6 Apr

Eyelid tumours in dogs and cats – Part 2

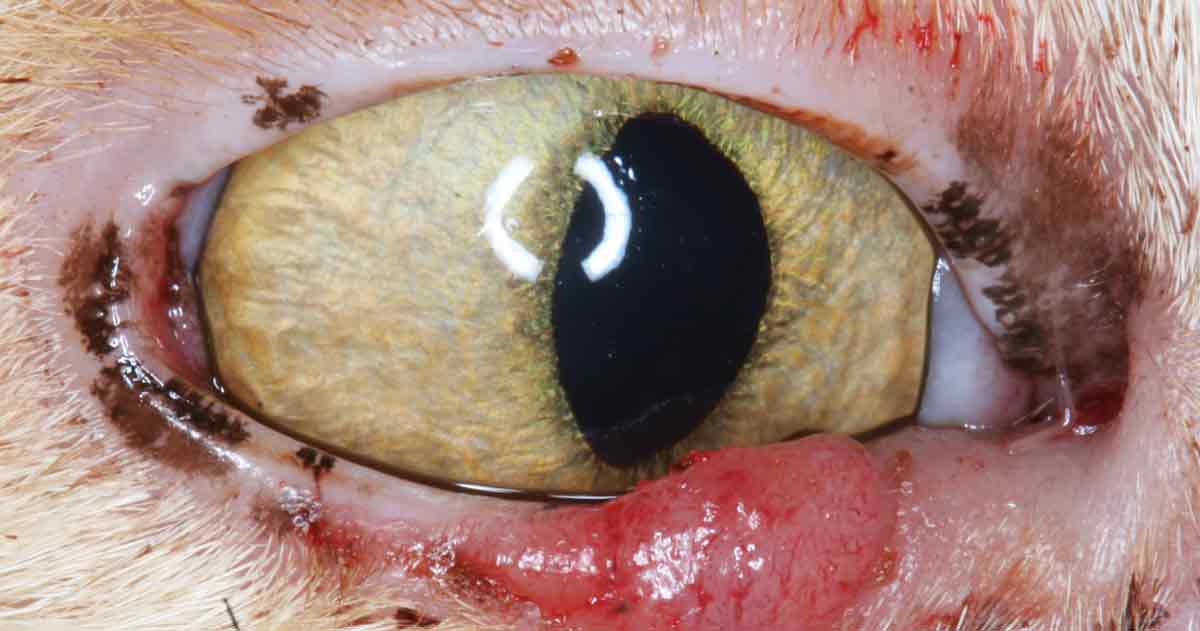

Figure 1. Erosive medial canthal and medial upper eyelid squamous cell carcinoma in the right eye.

This review provides a clinical and surgical approach to the most frequently diagnosed and most important eyelid neoplasms in dogs and cats.

The article is divided into three parts. Part one (VT50.43) discussed the anatomy and examination of the eyelids in dogs and cats, then focused on common canine eyelid tumours.

Here, in part two, clinical appearance, histological features and treatment of common feline eyelid tumours will be discussed. A detailed description of basic and more advanced surgical procedures to address eyelid tumours in dogs and cats will be described in part three.

Feline eyelid tumours are more likely to be malignant than benign and are infrequent compared to dogs (McLaughlin et al, 1993; Stiles, 2013; Table 1).

Eyelid neoplasms occur most commonly in cats older than 10 years of age (Manning, 2002). They are listed below in order of decreasing frequency (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009).

| Table 1. Summary of the most common eyelid tumours of the dog and cat. For more details on canine eyelid tumours, please refer to part one | ||

|---|---|---|

| Canine | Feline | |

| Meibomian gland adenoma/epithelioma | The most common, benign, excellent prognosis | Uncommon |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Rare | The most common, locally invasive, metastasis may occur, guarded prognosis |

| Melanocytic tumour | Second most common, usually benign, good prognosis when completely excised | Rare, usually malignant, guarded prognosis |

| Mast cell tumour | Common, prognosis varies with histological grade; appropriate surgical margins +/− adjunctive therapy are main stain | Second most common, prognosis varies with histotype, usually good prognosis even with incomplete excision |

| Papilloma | Nowadays rare (third most common in the literature), benign, surgical excision and cryotherapy associated with good prognosis | Uncommon |

| Histiocytoma | Moderately common, benign, affecting most commonly young dogs, may spontaneously regress | Uncommon |

Squamous cell carcinomas

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs; Figures 1 and 2) are the most common eyelid neoplasm in cats, accounting for 28% to 65% of cases (McLaughlin et al, 1993; Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009). The average age of cats with SCCs is 12.4 plus or minus 3.3 years (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009).

