the external eyelid lesion is not always representative of the entire tumour (Figures 2 and 3).

Eyelid tumours can cause conjunctivitis, keratitis or corneal ulceration, so careful examination of ocular surface – including application of fluorescein dye – is required, which, if present, may require additional treatment.

Physical examination is essential to identify evidence of metastatic disease or systemic neoplastic condition.

Although some individual eyelid tumours have typical characteristics and clinical features, only histological examination of incisional/excisional tissue biopsy specimens will confirm the diagnosis (Maggs, 2013).

Cytological examination can be helpful to differentiate, for example, a mast cell tumour from meibomian gland neoplasm or histiocytoma; or squamous cell carcinoma from atopic blepharitis (Figure 4) prior to further treatment and/or surgical planning.

Common eyelid tumours in dogs

Between 73% and 88% of eyelid neoplasms in dogs are reported to be benign (Krehbiel and Langham, 1975; Roberts et al, 1986).

Eyelid neoplasms occur most commonly in dogs older than eight years of age with the exception of papillomas and histiocytomas, which occur in young dogs (Krehbiel and Langham, 1975; Roberts et al, 1986; Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013).

The most common canine eyelid tumours are described below, in order of decreasing frequency (Roberts et al, 1986).

Meibomian gland adenomas/epitheliomas

Meibomian gland adenomas and epitheliomas (Figures 5 to 9) are the most commonly diagnosed eyelid tumours, accounting for between 29% and 60% of all canine eyelid tumours (Krehbiel and Langham, 1975; Roberts et al, 1986). They originate from the Meibomian gland and are benign.

The term adenoma is used to refer to neoplasms with a predominance of well‑differentiated glandular secretory cells, whereas the term epithelioma is used to describe glandular tumours composed of undifferentiated basal cells.

Meibomian gland adenomas/epitheliomas clinically present as proliferative, lobulated, pink, grey or pigmented and friable masses at the eyelid margin. The tumour commonly blocks the meibomian duct, which can lead to glandular rupture, peritumoral lipogranulomatous inflammation and artificially increase the size of the tumours (Labelle and Labelle, 2013). The tumours may also erupt through conjunctiva just behind the eyelid, become ulcerated or be associated with bleeding (Figure 10).

The local irritation can cause blepharospasm, epiphora, conjunctival hyperaemia, corneal vascularisation and pigmentation.

Complete evaluation of the extent of these tumours requires eversion of the eyelid margin in most cases (Labelle and Labelle, 2013).

In the early stages, this tumour appears as a small mass, which can be removed via a simple wedge or four‑sided resection. Once large, blepharoplasties (advanced eyelid plastic procedure using a skin graft) are usually required.

A margin of one meibomian gland opening, or 1mm beyond the tumour margins, is usually sufficient to avoid local recurrence because the growth of these tumours is expansile and not infiltrative (Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013). A risk of local recurrence exists after incomplete resection surgery or cryosurgery (Roberts et al, 1986; Maggs, 2013).

Meibomian gland adenocarcinomas are rare.

Cutaneous melanocytomas

Cutaneous melanocytomas (Figure 11) are the second most common benign eyelid tumours, accounting for 17% of all canine eyelid tumours (Roberts et al, 1986).

They usually present as a solitary pink to brown-black mass, which can involve the outer skin of the eyelid or the eyelid margin (Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013).

Melanocytomas can be successfully excised with at least 1mm to 2mm margins. Following marginal excision, the surgical site can also be treated with adjuvant cryotherapy to improve local control (Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013).

CO2‑mediated laser ablation has also been described (Esson, 2015); however, studies concerning outcome are limited.

Malignant melanomas (Figure 12) in the eyelid are uncommon, but it is important to recognise them because they are locally aggressive, and can spread to local lymph nodes and distant sites (Esson, 2015).

The diagnosis of malignant melanoma is based on histological features, including nuclear atypia and high mitotic count (more than 3 mitoses in 10 high‑power fields are indicative of malignancy; Smedley et al, 2011).

Another common feature is junctional activity, which is the proliferation of neoplastic melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, and explains the extension of the tumour far beyond the clinically visible tumour margins (Dubielzig et al, 2010; Smedley et al, 2011).

The treatment of choice for malignant melanoma is wide surgical excision often requiring reconstructive surgery blepharoplasty (Esson, 2015). Staging, including evaluation of the local draining lymph node and the lungs, should be routinely performed before embarking in aggressive surgery.

Local recurrence would be expected when the margin of excision is incomplete (Featherstone, 2013), but adjuvant strontium plesiotherapy can be used to increase the chance of long‑term local control.

Papillomas

Historically, papillomas have been considered as the third most common benign eyelid tumours, accounting for about 10% to 20% of all canine eyelid neoplasms (Krehbiel and Langham, 1975; Roberts et al, 1986), but nowadays they are rarely diagnosed.

This could potentially be because fewer dogs live in a rural environment and they have, in general, a good care.

