6 Jul

Eyelid tumours in dogs and cats – part 3

This review – part three of a series – provides a clinical and surgical approach to the most frequently diagnosed and most important eyelid neoplasms in dogs and cats.

Part one discussed the anatomy and examination of the eyelids in dogs and cats. The remainder of part one, and part two were focused on common canine and feline eyelid tumours respectively. Here, a detailed description of basic and more advanced surgical procedures to address eyelid tumours, in dogs and cats, is provided.

Treatment should be tailored to the individual tumour type following systemic assessment of the patient.

Factors to consider prior to any therapy include malignancy, rate of growth, localisation, local invasiveness, presence of metastases, degree of corneoconjunctival irritation, and response to previous and current therapy (Maggs, 2013).

Eyelid tumours are mostly treated surgically, often with adjunctive therapy such as cryotherapy, brachytherapy, carbon dioxide laser therapy, photodynamic therapy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy or immune therapy.

Adjunctive therapy should always be considered if complete resection of the tumour is not possible to obtain (Maggs, 2013).

Surgical preparation for adnexal procedures

Head position of the patient should be supported using, for example, a vacuum-aided bead-filled cushion (Figures 1a and 1b).

Head loupes – headband system (Figure 2) or glass-mounted (2× to 6× magnification) – with an inbuilt source of illumination are advised.

A povidone-iodine aqueous solution (10ml of 1:50) diluted in sterile sodium chloride 0.9% should be used to flush the cornea and conjunctival fornices. Then sterile cellulose spears (Figure 3) soaked in the 1:50 povidone‑iodine solution are used to remove any mucus or debris. A minimum contact time of five minutes is required (Maggs, 2018).

After that, 10ml of sterile saline solution is used to flush out the antiseptic solution.

At the end, swabs soaked in a 1:10 povidone‑iodine solution are used to prepare the outer eyelid skin.

Surgical instruments

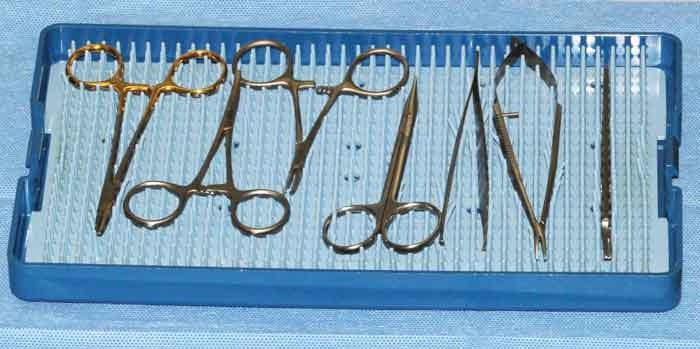

Surgical instruments should be kept in either plastic or steel surgical sterilisation trays (Figure 4).

A basic eyelid surgical kit (Figures 5a to 5d) should include the following instruments:

- eyelid speculum (eg, Castroviejo, Barraquer),

- Bennett’s cilia forceps

- chalazion Desmarres forceps

- Brown-Adson thumb tissue forceps

- fine rat tooth forceps

- Bard-Parker handle

- Beaver scalpel handle

- Derf needle holder

- Castroviejo (non-locking) needle holder

- straight and curved haemostats

- Steven’s tenotomy scissors

- Calipers (eg, Jameson and Castroviejo)

- Jaeger lid plate

- Nettleship’s dilator

- straight Metzenbaum scissors (Figure 6a)

- curette (Figure 6b)

