25 Jul 2023

Feline endocrinology: update on some key conditions

Laura Bree DipECVIM, DVMS, MVB, MRCVS covers hyperthyroidism, hyperaldosteronism and more in this insightful ‘refresher’ article for vets

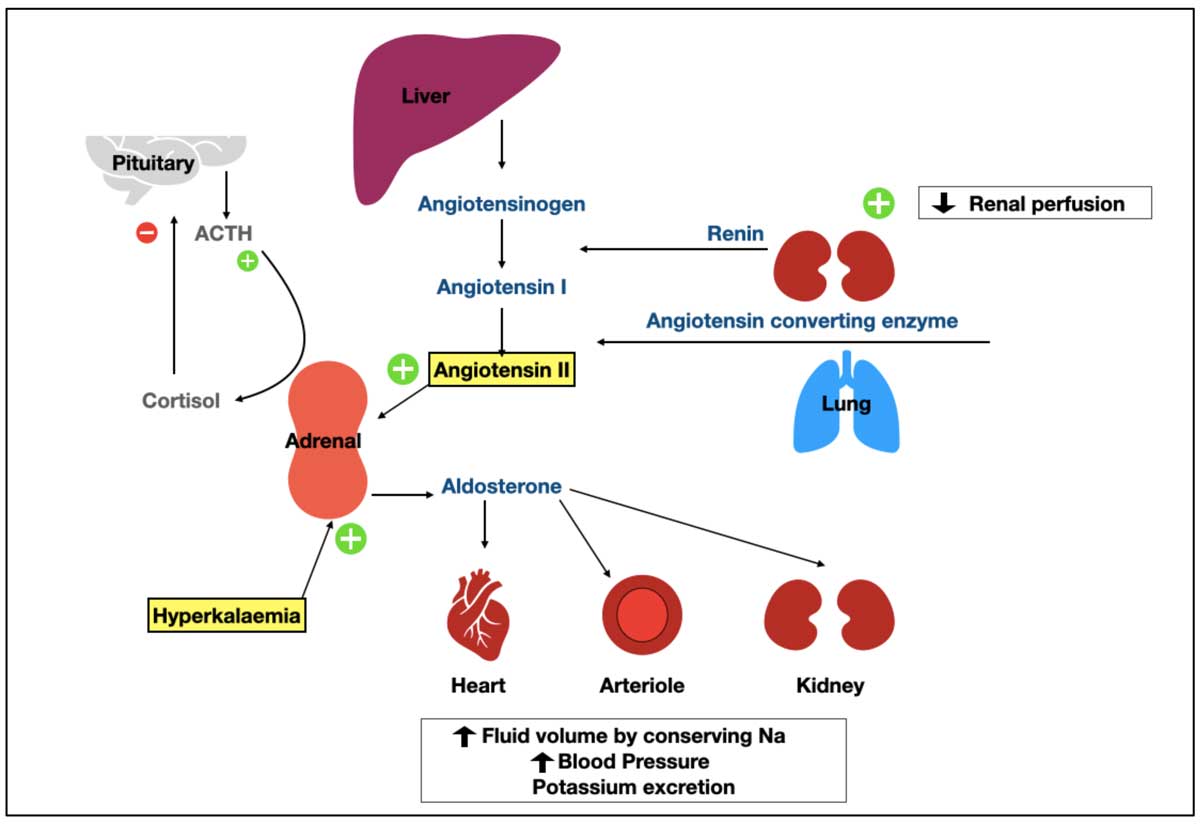

Figure 1. The renin-angiotension-aldosterone system (RAAS) and the pituitary adrenal axis. Decreased renal perfusion, caused by hypovolaemia or haemorrhage, stimulates release of renin from the kidney. Renin, with angiotensin-converting enzyme, activates angiotensin II, a powerful stimulator of aldosterone release from the adrenal gland. The other stimulus for aldosterone release is hyperkalaemia. Aldosterone acts on the kidney to promote sodium reabsorption, water resorption, and potassium excretion, resulting in increased blood volume, increased blood pressure and reduction in potassium. The regulation of aldosterone by extracellular fluid potassium concentrations is completely independent of the RAAS system. Hypokalaemia inhibits the secretion of aldosterone. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland have primary roles in stimulation of release of cortisol from the adrenal gland, but have little to no impact on aldosterone synthesis or secretion, aside from times of stress. Aldosterone is also minimally regulated by natriuretic peptides and a variety of neurotransmitters.

