5 Feb 2018

Lungworm in dogs: signs, latest insight and treatment protocols

Hany Elsheikha looks at data on the clinical signs, diagnosis and management of canine angiostrongylosis in the UK.

We are away from the days when canine angiostrongylosis was first discovered in the British Isles – 1968 in a greyhound in Ireland. However, the causative agent, Angiostrongylus vasorum, is still a leading cause of morbidity and mortality by a single parasitic disease in small animal practice. The fatal outcome is high in the absence of adequate and timely treatment, despite the parasite being susceptible to many anthelmintics. Moreover, the geographic range of this parasite has been expanded due to many factors. These findings, together with the increasing numbers of confirmed cases of canine angiostrongylosis, have thrown A vasorum into the spotlight nationally and globally, driving research into its epidemiology, diagnosis and risk factors.

Canine angiostrongylosis is a parasitic disease with a myriad of possible presentations and, therefore, presents a diagnostic challenge for vets. The most common presenting signs relate to the cardiorespiratory system and include dyspnoea, pulmonary hypertension and coughing. Other clinical signs include disorders of haemostasis (with associated haemorrhage) and neurological signs. Therefore, proper understanding of the pathophysiology of these disorders could guide the rational development of new treatment regimens that target key molecular mechanisms, reducing later relapse and adverse health consequences. Here, the author briefly summarises latest data on the clinical signs, diagnosis and management of canine angiostrongylosis.

The metastrongyloid nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum is the agent of canine angiostrongylosis and has emerged as a significant vector-borne respiratory pathogen in UK dogs during the past 20 to 30 years (Morgan and Shaw, 2010).

Dogs become infected after ingesting the third larval stage (L3), usually within an intermediate gastropod host or a paratenic host, such as a frog or chicken (Bolt et al, 1993; Mozzer and Lima, 2015). Infected snails of the species Biomphalaria glabrata and infected slugs of the species Limax maximus have been shown to shed L3 into the environment, creating a free-living reservoir of infection (Barçante et al, 2003; Conboy et al, 2017).

UK-based epidemiological surveys to determine the distribution and prevalence of angiostrongylosis have been conducted, and it is reported to be spreading throughout the UK from its original endemic foci in the south-west and Wales (Morgan et al, 2005; Morgan and Shaw, 2010; Kirk et al, 2014; Helm et al, 2015).

The UK and Ireland branch of the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites provides up-to-date practical advice to veterinary professionals and pet owners on protecting dogs from angiostrongylosis and other parasitic diseases. Also, an interactive UK lungworm distribution map (www.lungworm.co.uk/lungworm-map) can be used to check for reported cases of A vasorum infection in any locality of the UK.

Canine angiostrongylosis has also been reported throughout Europe, where it represents an emerging parasitic infestation (Guardone et al, 2013; Lurati et al, 2015).

These facts – together with the presence of undescribed potential vectors and reservoirs in new areas – the lack of knowledge of the parasite immunology and pathogenesis, and poor awareness, can lead to the risk of increasing the potential geographic expansion of this parasite, which could challenge treatment schemes, as well as the possible appearance of angiostrongylosis in localities where it is not yet endemic.

Clinical signs

During the past two decades, several studies have tried to define the characteristic clinical signs associated with this disease. A vasorum resides in the cardiovascular system and causes a variety of clinical signs ranging from mild respiratory disease to haemoptysis, dyspnoea, syncope, coagulopathies and neurological signs (Jefferies et al, 2009). Mortality rates can, however, be high in severe cases despite intensive treatment (Chapman et al, 2004; Koch and Willesen, 2009). Canine angiostrongylosis can cause substantial derangement of both primary and secondary haemostasis (Brennan et al, 2004). This derangement in clotting leads to many dogs being referred due to the serious complications that can develop (Koch and Willesen, 2009; Lowrie et al, 2012).

Ocular signs, including intraocular larval migration, while rare, have been reported (Manning, 2007; Colella et al, 2016). Even though this disease often presents with variable clinical signs, in some cases the infection may be entirely subclinical. In fact, a major concern with canine angiostrongylosis is it may remain largely subclinical and, in some cases, manifests as sudden death (Brennan et al, 2004). The lack of a clear pathognomonic profile and the ambiguity of clinical signs may delay anthelmintic treatment while another suspected cause is investigated, resulting in more severe pathology.

Diagnostics

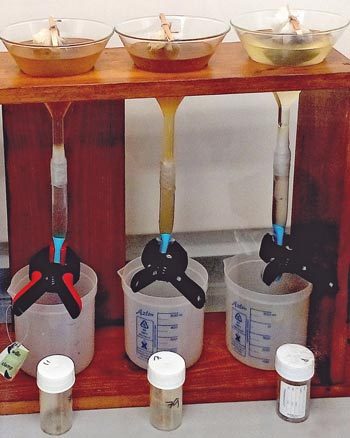

Traditional methods used to diagnose lungworm infections have been based on microscopical examination of faecal samples. Because A vasorum female worms deposit larvae (Figure 1) instead of eggs, Baermann is the method of choice (Figure 2). Ideally, this technique requires faecal samples to be collected from the same animal on three successive days and the results can be influenced by the intermittent shedding of larvae. However, the Baermann method is commonly used and has an acceptable level of sensitivity (Elsheikha et al, 2014).

A number of molecular diagnostic methods are available and can be used to confirm a suspected case of canine angiostrongylosis. The Angio Detect test, for example, is gaining more popularity – perhaps because of its simplicity and rapidity of obtaining results in almost 15 minutes. The test offers an attractive screening tool to vets due to its convenience, as well as being relatively inexpensive.