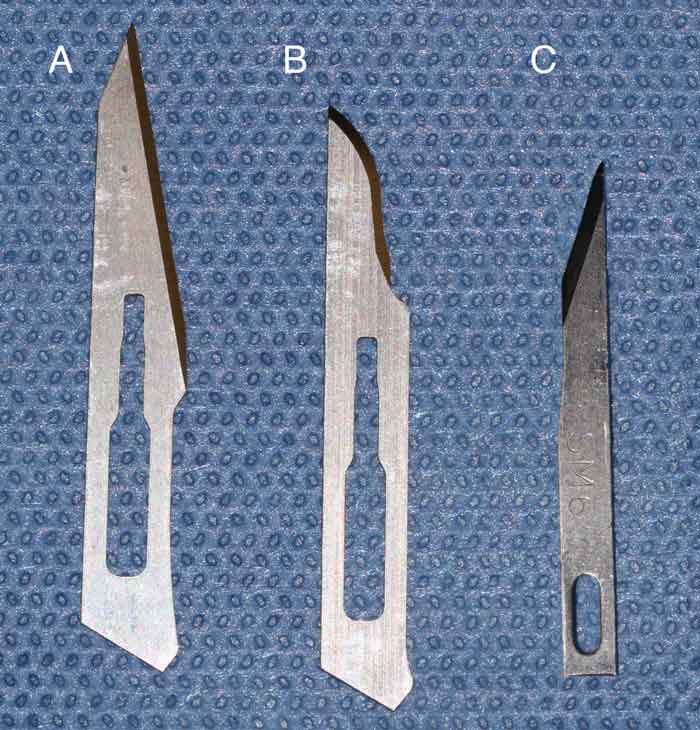

Disposables consist of biopsy punch (Figure 6c); adhesive and non-adhesive paper drapes; cellulose tipped spears or absorbent sticks (Figure 7); No.11 or No.15 Bard-Parker scalpel blades; and Beaver blades, for instance No.65 (Figure 8).

Surgical principles of eyelid surgery

Eyelid skin requires gentle handling, technique and fine instruments.

Surgical procedures depend on the site of the eyelid mass and the eyelid margin involvement. The upper lid is larger and more mobile than the lower lid, and it plays an important role in covering the cornea during blinking. Therefore, it is important for upper eyelid defects to be accurately repaired to maintain eyelid anatomy and function (Manning, 2002).

Resection of the lesion adjacent to, or involving, the medial canthus is more difficult as the skin is very tightly adhered to periorbital tissue (Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013; Figure 9).

Regarding the lacrimal puncta, the lower one should be preserved if possible to prevent epiphora (tear overflow) (Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013; Figure 10).

The lid margin is the most important area during blepharoplasty, and precise apposition of eyelid margins is required to avoid corneal and conjunctival damage (Figure 11).

Maintaining/restoring the conjunctival fornix will prevent disruption of tear collection and movement. Blunt dissection and tissue undermining should be minimal to avoid tissue damage, swelling and decreased blood supply to the lid (Gelatt, 2014).

Lid flaps and grafts have a tendency to contract postoperatively; therefore, they should be planned appropriately larger than the true size of the eyelid defect (Gelatt, 2014).

For precise surgical planning, a marker pen to outline the skin incision and calipers are used. The resection should be at least one meibomian gland orifice or 1mm beyond the margins of the tumour (Manning, 2002; Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013).

In feline squamous cell carcinoma, complete excision with margins up to 5mm is recommended (Murphy, 2013). The average length of the palpebral fissure when stretched by calipers is approximately 33mm in most medium to large-breed dogs (Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013). In canine, about a quarter of the eyelid length can be safely removed by a wedge excision, shaped either as V or four-sided defect (Figures 12a to 12d), to be able to achieve primary closure (Gelatt and Blogg, 1969; Gwin, 1980; Hamilton et al, 1999). When more than 25% of eyelid length is removed, blepharoplasty should be performed.

Furthermore, when 60% to 90% of the eyelid is involved, more extensive blepharoplasty procedures are required.

In cats where eyelids are more tightly apposed, blepharoplasty should be considered even for small defects (Gould and Carter, 2016).

Commonly used suture material for adnexal surgery is either absorbable (such as polyglactin) or non-absorbable (such as nylon), sized 6‑0 with a curved reverse cutting needle (Mitchell and Oliver, 2015). The authors prefer absorbable suture material as suture removal may require sedation, especially in cats.