Feline endocrine disease is an interesting niche of internal medicine, with some conditions regularly seen in practice and others extremely rare. For example, we all have experience treating feline diabetes mellitus and hyperthyroidism, but many veterinarians will never see, or rather recognise, feline hyperaldosteronism.

The goal of this article is to refresh our knowledge on feline hyperthyroidism, but also to help ourselves recognise the more uncommon condition (or is it?), feline hyperaldosteronism.

Feline hyperthyroidism – a rapid refresh

Hyperthyroidism is recognised as the most common endocrinopathy in cats.Depending on the country, the prevalence of hyperthyroid cats presenting to primary care practice ranges from 7% (South Africa, in 2006) up to 20% (Poland, in 2014)1. Feline hyperthyroidism results from excess production of thyroid hormones (triiodothyronine and thyroxine; T3 and T4) from the thyroid gland.

In cats, hyperthyroidism is due to adenomatous hyperplasia of the thyroid gland, and, unlike for humans, is a disease independent of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Many theories exist to the cause of this adenomatous change in the gland in cats, including immunological, infectious, nutritional, environmental and genetic influence, but a single dominant factor, other than advanced age, has not been recognised2.

Research into a causative factor has produced weak associations with canned food, exposure to flea products, being indoors, and living in the city. These associations remain affected by many forms of bias and a lack of specificity (many factors being identified common to all cats).

A small proportion of cases have a functional thyroid carcinoma; the reported frequency of carcinoma is less than 2% of cases.

In cats, hyperthyroidism produces a range of clinical signs, and has a chronically aggressive effect on cats, with all requiring therapy. Clinical signs are reflective of the effect of thyroid hormone on cell metabolism (including carbohydrate and lipid metabolism), cardiorespiratory systems (including blood pressure, heart rate and response to hypoxia and hypercapnia), as well as bone metabolism and central nervous system health.

Four therapeutic choices in hyperthyroid cats exist: radioactive iodine therapy (RAI), surgical removal of the affected gland (thyroidectomy), iodine restricted food and anti-thyroid medication. The former two are defined as definitive therapy, resulting in “cure”, while the latter are regarded as “palliative”, or forms of managing the disease, without cure.

We, as veterinarians, are tasked with providing therapy options to owners, and managing the disease either short-term or long-term, depending on therapy choice.

Updates on hyperthyroidism

RAI: treatment of choice

RAI is still the treatment of choice due to high success and the presence of bilateral disease. It is considered the gold standard therapy in cats, as it is non-invasive and targets all thyroid-secreting tissue in the body, eliminating the risk of removing only part of the source of thyroid excess, as can occur with unilateral thyroidectomy.

A single treatment of iodine-131 (I-131) results in cure for more than 90% of cats, with survival times of two to five years post-therapy, and longer survival time compared to cats undergoing medical management.

However, RAI therapy can be more expensive than surgery, and requires isolation of the cat between five and 21 days depending on the facility, and the owner’s circumstances. Furthermore, since the COVID-19 pandemic, supply of injectable iodine has been unstable.

The main reason for declining cats for RAI therapy in this author’s experience is client preference (unwilling or uncomfortable with separation from their cat for a prolonged period of time), cats with concurrent diabetes mellitus, and cats with uncontrolled congestive heart failure.

Thyroidectomy is usually unilateral in the initial approach, and while it can provide a cure in cats with unilateral hyperplasia, and accurate removal of the affected gland, surgical complications such as parathyroid damage, damage to local nerves and so forth, as well as anaesthesia risk in geriatric felines, is an important consideration.

