14 Nov

Managing oncology patients – hospice and palliative care

Image © DimaBerlin / Adobe Stock

Veterinary oncology has seen significant advancements in recent years, with a growing emphasis on improving the quality of life for patients diagnosed with cancer.

As our understanding of animal cancers deepens and treatment modalities expand, it becomes imperative to address the holistic needs of the patient, encompassing not just curative treatments, but also end-of-life care. As veterinary professionals, our role extends beyond mere disease management.

By integrating palliative and hospice care into our practice, we can ensure our patients receive the comprehensive care they deserve – from diagnosis to end-of-life considerations. Embracing these concepts not only elevates the standard of care we provide, but also reinforces the human-animal bond, reminding us of the profound impact our animal companions have on our lives.

This article aims to elucidate the concepts of care, hospice and palliative care in the context of veterinary oncology, emphasising their importance in ensuring the well-being of our animal companions during their cancer journey.

Care

In the realm of veterinary oncology, “care” is a multifaceted term that encompasses a wide range of interventions – from diagnostic procedures and therapeutic treatments to emotional support and end of life considerations.

Care is not just about treating the disease; it is about treating the whole patient. This holistic approach ensures that the physical, emotional and even social needs of the animal are met. It involves a collaborative effort between the veterinarian and the pet owner, working together to ensure the best possible outcome for the patient.

Hospice and palliative care

Often, the terms “hospice” and “palliative care” are used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings – especially in the context of veterinary medicine.

Palliative care refers to the comprehensive care of patients that have a serious illness, aiming to alleviate symptoms without necessarily targeting the underlying disease.

In veterinary oncology, palliative care may involve pain management, nutritional support or interventions to manage complications such as breathing difficulties or digestive issues. The primary goal is to enhance the quality of life for the patient, ensuring it remains comfortable and free from distressing symptoms.

Hospice care, on the other hand, is a specialised form of care designed for animals nearing the end of their lives. It prioritises comfort over curative treatments. Veterinary hospice care may involve home visits, guidance on creating a comfortable environment for the pet and emotional support for the pet owners. The focus is on ensuring that the animal’s final days are peaceful and pain free.

Aims of hospice and palliative care in veterinary oncological patients include:

- management of chronic cancer pain

- nutritional support

- comfortable clinical and domestic asset

- approaches to cancer conversations and decision-making

- explaining and planning

- emotional and psychological support for owners

- caring for the veterinary professionals

Management of chronic cancer pain

Chronic pain is a frequent and distressing symptom in veterinary oncology patients. Whether stemming directly from the tumour itself or as a consequence of therapeutic interventions, pain can significantly diminish the quality of life of the pet. Effective pain management, therefore, is a cornerstone in the comprehensive care of oncology patients.

Cancer-induced pain can arise from the following:

- Tumour growth – as tumours expand, they can exert pressure on surrounding tissues, including nerves, leading to pain. Additionally, some tumours release inflammatory mediators that can sensitise nerve endings.

- Bone metastasis – cancer can disrupt the bone’s architecture, causing pain.

- Neural invasion – some tumours can infiltrate nerves directly, leading to neuropathic pain.

Pain as a consequence of cancer therapy

While therapeutic interventions aim to control or eradicate cancer, they can sometimes be a source of pain themselves:

- Surgery – postoperative pain is a common consequence of oncologic surgeries.

- Chemotherapy – some chemotherapeutic agents can cause peripheral neuropathy, leading to pain and sensitivity.

- Radiation therapy – radiodermatitis, mucositis and generalised soft tissue inflammation lead to pain.

Assessment of cancer pain

Accurate assessment is the foundation of effective pain management. In veterinary medicine, this can be challenging due to the inability of animals to communicate their pain verbally.

Changes in behaviour such as reduced activity, reluctance to move or altered interactions with owners can be indicative of pain. Elevated heart rate or respiratory rate can sometimes be associated with pain.