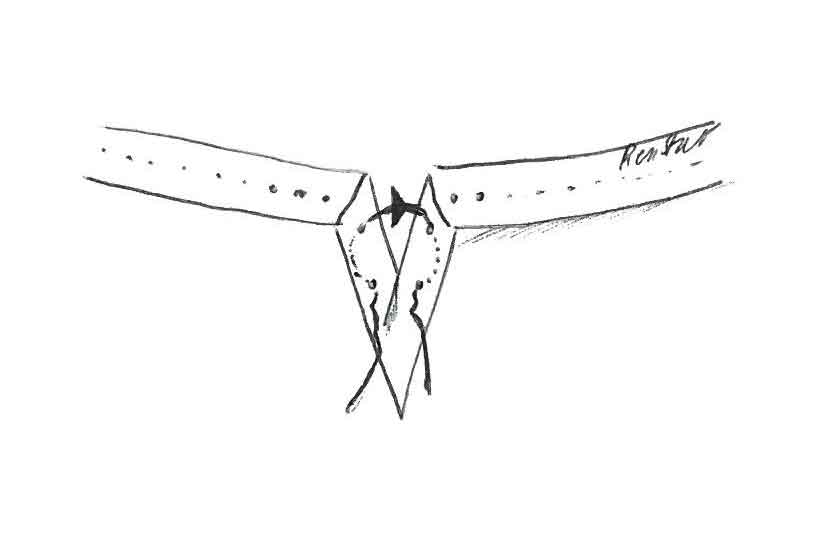

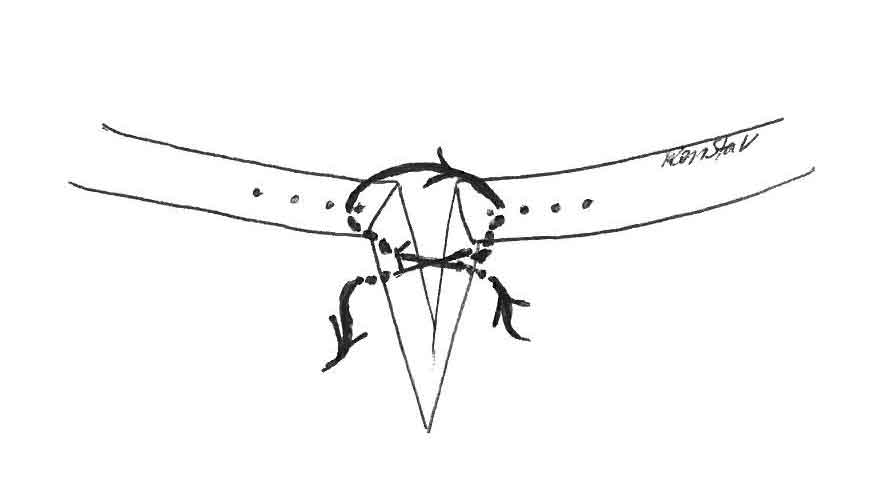

The resultant defect is closed in two layers, rather than one, to avoid a V notch at the eyelid margin. Two-layer suturing consisting of a tarsal plate suture (6/0, absorbable suture material) and a figure of eight suture (6/0, absorbable suture material) dictates not only good apposition, but also wound strength (Figures 13a and 13b).

Tarsal plate suturing will also reduce postoperative haemorrhage from wounded conjunctiva. The tarsal plate suture is followed by a simple, continuous suture, with the knots buried, to appose the tarsoconjunctival layer (6/0, absorbable suture material).

Very thin eyelids may be sutured with a figure of eight suture only. The eyelid muscle/skin is apposed with a simple, interrupted suture (6/0 non‑absorbable/absorbable suture material). The knot of a figure of eight suture should be directed away from the cornea.