When considering these two options for definitive therapy, we must consider the distribution of the disease (unilateral or bilateral), as well as the presence of concurrent cardiac disease and risk of anaesthesia.

Overwhelming evidence describes the presence of bilateral disease in cats with hyperthyroidism at the time of diagnosis. This is set against evidence for the varying ability of veterinarians to identify goitre in cats with hyperthyroidism.

In one study, where 2,096 hyperthyroid cats underwent thyroid scintigraphy, 60% of cases demonstrated bilateral disease3.

In another study, examining prevalence of hyperthyroidism in Dublin, Ireland, a significant lack of accurate detection of goitre (any) in 102 hyperthyroid cats was recorded; only 39.2% (40) were reported as having detectable goitre1.

Of note, no significant difference was reported in thyroid hormone concentration between hyperthyroid cats with palpable goitre, and those that did not.

An interesting and positive finding in this cohort of cats was the detection of bilateral goitre (47.5%) in cats with palpable goitre, meaning where it was possible to palpate goitre, most veterinarians were accurate in detecting those with bilateral disease.

The failure of goitre recognition in more than half of hyperthyroid cats in this study was proposed to be due to a perceived low prevalence of hyperthyroidism in Ireland prior to this study. Palpating a goitre can also be very difficult in some cats; indeed, veterinarians listed that they were “unsure” of goitre presence in 14% of the hyperthyroid cats.

The presence of bilateral disease, earlier recognition of cats with hyperthyroidism, client education and the increasing popularity of insurance cover for our feline pets, has reduced the popularity of thyroidectomy, and increased the demand for RAI.

Indeed, many cats that underwent unilateral thyroidectomy will be referred for RAI therapy immediately postoperatively due to persistent hyperthyroidism, or in the one to five years post-surgery, for recurrence of the disease.

Ultimately, we as veterinarians must provide accurate advice about all therapy options to owners. This may require additional investigations, such as echocardiogram and ancillary blood and urine testing, to assess the overall health of the cat, and the stage of its hyperthyroidism.

What about iatrogenic hypothyroidism?

The prevalence of hypothyroidism post-RAI varies from 9% to 40%, depending on available evidence and the definition of hypothyroidism post-RAI therapy is in some part responsible for the variation, as well as the wide range of algorithms for the dosage of I-131 in hyperthyroid cats4-5.

From the available information, the key to diagnosing hypothyroidism requires T4 monitoring at one, three and six months post-RAI therapy, performing cTSH concentrations where T4 is below reference, routine monitoring of renal parameters, and clinical examination with special attention to weight gain over time.

The use of TSH concentrations has been demonstrated to be a sensitive method of detection of iatrogenic hypothyroidism in cats. In a study examining TSH concentrations in 28 azotaemic and hypothyroid cats post-I-131, 14 cats with euthyroid kidney disease, 14 euthyroid cats without kidney disease post-I-131 and 166 normal cats, TSH concentrations were more than 1ng/ml in all hypothyroid cats (median 3.3ng/ml), compared to medians of 0.05ng/ml, 0.11ng/ml and 0.4 g/ml in other groups, respectively6.

TSH can be measured accurately using canine TSH assays7. The development of azotaemia is common in cats post-reversal of hyperthyroidism; however, reduced survival has been proven in cats that develop azotaemia and hypothyroidism, compared to non-azotaemic cats with hypothyroidism.

Interestingly, no difference was reported in survival between euthyroid cats post-therapy with or without kidney disease8.

Assessing chronic kidney disease (CKD)

No perfect method exists to assess CKD pre-curative therapy (RAI or surgery).

Within RAI, much research exists seeking the ideal dosing regime for I-131, as well as identifying predictors of concurrent/masked renal disease in cats undergoing therapy.

