8 Mar

Gastrointestinal disorders in dogs

Ferran Valls Sanchez DVM, DipECVIM‑CA, MRCVS discusses key problems and diagnostic innovations, as well as the importance of a stable and healthy microbiome.

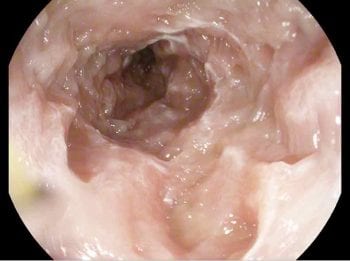

Figure 1. A gastroscopic image of a seven-year-old labradoodle with chronic vomiting. A large ulcer can be observed in the lesser curvature, along with a large amount of blood.

Chronic enteropathies are common in canine medicine. Making it very simple, the most important groups are the chronic inflammatory enteropathies (CIEs) and neoplastic disease.

Other important differential diagnoses for chronic gastrointestinal (GI) signs include infectious disease (for example, parasites), pancreatic disease (pancreatitis and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency [EPI]), congenital abnormalities in young animals (for example, pyloric hypertrophy) and GI ulceration (Figures 1 and 2).

Some of these conditions can cause a protein-losing enteropathy (PLE), which is a syndrome and not a disease per se. PLE is characterised by the loss of albumin through the GI tract and consequent clinical signs (for example, abdominal effusion, pleural effusion or peripheral oedemas).

In comparison with CIEs, neoplasia affecting the GI tract are less common. The most common gastric tumour is carcinoma (Figure 3). Other possible gastric tumours are smooth muscle tumours (leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas) and GI stromal tumours (GISTs). The most frequent intestinal tumour is lymphoma, followed by adenocarcinoma, and then leiomyosarcoma and GIST. The most common tumours in the large intestine are adenocarcinomas (Figure 4), lymphomas and GISTs.

CIEs are characterised by chronic signs (persistent or recurrent), and histological evidence of inflammation in the lamina propria of the small and/or large intestine. They can be subdivided into the following groups, depending on the response to treatment:

- food-responsive enteropathy (FRE)

- antibiotic-responsive enteropathy (ARE)

- immunosuppressant-responsive enteropathy (IRE) or non-responsive enteropathy – the term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is often used to describe this group

Diagnostic approach to chronic GI signs

Signalment, history and physical exam

Signalment helps ordering the differential diagnoses – for example, English bulldogs and boxers are affected by ulcerative colitis; puppies and young dogs are more likely to be affected by foreign bodies, infectious processes, congenital abnormalities and FRE; while in older animals IBD and neoplasia are more common.

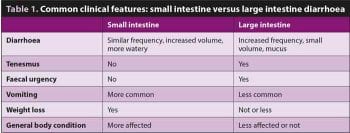

Clinical history will help, if you are more suspicious about GI or extra-GI issues. Being more suspicious about a small intestine or large intestine problem (Table 1) will help later in the course of the investigations, helping you decide whether an upper GI scope or colonoscopy (or both) may be more useful.

Finally, physical exam is fundamental for multiple reasons: to see if the patient is stable, to set a baseline of bodyweight/body condition score (which is a very useful parameter to monitor response in enteropathies) and again, giving clues about the underlying cause (for example, jaundice will point towards liver disease).

Faecal analysis

Parasitology is particularly indicated in puppies or animals with a recent history of kennelling. In adult dogs, a course of fenbendazole might be dispensed without performing parasitology as part of the first-line treatment for CIEs.

Zinc sulphate flotation (ideally three samples) is the technique of choice for detection of Giardia species, but an in-clinic Giardia SNAP is also available and has a similar sensitivity. Immunofluorescence antibody test is considered the gold standard. The combination of faecal flotation and SNAP test has been suggested to have the highest sensitivity (97.8%)1.

Blood tests

In chronic cases, the first step is to try to rule out extra-GI causes and biochemistry is essential to screen for any evidence of hepatic, pancreatic or renal disease, and to detect potential hypoalbuminaemia, which could suggest PLE (low albumin usually combined with low globulins and cholesterol).

