9 Apr 2018

Leg mass in a dog

Francesco Cian looks at the case of an eight-year-old mixed-breed dog with a large mass on its leg in the latest from Cytology Corner.

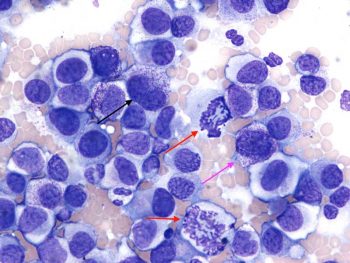

High magnification photomicrograph of the fine needle aspirate from the mass (Wright-Giemsa, 50×).

This macroscopic image (right) shows a large mass on the leg of an eight-year-old, mixed-breed dog.

A monomorphic population of discrete, round cells are individually distributed throughout the smear. These cells have moderate amounts of lightly basophilic cytoplasm, with distinct borders – often containing small numbers of fine, purple/magenta granules (pink arrow) – occasionally obscuring the nuclei.

When visible, nuclei appear round to slightly oval, paracentrally located, with coarse granular chromatin and small, round nucleoli occasionally seen.

Anisocytosis (cell size variation) and anisokaryosis (nuclei size variation) are moderate, and binucleated cells (black arrow) and frequent mitotic figures (red arrows) exist. Occasional neutrophils, likely blood derived, are also noted.

Interpretation: mast cell tumour

Mast cell tumours represent the most common cutaneous tumour in dogs, accounting for between 16% and 21% of all cutaneous neoplasms (Blackwood et al, 2012). They can occur in dogs of any breed and age; however, certain breeds are at increased risk – including boxers, Labrador retrievers, golden retrievers and cocker spaniels.

Most mast cell tumours in dogs occur in the dermis and SC tissue, and most are solitary in nature. Common locations include the trunk, perineal region, limbs, head and neck.

It is important to note mast cell tumours have an extremely varied range of clinical appearance, and can be easily mistaken for other neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions – for example, lipoma – based on macroscopic appearance only. This is one reason why fine needle aspiration of cutaneous and SC lesions is always strongly recommended.

The clinical behaviour of mast cell tumours can vary widely and is best predicted by evaluating prognostic factors, such as histological grade, clinical stage of disease, anatomic location and proliferative markers (for example, Ki67 nuclear protein and the c-KIT gene).

A few cytological grading systems for canine cutaneous mast cell tumours have been proposed. Scarpa et al (2016) evaluated the applicability on fine needle aspirations of the novel Kiupel grading system, based on the numbers of mitoses, multinucleated cells and bizarre nuclei, and presence of karyomegaly.

Meanwhile, Camus et al (2016) proposed a two-tier cytological grading scheme based on morphological characteristics of neoplastic cells. A mast cell tumour is classified as high grade if it is poorly granulated or has at least two of the following findings:

- mitotic figures

- binucleated or multinucleated cells

- nuclear pleomorphism

- more than 50% anisokaryosis

According to Camus et al (2016), the cytological grading scheme had 88% sensitivity and 94% specificity relative to histological grading. Dogs with histological and cytological high grade forms were 39 times and 25 times more likely to die within the two-year follow-up period, respectively, than dogs with low grade mast cell tumours.

Latest news