Predicting the presence of CKD in cats with concurrent uncontrolled hyperthyroidism is difficult to achieve without first reducing thyroid hormone concentrations to reference intervals. Despite much research over the past decade, no one biochemical or urinary parameter can be relied on for correctly identifying or staging kidney disease in a hyperthyroid cat. Survival studies imply no effect exists of developing azotaemia post-I-131 treatment on survival9; however, identifying a predictor of CKD would still be useful for cat and client preparation.

A study examining serum symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) concentrations in cats pre-treatment, as well as one, three and six months post-RAI therapy, noted that finding an increased (author’s emphasis) SDMA concentration in a hyperthyroid cat can help predict the development of CKD post-therapy; however, it was very poorly sensitive (failed to predict CKD in most of the hyperthyroid cats) and was within normal reference interval in 28 of 42 cats that developed CKD post-therapy10.

The author implements a simple protocol for unmasking and evaluating CKD in cats with newly diagnosed hyperthyroidism pre-treatment: cats with newly diagnosed hyperthyroidism begin anti-thyroid medication (methimazole, felimazole, thiamazole or carbimazole) for four weeks, with examination, biochemical and urinary testing at three weeks to unmask and stage CKD.

Cats with International Renal Interest Society stage two kidney disease, or less at this time, are deemed suitable for RAI therapy.

Medical therapy is continued, until it is withdrawn at least two weeks prior to RAI therapy.

The decision to accept stage two CKD cats is based on the knowledge most cats will exhibit a 20% to 40% increase in their renal parameters post-treatment for hyperthyroidism (regardless of treatment modality).

The presence of azotaemia post-reversal of hyperthyroidism should not affect the decision to treat cats for hyperthyroidism, unless they are in severely advanced stages of their kidney disease. In these cases, lower dosages of anti-thyroid medication, to achieve a balance of clinical benefit between management of hyperthyroidism and their underlying renal disease, can provide a short-term palliation of their diseases.

Delaying RAI therapy in patients receiving medical treatment can lead to higher burden of disease, higher dose requirements of I-131 and reduced response to it. We should aim to treat all newly diagnosed and suitable cats with RAI within six months of their diagnosis.

Cobalamin low, but does not require supplementation

Of note, and for the benefit of our clinical awareness, a recent publication has demonstrated a functional cobalamin deficiency in cats with hyperthyroidism, which correlates with the clinical catabolic state and is reversible with the return of the euthyroid state11.Therefore, identification of hypocobalaminaemia in cats with hyperthyroidism is not considered an indication for supplementation. Treatment of hyperthyroidism will return cobalamin concentrations to normal.

Cobalamin assessment is commonly performed in older cats with gastrointestinal signs, as a marker of small intestinal malabsorption. Identification of hypocobalaminaemia in cat with compatible gastrointestinal signs could falsely guide diagnostics and therapy in cats with undiagnosed hyperthyroidism.

Decision regarding therapy is not always uniform

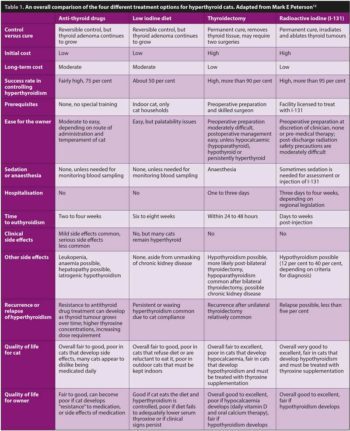

Mark Peterson, who has led extensive research in feline hyperthyroidism and I-131 therapy, provided a very interesting and useful recent review of the impact of treatment choice on the quality of life for cats and their owners (Table 1). Within this review, a comparison of the four treatment choices demonstrates the need for an individualised assessment of each cat and owner, to determinate the best therapy for their circumstances12.

Feline hyperaldosteronism – a rapid refresh

Hyperaldosteronism in cats is also called Conn’s disease, and is characterised by excessive secretion of aldosterone from the adrenal gland.