Postoperative treatment consists of topical antibiotics (7 to 10 days) and systemic NSAIDs (3 to 5 days). Systemic antibiotics may be indicated for extensive procedures (Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013) or for patients that are difficult to treat topically. An Elizabethan collar is advised to prevent the patient from rubbing and possibly interrupting the surgical site (Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013).

Basic surgery techniques

Basic eyelid surgery techniques in cats and dogs (Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013) include:

- V/four-sided eyelid resection and primary closure of an eyelid defect after neoplasm excision from the upper or lower eyelid:

- A full–thickness excision of the mass with appropriate margins is performed.

- Free eyelid margin incisions are performed by a scalpel blade No.11 or No.15, or Beaver blade No.65.

- The incision is expanded as a V shape or four-sided shape on the outer eyelid skin. The V‑shaped excision is performed by oblique cutting of meibomian glands, whereas a four‑sided or house-shaped excision is created by rectangular cutting of the eyelids (Figures 9 and 12a to 12d).

- The tumour is then excised “en bloc” using Steven’s tenotomy scissors.

- The resultant defect is closed in two layers (a tarsal plate suture and a figure of eight suture) with absorbable 6/0 suture material, as previously described.

- Blepharoplasty (Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013): Blepharoplasty should be performed if primary closure of an eyelid margin defect is not possible by direct suturing.

- “House inverted-triangle” blepharoplasty (Figures 14 and 15):

- A one-step procedure, indicated for small upper and lower eyelid lesions.

- A full or partial excision of the mass with appropriate margins is performed.

- Removal of masses of 25% to 50% of the eyelid length; especially when the stretched lid fissure reaches less than 33mm after closing the defect after eyelid mass removal.

- The resultant defect is closed in two layers (a tarsal plate suture and a figure of eight suture) with absorbable 6/0 suture material, as previously described.

- A full-thickness incision at the lateral canthus, in the direction of the eyelid that is being lengthened, is performed.

- A triangle of skin (a relaxation triangle) is excised at the lateral end of the skin (the direction of the triangle is reversed to the location of the eyelid mass), which allows the skin to be slid medially.

- The resultant defect is closed in two layers with absorbable 6/0 suture material.

- No scar formation will occur within the new lid margin at the tumour removal site, and trichiasis will be restricted to the lateral margin (Figure 16).

- Sliding skin – outer lid margin flap (Landolt; Figure 17):

- A one-step procedure, indicated for larger upper and lower eyelid tumours.

- A full or partial excision of the mass with appropriate margins is performed.

- After lid splitting, a large flap of 10mm to 15mm in depth is dissected, followed by excision of a relaxation triangle at the end of the wound (the direction of the triangle is reversed to the location of the eyelid mass), which allows the skin to be slid medially.

- The sliding skin-outer lid margin flap is closed in one layer by a simple, interrupted suture (6/0 non-absorbable/absorbable suture material).

- The lid margin will undergo scar formation.

- H-figure sliding graft (H-plasty; Figures 18a to 18c):

- A one-step procedure, indicated for larger upper and lower eyelid neoplasm more than half of the eyelid margin.

- A full or partial thickness excision of the mass with appropriate margins is performed.

- An adjacent partial thickness advancement flap is created. For a full thickness defect, adjacent conjunctiva is advanced first into the defect and sutured with non-absorbable 6/0 (continuous pattern with buried suture).

- Two vertical slightly divergent skin incisions are continued at the base of the wound and they should be 1.5 to 2 times the length of the defect’s height.

- Two equal-sized relaxation triangles of skins are excised at the base of both skin excisions to enable shifting of the graft into the surgical wound.

- The skin flap is undermined and advanced into the defect; the leading edge of the skin graft should be slightly beyond (0.5mm to 1mm) the adjacent eyelid margin.