Basal cortisol is helpful to rule out hypoadrenocorticism in dogs. If the serum/plasma concentration is above 55µmol/L, hypoadrenocorticism can be excluded2, but an adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test is recommended to confirm/exclude this endocrinopathy.

It is important to bear in mind that Addison’s disease can be present even if electrolytes (sodium, potassium and their ratio) are within normal limits (atypical Addison’s disease). Recent publications have studied the prevalence of Addison’s disease in cases with chronic GI signs, reporting from 1/298 cases with final diagnosis of Addison’s disease to 6/151 in dogs with chronic GI signs3,4.

Cobalamin is normally absorbed in the ileum; therefore, hypocobalaminaemia is suggestive of intestinal disease and requires supplementation. Oral supplementation is now available and proven to be an effective method of supplementation in dogs with chronic enteropathies5.

It is important to evaluate cobalamin along with trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) – especially in cases where EPI is part of the differential diagnosis because this condition can also cause hypocobalaminaemia (due to decreased production of intrinsic factor, which is produced mainly in the pancreas and is necessary for cobalamin absorption).

Folate is absorbed in the proximal small intestine and low folate suggests small intestine disease. The benefit of folate supplementation is unknown, but it is usually supplemented if it is very low. Increased folate has been associated with small intestine bacterial overgrowth, which can occur with different enteropathies.

TLI serum concentration lower than 2.5µg/L is suggestive of EPI if the clinical signs are compatible. A TLI value between 2.5µg/L and 5.7µg/L must be interpreted with caution, and repeated evaluation is indicated a few weeks later along with exclusion of other causes.

The diagnosis of clinical pancreatitis is challenging, and combining different tools (blood tests and ultrasound) and excluding other differential diagnoses is the most sensible approach. Increased canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI), 1,2-o-dilauryl-rac-glycero-3-glutaric acid-(6’-methylresorufin) ester (DGGR) lipase and in amylase/lipase (if three to five times) may be suggestive of pancreatitis.

Abdominal imaging

Abdominal ultrasound is a widely available non-invasive diagnostic tool and still part of the basic approach for many clinicians. It may help increase the suspicion of inflammatory enteropathy, congenital abnormality or neoplastic process, and it enables assessment of multiple organs (for example, pancreas, liver). Other advantages include the ability to perform ultrasound‑guided fine needle aspirates and, in cases where intestinal biopsies are warranted, to help decide whether a surgical or endoscopic approach is best.

Ultrasonographic changes suggestive of CIE include the presence of hyperechoic mucosal speckles and striations, and increased intestinal wall thickening. The intestinal wall layering is usually preserved. Abdominal effusion can also be present in cases of severe hypoalbuminaemia. Neoplastic processes (as compared to inflammatory diseases) generally cause more severe wall thickening and loss of layering, and can be either focal or diffuse, but a focal lesion is more supportive of neoplasia. If obstruction is present it is usually associated with a neoplastic process. Lymph nodes are usually larger with neoplasia.

Importantly, the absence of ultrasonographic changes does not exclude an enteropathy, including neoplastic enteropathy. For example, according to a study including cases of intestinal lymphoma, 5 out of 65 did not have any intestinal ultrasonographic abnormalities6. Obtaining biopsies is, therefore, the main benefit of performing endoscopy.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy allows the assessment of the upper and lower GI tract (colonoscopy) for detection of many types of lesions – such as wall granularity, lacteal dilation, mass lesions and ulceration – and to take biopsies for histopathology (Figure 5). Preparation of the patient prior to endoscopy is fundamental for a good visualisation of the GI wall: starvation for 24 to 48 hours, and administration of oral laxatives and enemas (the latter for colonoscopy).

Gastric lesions may not be isolated, and the duodenum should be evaluated if achievable, regardless of the presence or absence of gastric abnormalities. The main advantage of endoscopy is that it allows sampling. Biopsies of different parts of the stomach (pylorus, lesser curvature, fundus, cardias), duodenum and colon (ileum, ascending, transverse and descending) should always be taken, even if no macroscopic abnormalities are detected, as visual appearance does not correlate well with histopathological findings.