Aldosterone is produced by the zona glomerulosa and operates almost completely independent of adrenocorticotropic hormone action on the adrenal gland. It is instead activated by the presence of hyperkalaemia, or reducing blood volume, leading to the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and, conversely, inhibited by hypokalaemia and restored blood volume. The physiology and positive-negative regulation of aldosterone is described in Figure 1.

Aldosterone has two important physiological functions: it regulates extracellular fluid (ECF) volume, and is a major determinant of potassium homeostasis. Aldosterone regulates ECF volume in a variety of ways, namely via the nephron of the kidney, but also interacts with epithelial cells of the heart, kidneys, colon and salivary glands. Aldosterone plays a role in blood pressure regulation through its effect on blood volume, and the ECF, but also by increasing peripheral vascular resistance.

Primary hyperaldosteronism in cats was once considered a rare condition, but increasing evidence suggests this disease is a more common cause of arterial hypertension in humans and in cats, and its incidence may be underestimated. The pathogenesis in cats is due to a unilateral adrenal tumour, of either adenomatous or carcinomatous origin, or, bilateral hyperplasia of the adrenal glands, both of which leads to excessive autonomous secretion of aldosterone. Primary idiopathic hyperaldosteronism is sometimes used to describe the hyperplastic condition in cats. Secondary hyperaldosteronism refers to a chronic state of RAAS stimulation, as one sees in heart failure; in contrast, primary hyperaldosteronism causes renin suppression, and hyporeninaemia is expected13.

The distribution of unilateral tumours, and hyperplasia of both adrenal glands, is poorly understood in cats, as various studies have noted differing results. In humans, bilateral hyperplasia accounts for up to 60% of cases, with unilateral adrenal tumours noted in 30% to 35% of cases14.

In cats, literature would suggest a predominance of unilateral adrenal tumours, of which similar distributions of adenoma and carcinoma are present.

It is suspected that primary idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (hyperplasia of the adrenal glands) is underappreciated in cats, in comparison to the condition in humans, due to clinical underdiagnosis. The classic presentation in cats are middle-aged to older cats with signs of hypokalaemia (cervical ventroflexion, muscle weakness, can be periodic) and signs of arterial hypertension (mydriasis due to retinal detachment and blindness, CKD).

Concurrent diseases expected with hyperaldosteronism are due to the chronic effects of increased aldosterone secretion. Blindness and kidney disease are noted, but also weight gain from inactivity and, in some cases, congestive heart failure due to left ventricular hypertrophy from chronic hypertension.

Treatment of hyperaldosteronism ranges from medical management (spironolactone, potassium replacement, with or without anti-hypertensives, with or without cardiac medications) to surgical management (adrenalectomy), or both.

Updates on feline primary hyperaldosteronism

Interpreting equivocal aldosterone concentrations

Primary hyperaldosteronism should produce high aldosterone concentration, low renin concentration and hypokalaemia. Some difficulties exist in achieving and interpreting these results in cats for a few reasons.

It has been demonstrated that cats with unilateral adrenal tumours experience very high aldosterone concentrations, while cats with idiopathic hyperaldosteronism have only slightly increased aldosterone concentrations or within the upper limit of the reference interval.

Furthermore, a small proportion of cats will have potassium concentrations on the low end of the normal reference interval, and may not present with overt hypokalaemia. This cohort of cats may be more difficult to diagnose.

In cats with hypokalaemia, the presence of a mild increase or “high normal” aldosterone concentration should be considered inappropriate, and further investigations taken. Aldosterone measurement is easy to do and available widely in cats: the normal reference interval is 194pmol/L to 388pmol/L, where cats with adrenal tumours tend to be more than 1,000pmol/L15.

Concentration of aldosterone in cats with primary idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (adrenal hyperplasia), and cats with secondary hyperaldosteronism, can overlap.

What about plasma aldosterone to renin ratio?

Measurement of renin concentrations seems like a logical route to diagnosis in equivocal cases, where renin concentrations are expected to be low in cats with primary hyperaldosteronism, and high in cats with secondary disease (such as congestive heart failure).