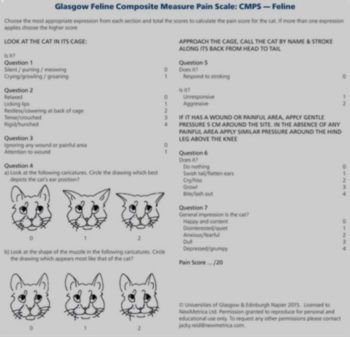

Veterinary-specific pain scales such as the Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scale (Figure 1 and Figure 2) can be employed to quantify pain.

It includes 30 descriptor options within 6 behavioural categories, including mobility. Within each category, the descriptors are ranked numerically according to their associated pain severity, and the person carrying out the assessment chooses the descriptor within each category that best fits the dog’s behaviour/condition.

It is important to carry out the assessment procedure as described on the questionnaire, following the protocol closely. The pain score is the sum of the rank scores.

The maximum score for the 6 categories is 24, or 20 if mobility is impossible to assess.

The total CMPS-SF score has been shown to be a useful indicator of analgesic requirement and the recommended analgesic intervention level is 6/24 or 5/20.

Gentle exercises, massage and cold or heat therapy can aid in pain relief.

In cases where the tumour cannot be completely eradicated, radiation therapy can be employed with a palliative intent. This aims to reduce the tumour size, thereby alleviating pain and improving the quality of life.

Radiation therapy, while therapeutic, can have side effects that necessitate pain management. Radiation dermatitis can be treated with topical therapies such as aloe vera or hydrocortisone, which can soothe inflamed skin. If radiation targets areas with mucous membranes, mucositis can result. Pain relief can be achieved with topical anaesthetics or systemic pain relievers.

Nutritional support

Nutrition plays a pivotal role in the comprehensive care of veterinary oncology patients. The metabolic demands of cancer, coupled with the potential side effects of treatments, often necessitate a tailored nutritional approach.

Cancer cells exhibit a distinct metabolic profile compared to normal cells. Many cancer cells predominantly produce energy through a high rate of glycolysis, followed by lactic acid fermentation, even in the presence of oxygen – this phenomenon is known as the Warburg effect.

Cancer cells often have an increased uptake of glucose to support their rapid proliferation and may have altered amino acid and fatty acid demands, which can impact the overall nutritional needs of the patient. These metabolic alterations can lead to cachexia, characterised by muscle wasting and weight loss, which is commonly seen in cancer patients.

Given the unique metabolic demands of cancer, a tailored nutritional approach is essential and should include high-quality protein to counteract muscle wasting; omega-3 fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory effects and may also inhibit tumour growth; easily digestible carbohydrates, which can help meet the energy demands; and vitamin and mineral supplementation to support overall health, and counteract potential deficiencies.

It is also crucial to monitor the patient’s appetite and weight regularly. Appetite stimulants or feeding tubes might be necessary for patients that are reluctant or unable to eat.

Calculating the resting energy requirement and maintenance energy requirement

The resting energy requirement (RER) represents the amount of energy required by an animal at rest in a thermoneutral environment and is a foundation for determining the overall energy needs.

- RER 2kg to 30kg = BW(kg) × 30 (+70)

- RER less than 2kg and more than 30kg = 70 × BW(kg) 0.75

The provision of more than the RER often is not necessary, except in extreme circumstances, such as when extensive tissue repair is ongoing (mucositis or epithelial sloughing). The increased energy requirement, known as the Illness energy requirement (IER), often is considered to be 1.1 times to 2 times the RER – particularly when transudates or exudates are involved with the repair process, and protein losses are excessive.

Comfort in the clinical and domestic setting

The clinical environment, often characterised by unfamiliar sounds, scents and sights, can be a source of stress for many animals.

Strategies to make the clinical setting more comfortable for oncology patients are important.

Provide designate specific areas in the clinic that are free from loud noises and disturbances, with comfortable, soft and padded bedding. This can be particularly beneficial for patients undergoing long treatments or those who are hospitalised.