At least eight to 10 biopsies from each anatomical area (stomach, duodenum, colon) should be taken. Equally, it is important to wait for the histopathology results of any mass lesion before making a conclusion (Figures 6 and 7).

Some disadvantages of endoscopy are the size of the biopsies, superficial character and variable quality of them. Besides, general anaesthesia is required.

Indication for performing both upper and lower GI endoscopic examinations is based on the signalment of the patient, type of diarrhoea, other clinical signs and response to previous treatments.

A study concluded that animals with both small and large intestinal diarrhoea should have biopsies taken from both approaches (duodenum and ileum) given the possibility to miss the diagnosis in a relatively large number of cases and high level of diagnostic disagreement between these locations7. However, further studies are needed to determine to what degree performing none, one or both procedures affect the treatment decisions.

Exploratory laparotomy

Surgical biopsies are indicated when changes in deeper layers of the GI wall occur, when the lesion(s) is (are) not reachable endoscopically, or when abnormalities outside of the GI exist. Other factors to consider when deciding between a surgical or endoscopic approach are the albumin level (risk of dehiscence), anaesthetic risk, and time and cost. A recent study about the risk factors for dehiscence did not conclude hypoalbuminemia8; however, the numbers of cases of dehiscence was low and the severity of the hypoalbuminaemia in the included cases was not described. Unless fundamental (surgery may be curative or no other sampling is feasible), in patients with hypoalbuminaemia it is the author’s opinion to perform endoscopy in favour of surgical biopsies.

Histopathology (endoscopic or surgical biopsies)

It is essential to note that GI histopathological results should be interpreted along with the rest of the investigation findings, and bearing in mind the effects of the potential contemporary treatment(s) and therapeutic trials the patient has undergone. For example, FRE and IBD may have the same histopathological conclusions, but their management is very different.

Lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is the most common inflammatory type in IBD1. The correlation between histological results and clinical activity was considered poor; however, a recent study using a more simplified scoring system showed a good correlation9.

Granulomatous colitis is a particular type of inflammatory process affecting the large intestine in which Escherichia coli plays an important role, and has been reported most commonly in boxers, French bulldogs and English bulldogs. Periodic acid-Schiff stain or fluorescence in situ hybridisation can be performed in colonic biopsies to confirm the diagnosis.

Further tests, such as immunohistochemistry or PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement, can be performed on the biopsies when lymphoma is suspected.

This list of diagnostic tools is not exhaustive and should be adapted on an individual basis, taking into consideration the signalment of the patient, clinical signs, availability of the tests, response to treatment and financial constraints.

CIEs

Although the exact cause for CIEs is not well understood, it is accepted the pathogenesis involves host genetics, intestinal mucosal immune system, diet and intestinal microbiota. The simplified, current hypothesis is that an overly aggressive immune response exists due to loss of tolerance to normal microbiota and food, in a genetically predisposed individual.

Breed predispositions have also been found in dogs and a specific mutation was found to be associated with IBD in a population of multiple breeds. However, it is suspected that defects in multiple genes are needed for the disease to appear. Microbiota changes are found in animals with chronic enteropathies, and some enteropathies solely respond to antibiotics, supporting an important role of the microbiota on the pathogenesis of these conditions (see later).

FRE

A marked response to diet management alone in more than 50% of cases of chronic enteropathy has been shown in multiple studies10 – this is the reason why a diet trial is usually the first diagnostic and therapeutic tool (if the dog is stable and has good appetite).

Usually, patients with FRE are younger, large-breed dogs with colitis signs. No evidence exists of a benefit of using a hydrolysed diet (proteins are broken down into peptides to reduce antigenic reaction) over a novel antigen diet (novel protein and carbohydrate source) – good outcomes have been achieved with both10. Clinically, most dogs respond quickly, but some may take up to 14 days2. Some animals can be switched back to the previous diet after 12 weeks, but it is easier sometimes just to keep the patient on the hypoallergenic diet if possible.