In humans, a plasma aldosterone to renin ratio is considered a very useful aid in diagnosing primary hyperaldosteronism, and has been demonstrated in cats16. The accuracy of this ratio is dependent on the performance and sensitivity of the renin assay. Furthermore, renin should always be assessed alongside a control population (taking control samples from healthy cats at the time of sampling).

Measurement of renin requires blood collection in ice chilled tubes, plasma extracted via chilled centrifuge, and samples must be kept chilled until assayed. Failure to maintain chilled sampling and analysis leads to low renin concentrations, which could falsely diagnose a hyporeninaemic state.

In veterinary medicine, specialist endocrine laboratories are generally geographically quite distant from sites of sampling in primary care and referral practices, which could be limiting the use of sensitive assays such as renin assays.

The use of renin controls aids in reduction of this factor, but requires control cats and is costly.

What about urinary aldosterone to creatinine ratio (UACR)?

While aldosterone excretion appears to be mainly via bile and faeces in cats, in comparison to mostly urinary excretion in humans and dogs, UACR can be determined17. The urine can be collected at home, and a basal UACR can be performed without special handling. However, the reference range is very wide and has not been helpful in the reliable differentiation of healthy cats and those with primary hyperaldosteronism: in nine cats with primary hyperaldosteronism, only three had increased UACR. A normal UACR in cats is considered less than 46.5x10-9. A value of less than 7.5x10-9 seems to exclude primary hyperaldosteronism.

What about using fludrocortisone and UACR together?

One study examined the effect of fludrocortisone, a synthetic corticosteroid with mineralocorticoid activity, on aldosterone secretion, by measuring UACR in hypertensive cats with and without primary hyperaldosteronism18.

A dose of 0.05mg/kg by mouth every 12 hours for 96 hours was administered. Investigators noted significant suppression of aldosterone secretion (median 62% from baseline) in 19 hypertensive, but otherwise healthy cats, where varying (up to 70%) suppression occurred in only four of nine cats with hypertension due to hyperaldosteronism.

This study demonstrated that the diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism in hypertensive cats, with or without hypokalaemia, can be excluded if the UACR on day four suppresses more than 50% from baseline values.

However, this test requires twice-daily oral medication to cats, which are not always compliant for tableting; a daily urine test, which can be difficult to obtain at home from outdoor cats; and fludrocortisone can induce hypokalaemia and muscle weakness in both healthy and cats with hyperaldosteronism.

What about using fludrocortisone suppression testing and measuring plasma aldosterone?

Further research may prove promising in using fludrocortisone to plasma aldosterone, to diagnose primary hyperaldosteronism in cats19.

A pilot study has demonstrated that only three doses (36 hours) of fludrocortisone therapy in healthy cats significantly suppressed aldosterone concentrations. This study also demonstrated significant suppression of cortisol in cats receiving fludrocortisone. More research is required to evaluate the use and safety of a fludrocortisone-plasma aldosterone suppression test in cats for the diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism.

What about other adrenal hormones?

A recent study has identified the concurrent increase in progesterone concentrations in 10 cats with diabetes mellitus and primary hyperaldosteronism20. All 10 cats had a unilateral adrenal tumour. This highlights the importance of considering other adrenal hormone excesses in cats with hyperaldosteronism.

When should you perform imaging and what imaging is most useful?

Ultrasound is the most useful modality for examining adrenal size in cats. Most cats with primary hyperaldosteronism have a unilateral functional adrenal tumour (9mm to 30mm reported), causing contralateral reduction in adrenal size. Bilateral tumours are uncommon, but can occur. A low incidence of vascular invasion exists in the available literature, where it has been identified via CT. Cats with idiopathic primary hyperaldosteronism often have normal or increased adrenal measurements, but are not well described to date. The recognition of calcification of the adrenal gland should not be considered suspicious for neoplasia in cats, due to the presence of this finding in up to 33% of older cats.

Latest news