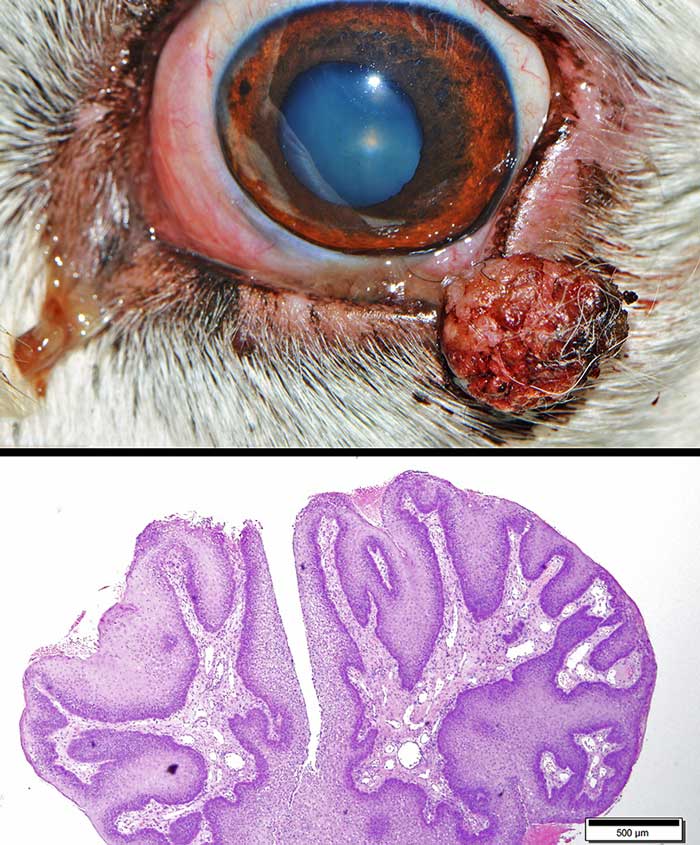

Papillomas are superficial, pedunculated and have a typical verrucose appearance. They can be caused by papillomavirus infection (viral papillomas) and be associated with oral or generalised cutaneous papillomatosis (Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013).

Viral papillomas (Figure 13) are more commonly seen in young dogs or immunocompromised adults. Spontaneous tumour regression is often seen with the development of appropriate immune response.

If no evidence of viral infection exists on histology (such as inclusion bodies and koilocytes), papillomas can be classified as squamous or reactive (Figure 14); the latter are associated with inflammation or can be present on the surface of meibomian gland tumours.

Regardless of the type of papilloma, excision should be considered if the lesion causes corneal irritation (Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013; Esson, 2015).

Adjuvant cryosurgery can be used to decrease the risk of recurrence after marginal excision (Stades and van der Woerdt, 2013).

Histiocytomas

Histiocytomas are usually solitary benign eyelid lesions (Figure 15). Young dogs are more often affected than adult or senile canine patients.

Histiocytomas are usually raised, round, pink, hairless lesions (Manning, 2014; Maggs, 2013).

Immune-mediated regression is common; however, removal may be required if the tumour becomes ulcerated, inflamed, or does not regress within three months (Manning, 2014; Maggs, 2013; Esson, 2015).

Mast cell tumours

Mast cell tumours (MCTs; Figure 16) are the most common malignant skin tumours in the dog and can affect the eyelids.

MCTs typically present as a solitary mass and can be alopecic, erythematous, oedematous or ulcerated. The diagnosis can be easily obtained with fine needle aspiration biopsy.

An anti-inflammatory dose of oral corticosteroid can be administered for a few days prior to surgery to reduce the size the tumour (Stanclift and Gilson, 2008). Pre‑surgical antihistamines can also help reduce the effect of mast cell degranulation associated with manipulation of the tumour during surgery (Esson, 2015).

Staging prior to surgical excision is recommended and, in particular, aspiration of the local draining lymph node (for eyelid tumours the ipsilateral mandibular lymph node; Esson, 2015).

Two histological grading schemes are available: the Patnaik system (Patnaik et al, 1984) and the Kiupel system (Kiupel et al, 2011).

The Patnaik system classifies MCTs in three grades: grade I tumours are associated with a favourable prognosis after complete resection, while grade III tumours are locally aggressive and finding metastatic disease on presentation is common. Predicting the behaviour of grade II MCTs is more difficult because only approximately 20% are aggressive.

The Kiupel grading scheme, which divides MCTs as low grade or high grade, was developed to obviate the problem posed by grade II MCT and to improve reproducibility of the grade assignment between pathologists.

The present recommendation for resection of MCTs is 2cm of lateral margin and one fascial plane in the deep margin. As this recommendation is not applicable to the eyelid, local adjuvant treatment – such as strontium plesiotherapy, brachytherapy or external beam radiation – should be considered to improve local control after incomplete removal (Figure 17).

Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for high‑grade tumours to decrease the risk of metastatic dissemination. Tyrosinase inhibitors (c-KIT inhibitors) are indicated for macroscopic non-resectable MCTs as a palliative treatment (Featherstone, 2013).

Other tumours

The canine eyelids can be affected by many other canine skin tumours, but these are much less common than those described in this article.

Examples include tumours of hair follicle origin, apocrine adenoma, granular cell tumour, fibrosarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 18) and mesenchymal hamartoma (Kafarnik et al, 2010; Lu and Dubielzig, 2012).

Epitheliotropic lymphoma (Figure 19) can also affect the eyelid, but most commonly is only part of a more generalised disease (Manning, 2014). Typical findings include thickened, irregular to nodular, exfoliative, proliferative and/or ulcerative blepharitis and conjunctivitis, which may be associated with depigmented mucocutaneous lesions (Esson, 2015).

Chemotherapy or radiotherapy can be used to try to control local and systemic disease (Esson, 2015; Berlato et al, 2012). The prognosis is, however, considered guarded, with a survival time after diagnosis that ranges from a few months to two years; solitary lesions have a better prognosis (Fontaine et al, 2009).

Related clinical resources

Diagnosing arthritis in cats

Clinical Assist