SCCs clinically present as a raised or depressed lesion with an ulcerated, crusty surface either on or just adjacent to the eyelid margin. Exposure to sunlight is a contributory factor and a predilection exists for white cats with poorly pigmented eyelids (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009; Murphy, 2013).

These tumours are generally erosive and locally aggressive, which may extend into the conjunctiva, globe and orbit, and consequently cause exophthalmos and exposure keratitis; intracranial extension has also been reported (Esson, 2015; Diehl et al, 2018). Metastases to regional lymph nodes has been reported to occur with advanced stage of disease (Wilcock et al, 2002; Diehl et al, 2018). In the uncommon event of distant metastatic spread, the lung is the first distant organ affected (Diehl et al, 2018).

SCCs can result in local inflammation and blepharitis, and conjunctivitis can make it difficult to identify tumour margins (Maggs, 2013). The aim of surgical treatment of adnexal or periorbital SCCs is maintaining normal eyelid appearance and function, and preservation of the globe. Depending on the size of the lesion, wide surgical excision is often curative (Stiles, 2013).

As a complete excision requires margins of up to 5mm, it may involve extensive grafting procedures (Murphy, 2013). Options include the lip to lid flap, and various rotational and advancement skin flaps (Doherty, 1973; Pavletic, 1982; Hunt, 2006; Whittaker et al, 2010). Excision of extensive lesions may require a caudal auricular axial pattern flap to close the surgical defect (Stiles et al, 2003).

Effective treatment options for superficial lesions, or when surgical options are limited, include strontium-90 plesiotherapy (as sole therapy for superficial lesions no deeper than 3mm), radiotherapy, cryotherapy and photodynamic therapy (Stell et al, 2001; Hardman and Stanley, 2001; Stiles, 2013; Murphy 2013).

For cases with extensive adnexal and/or orbital invasion of SCCs, enucleation or exenteration, including advancement skin flap, should be considered (Stiles, 2013; Diehl et al, 2018).

Following complete excision, SCCs are reported to be significantly more likely to recur than mast cell tumours; the average survival time for cats with SCCs is 7.4 months plus or minus 2.5 months (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009).

Feline restrictive orbital myofibroblastic sarcoma

Important clinical differential of orbital invasive SCCs with adnexal involvement (OISCCAI) is feline restrictive orbital myofibroblastic sarcoma (FROMS), which can clinically present with similar features including keratitis and eyelid/third eyelid restriction and/or thickening (Diehl et al, 2018).

FROMS affect middle-aged to older cats with no sex or breed predisposition. FROMS can involve the surrounding orbital and facial tissues – including the lips, and oral and nasal cavities – and even the contralateral eye (Thomasy et al, 2013). Intracranial extension or metastasis of FROMS has not been reported as opposed to OISCCAI (Diehl et al, 2018).

Exophthalmos and/or resistance to retropulsion are reported as less common in OISCCAI cases compared to FROMS. On the other hand, an overt eyelid or orbital mass has appeared to be more common in OISCCAI cases compared to FROMS cases (Diehl et al, 2018).

Despite similar clinical features, OISCCAI and FROMS are histopathologically different; bland fusiform cells with minimal atypia characterise FROMS, whereas OISCCAI consists of pleomorphic epithelial cells (Bell et al, 2011). Positive immunohistochemical staining of the spindle cells for vimentin and smooth muscle actin can confirm the diagnosis of FROMS (Bell et al, 2011).