Toys, scratching posts for cats and chew toys for dogs can provide distraction, and reduce anxiety.

Regular petting, gentle talking and interaction can provide emotional comfort, and reduce feelings of isolation.

Ensure the clinical setting is neither too cold nor too hot. This is particularly important for patients which have undergone surgeries or those with compromised thermoregulation.

The home environment also plays a pivotal role in the long-term care of oncology patients. Owners should be instructed to make sure their pet has a quiet, comfortable space where it can retreat and rest. This is particularly important for multi-pet households.

Pets with reduced mobility should have easy access to food, water and litter boxes. Ramps can be used to help pets access elevated areas. Owners should closely monitor the pet’s behaviour, appetite and overall demeanour. Any sudden changes should be communicated to the veterinarian.

Just like in the clinical setting, toys, interactive feeders and other enrichment tools can provide distraction, and stimulation. Especially for pets undergoing painful treatments or surgeries, ensure they are handled gently and with care. This includes lifting them with support and avoiding rough play.

Approaches to cancer conversations and decision-making

Increasing acknowledgment for pets as family member is associated with greater expectations by pet owners for the highest quality medical care, in addition to compassionate care and respectful communication.

Today, the responsibilities of veterinary professionals include the emotional health and well-being of clients and their pets. Communication about the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of cancer presents challenges both for veterinary surgeons, and pets’ owners.

From the veterinarian perspective, lack of training, insufficient time, feeling responsible for the patient’s illness, perceptions of failure, unease with death and dying, lack of comfort with uncertainty, the effect on the veterinarian-client-patient relationship, worry about the patient’s quality of life, and concerns about the owner’s and the veterinarian’s own emotional response to the circumstances, are factors contributing to discomfort with this kind of conversation.

Some of these same reasons may account for pet owners’ anxiety during difficult conversations; these also include self-blame and anticipatory grief.

Research in human medicine indicates that breaking bad news, discussion of the prognosis and end-of-life discussions are often suboptimal because of many of these barriers, and a lack of specific training in communication.

Shift from paternalism to partnership in vet-client-patient relationship

Historically, the veterinarian-client-patient relationship was largely paternalistic, with veterinarians doing most of the talking and making decisions on behalf of the patient while the client played mostly a passive role.

Growing client expectations, the strong attachment between people and their pets, and increasing client knowledge demand a swing in communication style from the traditional paternalistic approach to a collaborative partnership.

Partnership or relationship-centred care represents a balance of power between veterinarian and client, and is based on mutuality. It is characterised by negotiation between veterinarian and client, resulting in creation of a joint-venture, with the veterinarian taking on the role of advisor for the owner and advocate for the patient.

The communication about cancer should put an emphasis on engaging clients in discussions, understanding their perspectives and collaboratively deciding on the best course of action; ensuring clients fully understand the implications, risks and benefits of any proposed treatment; acknowledgment that a cancer diagnosis often brings a wave of uncertainty for clients and that medical terms, as well as treatment options and prognostic information, can be overwhelming; lastly, that fear, grief and anxiety can cloud judgement and decision-making.

It is crucial for veterinarians to recognise this uncertainty and provide clear, concise information, coupled with emotional support.

It is essential for veterinarians to acknowledge and manage uncertainty, as well as client expectations: not all outcomes can be predicted with certainty. It is vital to be honest about the unpredictability of certain treatments or the course of the disease, and to have an open dialogue, with regular checks in with clients about their expectations and address any misconceptions.

While some uncertainty is inevitable, the veterinarian should strive to provide as much clarity as possible about what can be expected. Equally, while hope is essential, it is also important to ensure clients have a realistic understanding of potential outcomes.

Quality of life is a cornerstone in oncologic care. Consider physical health, pain levels, appetite and behaviour, and engage clients in discussions about their pet’s quality of life, as they have the most intimate knowledge of their pet’s daily experiences.

Ensure privacy, comfort and empathy when delivering bad news, using clear language, and give clients time to process the information and express their feelings.