A low-fat content is recommended if a query about concomitant pancreatitis or lymphangiectasia exists. Some cases of large intestine diarrhoea respond to a high-fibre diet.

ARE

ARE is rare, with recent studies suggesting a prevalence between 8% and 16% in dogs with chronic diarrhoea11. Consequently, antibiotics are not usually indicated for most of the cases. Besides, antibiotics can cause severe gut dysbiosis and can contribute to increased antibiotic resistance, which is an important small animal – but also human – concern. German shepherd dogs are predisposed to it.

According to a recent proposal, the use of antibiotics should be reserved for cases where non-infectious causes have been excluded and other trials have failed, and only mild changes are found histopathologically11. Treatment is usually recommended for four to six weeks, but no published evidence exists to determine the optimal duration.

Antibiotics that are commonly used are metronidazole, oxytetracycline or tylosin. Antibiotics may also be used when systemic inflammatory response syndrome is suspected (pyrexia, neutrophilia).

An exception, where antibiotic therapy is considered first line treatment, is granulomatous/ulcerative colitis in boxers and French bulldogs, in which an association between presence of bacteria and clinical signs has been very well described (enrofloxacin is usually chosen, but culture of the colonic mucosa is advised).

IRE

If a primary enteropathy is suspected, and the dog has not responded to a diet trial and worming, usually the animal is considered to suffer from IRE (unless it is a breed predisposed to ARE); however, this may be confirmed retrospectively once the dog has received an immunosuppressant.

Prednisolone is commonly used as a first line immunosuppressant. Depending on the severity, prednisolone (1mg/kg to 2mg/kg by mouth once a day) can be used alongside a diet trial, which is often done if PLE exists. Depending on the response, the treatment is stepped down in responders or stepped up (change dosage or drugs) in non-responders.

Some other drugs that are used in CIE are budesonide (as an alternative to prednisolone) or azathioprine, chlorambucil or ciclosporin as second line immunosuppressants or rescue agents. Another study did not conclude any benefit of adding metronidazole to prednisolone10. Ciclosporin was suggested to be a good rescue agent in steroid refractory cases in a study with a small number of cases12. Sulfasalazine is used in dogs when IBD is limited to the large intestine.

No evidence exists of when to use a combination of immunosuppressants, but this approach should be considered in patients expected to develop more steroid side effects (large breeds) and when the disease is very severe. For example, clinical indices are available, such as the canine chronic enteropathy clinical activity index (CCECAI) – if this is above 12, the prognosis is considered much poorer12; in these cases, it may be useful to start with a more aggressive approach. Chlorambucil or ciclosporin would be the second line choices, in the author’s opinion.

A study with a dog with PLE concluded the combination of prednisolone plus chlorambucil to be superior to prednisolone plus azathioprine1. In cases of PLE, tests to assess for evidence of hypercoagulability (for example, thromboelastography) are recommended to decide if therapy to prevent thromboembolism is started (ultra-low dose aspirin or clopidogrel) or not (Figure 8).

Finally, a concern exists about the long-term success of all these treatments as some studies do not show a very good success rate after long periods of time, with relapse of the clinical signs.

A study of 80 cases with IBD reported 21/80 cases go into remission, 40/80 continued to have intermittent signs, 3/80 had uncontrolled signs and 10/80 were euthanised due to refractory signs13. In another study including CIE, 13/70 had intractable disease14. These numbers emphasise the idea that CIE can be very severe and it is important to transmit this idea to the owner, who often feels relieved once “cancer” is not diagnosed, to avoid false expectations. Prognosis is better for FRE than ARE and steroid-responsive enteropathy14.

Negative prognostic factors for dogs with chronic enteropathies (some studies only included IBD cases, others were a more general population) are higher CCECAI, higher endoscopic score, hypoalbuminaemia, hypocobalaminaemia and increased cPLI. Some studies also suggested increased C-reactive protein13,15. Low vitamin D has been associated with a poorer outcome in dogs with chronic enteropathy16. Higher expression of P-glycoprotein in intestinal biopsies was associated with a worse response (however, this test is not commercially available)12.