Limited literature has existed regarding treatment for patients with FROMS; however, despite various therapeutic options the prognosis is poor, and even with enucleation and exenteration, recurrence is common (Miller et al, 2000; Billson et al, 2006; Bell et al, 2011; Thomasy et al, 2013).

Mast cell tumours

Mast cell tumours (MCTs; Figure 3) are the second most common feline eyelid neoplasms, accounting for 26% of cases (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009). The average age at diagnosis is 6.5 years (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009). Most feline MCTs are solitary benign lesions. If the cat has, in addition to the eyelid MCT, another cutaneous MCT, the risk of internal organ involvement is higher; therefore, staging should be performed (Scott, 1980).

The clinical presentation of feline MCT varies from diffuse eyelid swellings to well-circumscribed ulcerative lesions, usually located on the outer skin of the eyelid. No histological grading system exists for feline MCT (Dubielzig et al, 2010) – instead the mitotic count is used as an indicator of malignancy (Lepri et al, 2003).

Based on morphological cell features, feline cutaneous/eyelid MCT can be subdivided into three histological subtypes:

- well-differentiated mastocytic

- pleomorphic mastocytic

- atypical – formerly referred to as histiocytic

The subtype pleomorphic mastocytic usually presents a more aggressive biologic behaviour, although further studies are needed to clarify the prognostic significance of the histological classification (Sabattini and Bettini, 2010; Blackwood et al, 2012). The atypical variants, or histiocytic, was initially described in young Siamese cats, with few cases of spontaneous regression documented in the literature (Miller et al, 1991).

In general, excision is usually curative and the rate of local recurrence of feline cutaneous MCTs is low (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009; Montgomery et al, 2010).

The study by Newkirk and Rohrbach has reported that most of the affected cats were still alive for at least six months to eight years after diagnosis and no recurrence was reported even when an incomplete surgical margin was achieved (Newkirk and Rohrbach, 2009). This is consistent with a more recent study specifically focused on periocular feline MCT that described a 5% recurrence rate of solitary tumours with incomplete surgical margins (Montgomery et al, 2010).

A study by Turrel et al (2006) has showed that the recurrence rate with strontium-90 irradiation therapy was even lower at 3%. Adjunctive therapy with strontium has been suggested if complete excision cannot be achieved (Montgomery et al, 2010). Rarely, feline cutaneous MCTs behave aggressively and metastasise (Buerger and Scott, 1987).

In the study by Montgomery et al (2010) on periocular feline MCT, metastatic disease involving peripheral lymph nodes or abdominal viscera was not detected in any cat and the median survival time of the study population was 945 days (Montgomery et al, 2010).

Peripheral nerve sheath tumours

Peripheral nerve sheath tumours (PNSTs; Figure 4) are spindle cell neoplasms arising from the neural sheath of the peripheral, cranial or autonomic nerves (Manning, 2002). The feline eyelid appears to be particularly at risk for developing PNSTs.

Feline eyelid PNSTs are usually locally infiltrative neoplasms, unlikely to metastasise; local recurrence is common (Hoffman et al, 2005; Montgomery et al, 2010). Wide margins of excision that may necessitate enucleation/exenteration may be required (Stiles, 2013). However, a recent study revealed that the combination of surgery and adjuvant plesiotherapy has been able to provide good local control with minimal toxicity (Berlato et al, 2016).

Apocrine cystadenomas

Apocrine cystadenomas (hidrocystomas) (Figure 5) are single or multiple benign cystic lesions derived from proliferation and dilation of the apocrine glands of Moll localised on the upper or lower eyelid (Manning, 2002).

Apocrine cystadenomas present as smooth, spherical, hairless lesions, typically dark blue or black (Montgomery et al, 2010). Persians are predisposed (Cantaloube et al, 2004).

Recurrence after surgical excision is common and adjunctive cryosurgery is recommended (Esson, 2015). Further treatment options include drainage or combination of tissue debridement and chemical ablation by the 20% trichloracetic acid (Yang et al, 2007).

Other rare eyelid neoplasms of cats include lymphomas, fibrosarcomas, haemangiomas, haemangiosarcomas and melanomas (Manning, 2002; Montgomery et al, 2010; Dubielzig et al, 2010).