Despite its specificity of 100%, its sensitivity of 84.6% is lower than that of the external ELISA (94.9%) and, therefore, Angio Detect is less suited as a screening tool (Schnyder et al, 2014). The possibility of receiving a falsely negative result via Angio Detect makes it advisable for vets to adopt an alternative testing modality to confirm this result, if the case carries a high suspicion of angiostrongylosis.

MRI is the modality of choice when assessing neurological damage, with the possible consideration of CSF analysis; however, this is contraindicated in patients suffering from increased intracranial pressure due to the risk of brain herniation that may follow the acquisition of the CSF (Wessmann et al, 2006). Diagnosis of the ocular infestation by A vasorum larvae can be achieved by direct visualisation using a pen torch. Also, larvae can be aspirated via anterior chamber paracentesis (ACP) for morphological characterisation to determine the species (Manning, 2007).

However, ACP is likely to take place at a referral practice due to the highly specialised nature of the procedure. In this case, faecal examination may be a cheaper alternative for the pet owner. It is important to mention a negative faecal examination was obtained in a dog that already had A vasorum within its eye (Colella et al, 2016). In a referral setting, treatment of the underlying A vasorum infection, together with the removal of worms present within the eye via ACP, can provide an effective treatment approach (Colella et al, 2016).

Considering the importance of A vasorum as a cause of serious health complications, the combined use of a parasite microscopic detection method and antibody or antigen assay concurrently may give more useful information than using a single method. In geographical regions with a high prevalence rate of A vasorum, therapy should be guided by such analysis.

Management of angiostrongylosis

In the UK, macrocyclic lactone-based products – containing moxidectin, normally in a topical form (along with imidacloprid) or milbemycin oxime, usually in tablet form – are licensed to treat angiostrongylosis. The experimental efficacies of these drugs have already been studied. The treatment efficacy for a single dose of the formulation of imidacloprid/moxidectin was found to be 85.2% (with no statistically significant difference from the 91.3% efficacy of 20 days of daily fenbendazole, which is unlicensed for the treatment of canine angiostrongylosis). Of those dogs still shedding larvae that received a further dose of imidacloprid/moxidectin, all were then found to be Baermann negative (Willesen et al, 2007).

As well as being licensed for the treatment of adult worms, imidacloprid/moxidectin is also licensed for monthly use in the prevention of angiostrongylosis and patent infection, with 100% efficacy against L4 larvae and immature adults (L5) of A vasorum (Schnyder et al, 2009).

In regards to milbemycin oxime, commonly available in combination with praziquantel, a two-dose protocol achieved a clinical improvement, but without clearance of larval shedding, and treatment was, therefore, extended to using four, weekly treatments to reduce the level of infection, achieving negative faecal Baermann results in 14 out of 16 dogs (Conboy, 2004).

Monthly use of milbemycin oxime is indicated for the prevention of angiostrongylosis by reduction in the level of infection by immature adult (L5) and adult parasite stages, with a study showing a worm count reduction efficacy of 94.9% (Lebon et al, 2016).

Although some case reports have indicated the efficacy of fenbendazole in treating angiostrongylosis (Brennan et al, 2004; Chapman et al, 2004; Manning, 2007), a clinical trial is needed before advice can be given as to the optimal dosage and frequency of administration. In the past, levamisole was advocated for the treatment of angiostrongylosis due to its potency and rapid onset of action. In recent years it has fallen out of favour as clinicians began reporting cases of anaphylaxis and even hypovolaemia in levamisole-treated patients, attributed to the sharp rise in circulating parasite antigen (Søland and Bolt, 1996).

Besides anthelmintic treatment of the underlying infection, the immunosuppressive activity of corticosteroids has been suggested in the control of respiratory damage to reduce inflammation and the fibrosis of lung tissue (Morgan and Shaw, 2010). The use of bronchodilators and provision of oxygen to patients in severe respiratory distress is advisable, but must be tailored to individual cases. In regards to coagulopathy associated with angiostrongylosis, dogs with acute haemorrhage, or at risk of developing hypovolaemic shock, should be given fresh, frozen plasma, or whole blood (preferably type-matched), to replace the missing clotting factors while the underlying infection is treated (Koch and Willesen, 2009).

Finally, it is important to emphasise prior to prescribing any antiparasitic therapy a full parasite risk assessment should be performed.

Conclusion

A vasorum has spread from its original southern hotspots and is now found throughout mainland UK, with cases reported as far north as Scotland. However, this parasite’s geographical range has expanded faster than our knowledge of its pathogenicity and epidemiology. Given infections caused by A vasorum have continued and expanded, serious consideration must be given to identifying potential underpinning reasons for parasite expansion.

Because effective treatment of A vasorum infection depends on a timely and correct diagnosis, it is important to use the best available diagnostic tools to detect it, to better guide treatment decisions. Considering the importance of A vasorum as a cause of potentially serious infections in dogs, it is recommended a combination of parasite microscopic detection and molecular diagnostic techniques for early detection be included in the standard practice for the investigation of lungworm-like illnesses in dogs. Some effective products are available to manage canine angiostrongylosis, but it is prudent to examine further measures for control. More epidemiological and clinical studies are needed to generate the local data if such measures are to be implemented on a sound basis.

Conflict of interest

The author declares this article was written in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Mention of drugs does not imply endorsement by the author or publisher. It is important to read product labels.

Latest news