GI microbiota: disease and therapeutic implications

Currently, the study of intestinal microbiota is a very active area of research; however, it is very “young”, and many more studies and knowledge are necessary.

The intestinal microbiota is the collection of all live microorganisms that inhabit the GI tract. Interaction occurs between this microbiota and the host immune system. Many human and animal studies have associated intestinal dysbiosis (alteration in intestinal microbiota composition, richness and its metabolites’ production) with various disorders. For this reason, normalisation of the dysbiosis appears to be a prudent therapeutic goal.

The predominant phyla in the faeces of healthy dogs are Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria and Proteobacteria17. These groups are part of the intestinal barrier and protect from pathogens, but also produce metabolites that have a direct impact on host health – for example, they produce:

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which act as an energy source, regulate intestinal motility, are important growth factors for epithelial cells and are anti-inflammatory molecules.

- Indoles, which have anti-inflammatory actions.

- Secondary bile acids, which also have anti-inflammatory actions.

Several physiological mechanisms regulate microbial colonisation in the GI tract, including gastric acid, bile, pancreatic enzymes and motility, among others. Rapid diet changes, dietary indiscretions and changes in the architecture of the intestine (for example, surgical resection) are also associated with dysbiosis.

IBD also causes microbiota changes with a shift towards Gram-negative bacteria (for example, Proteobacteria) which may perpetuate disease17. Equally, in dogs with IBD, decrease of some major bacterial groups exists, such as Lachnospiraceae or Ruminococcaceae – these are normal and protective microbiota, and usually produce SCFAs and other immunomodulatory metabolites17.

The best therapeutic approach for dysbiosis is unknown; use of probiotics or faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) are possible options.

Probiotics

The greatest amount of data is available for amelioration and/or shortening of dogs with acute diarrhoea. In dogs suffering from acute idiopathic diarrhoea, it took fewer days for the signs to resolve and in dogs with parvovirus the mortality decreased17.

Another area of interest is the use of probiotic in a prophylactic way for antibiotic-induced dysbiosis. However, a systematic review from 2018 about the clinical effect of probiotics in prevention and treatment of GI diseases in dogs pointed towards a very limited – and possibly clinically unimportant – effect for prevention and treatment18. Importantly, the same review pointed out that larger, randomised controlled studies are needed to achieve better evidence for or against use of probiotics.

A recent study concluded the use of Saccharomyces boulardii in dogs with chronic enteropathy could help in achieving a better clinical control (clinical indices, stool frequency and consistency, and body condition score)19. Another study with dogs with canine fibre-responsive diarrhoea responded well (resolution of signs) to a combination of a high-fibre diet and a probiotic mixture20.

Regarding probiotics’ side effects, they have the potential to cause systemic infections and it is currently recommended to use them with caution in immunocompromised individuals17. In humans, a limited number of case reports have associated probiotics with sepsis, endocarditis and in cases of severe pancreatitis an increased mortality was found with probiotic therapy17,21.

FMT

FMT is another treatment to try to control dysbiosis. This consists of administration of faecal matter from a healthy donor to a patient (endoscopically or orally). In human medicine, this treatment is successful for the treatment of Clostridium difficile and its use has been reviewed for many other human pathologies. Regarding human IBD, the success rate varies between 22% and 60.5%22.

In veterinary medicine, minimal information is currently available about FMT. In a study including puppies with parvovirus, a significant reduction in hospitalisation time and a faster recovery was found20. Regarding chronic enteropathies, a small study with 16 cases of IBD receiving FMT (cases refractory to standard therapy) showed a clinical improvement in most of the patients22.

Another recent case report described successful long-term results of FMT in a dog with IBD, which had not responded to multiple treatments23. Therefore, this treatment could be considered a resource despite the current absence of strong evidence – especially in non-responsive cases. As in the case of probiotics, further studies are needed to find the ideal protocol (route of administration, frequency) and evaluate its utility.

In conclusion, the knowledge about gut microbiota and its therapeutic implications is limited, and further research is needed, as from a theory point of view it is a promising area to discover new tools and improve the management of GI disease.

- Some drugs mentioned in this article are used under the cascade.

Latest news