- The resultant defect is closed in two layers. The deeper tarsoconjunctival layer can be apposed by simple, continuous or interrupted absorbable sutures with the knots buried. The remaining muscle-skin lid is apposed with a simple, interrupted suture starting at the angled area (6/0 non‑absorbable/absorbable suture material).

- The potential disadvantages are trichiasis and a scarred new eyelid margin. Since the lower eyelid is less mobile, the incidence of trichiasis and keratitis after this procedure is lower.

Advanced blepharoplasties

For even larger eyelid margin excisions, other advanced blepharoplasties are indicated. These include a Z-plasty procedure (Figures 19a to 19c), mucocutaneous subdermal plexus (lip to lid; Figures 20a to 20d), Mustardé technique or Roberts and Bistner technique (Figures 21a and 21b; Roberts and Bistner, 1968; Munger and Gourley, 1981; Pavletic et al, 1982; Esson, 2001; Hagard, 2005; Hunt, 2006; Whittaker et al, 2010; Stades and Van der Woerdt, 2013). All of them apart from the Mustardé technique are one‑step techniques.

The resultant defect is closed in one/two layers. The deeper tarsoconjunctival layer can be apposed by simple, continuous, absorbable sutures with the knots buried. The remaining muscle/skin lid is apposed with a simple, interrupted suture (6/0 non-absorbable/absorbable suture material).

The posterior aspects of the H–figure sliding graft, Z-plasty procedures may be overgrown by conjunctival cells spontaneously or can be lined, for instance, by adjacent mucosa.

The first step of the Mustardé technique involves sharp dissection of the neoplasm of the recipient region of the upper eyelid followed by construction of a full‑thickness donor graft of the lower eyelid. The graft is then transposed to the upper eyelid defect and sutured in place.

The second step includes sectioning of the connection of the graft to the lower eyelid two weeks after the first procedure.

Closure of the lower eyelid defect can be achieved with various techniques – for instance, an advancement sliding skin graft (H plasty) or lip to lid.

The Mustardé technique should preferably be performed by an experienced ophthalmologist as complications are common.

Invasive neoplasms may require enucleation or orbital exenteration. If after enucleation the defect cannot be closed in a primary fashion then a caudal auricular axial pattern or an axial pattern flap can be performed (Stiles et al, 2003; Jacobi et al, 2008).

All of these advanced blepharoplasties are complex and referral to an ophthalmic surgeon should be considered.

Indications, pros and cons for eyelid procedures are detailed in Table 1.

| Table 1. Eyelid techniques: indication, pros and cons | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Eyelid procedure | Indication | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| V/four-sided wedge excision | Both eyelids, tumour smaller than 25 per cent | One-step procedure, primary closure of an eyelid defect | N/A |

| House inverted-triangle | Both eyelids | One-step procedure No scarred new lid margin at the tumour removal site |

Trichiasis of the lateral eyelid margin |

| Sliding skin – outer lid margin flap | Both eyelids | One-step procedure | Scarred new lid margin at the tumour removal site |

| H-figure sliding graft | Both eyelids | One-step procedure | Trichiasis (commonly occur on the upper eyelid) Scarred new lid margin at the tumour removal site |

| Z-plasty | Both eyelids | One-step procedure | Trichiasis Scarred new lid margin at the tumour removal site |

| Lip to lid | Lower eyelid, lateral canthus/lateral upper eyelid | One-step procedure Maintaining smooth new eyelid-like margins |

Trichiasis Wound dehiscence |

| Mustardé technique | Upper lid | Maintaining smooth eyelid margins The resulting eyelid margins are functionally and anatomically normal |

Two-step procedure During the first stage, the visual axis is partially obscured Micropalpebral fissure Trichiasis Wound dehiscence |

| Roberts and Bistner technique | Both eyelids | One-step procedure | Trichiasis |

- Figures 13a and 13b, 14a and 14b, 17a and 17b, 18a to 18c, 19a to c and 21a and b are modified drawings from Stades and Van der Woerdt (2013).