When curative treatments are no longer viable, transition to palliative or hospice care should be discussed, ensuring the pet’s owner understands the focus is now on comfort and quality of life.

Bridging knowledge gaps and dispelling myths

As veterinarians, our role extends beyond medical interventions; it encompasses educating and guiding clients through the complexities of their pet’s diagnosis and treatment.

Assessing the client’s starting knowledge

Before delving into detailed explanations, it is essential to assess the starting knowledge of pet owners with open-ended questions, such as: “What do you understand about your pet’s condition?” or “What have you heard about this treatment?”

Pay attention to facial expressions, body language or signs of distress that might indicate confusion or concern.

Information overload can be overwhelming; therefore, information and explanations should be delivered one topic at a time. After each segment, clients should be asked if they have questions or if they would like to further clarify any points. Summarising key points usually reinforces understanding.

Differences in chemotherapy and radiation therapy between pets and human beings

Many clients’ understanding of chemotherapy and radiation therapy is based on human medicine, which can lead to misconceptions. It is crucial to highlight that many pets tolerate chemotherapy better than humans, and while pets can experience side effects, they are often less severe. Hair loss, a common concern due to its prominence in human chemotherapy, is rare in pets, except for certain breeds and specific drugs.

In veterinary medicine, the focus is often on preserving quality of life; therefore, treatments might be less aggressive than in human oncology. Misconceptions about chemotherapy can influence treatment decisions. Addressing the following myths is essential.

Myth: chemotherapy is always painful for pets.

Reality: most pets tolerate chemotherapy well. While some may experience side effects, these are often manageable and temporary.

Myth: chemotherapy will drastically reduce the pet’s quality of life.

Reality: the primary goal in veterinary oncology is to maintain or improve the quality of life. If a treatment adversely affects this, veterinarians often adjust the protocol.

Myth: all pets lose their hair during chemotherapy.

Reality: unlike humans, most pets do not lose their hair. However, some may experience thinning – especially around areas where they receive injections or undergo radiation.

Emotional and psychological support for owners of oncological pets

The journey of a pet through oncological treatment is not just a medical endeavour, but a deeply emotional one. Owners of pets diagnosed with cancer often grapple with a myriad of emotions, from shock and disbelief to grief and sorrow. As veterinarians, our role extends beyond the clinical; it encompasses being supportive and understanding, and offering guidance for these owners from diagnosis to the eventual passing of the pet. The veterinarian should take the time to genuinely listen to the concerns, fears and hopes of pet owners, and reinforce the idea that they are in this journey together, working collaboratively for the well-being of the pet.

Before delivering challenging news, the veterinarian should prepare the owner emotionally, beginning the conversation with phrases such as, “I wish I had better news,” or “This is difficult for me to share”. After discussing details, a concise summary to reinforce understanding and give clarity should be provided.

As the disease progresses and curative treatments might no longer be viable, potential benefits of palliative or hospice care, emphasising comfort and quality of life, should be discussed.

Euthanasia is one of the most challenging decisions for a pet owner and requires clear explanation of the process, ensuring the owner understands it is a peaceful and painless procedure. While veterinarians can provide guidance, it is important to respect the owner’s decision-making autonomy.

The loss of a pet is profound, and grief should be acknowledged and validated. Information on pet loss support groups, counsellors or hot-lines should be provided, as well as a follow-up phone call or note expressing sympathy, which can mean a lot to grieving pet owners.

Caring for veterinary professionals

In veterinary medicine, and more specifically in veterinary oncology, while much emphasis is rightly placed on the patient and the pet owner, a pivotal thread often goes unnoticed: the well-being of the veterinary professionals themselves.

For those individuals, deeply entrenched in the emotional and clinical challenges of oncology, attention must be paid to self-care, support and resilience building.

The emotional weight of veterinary oncology

Veterinary professionals in oncology face unique emotional weight, which can take a significant emotional toll. They regularly deal with terminal diagnoses and end-of-life decisions, pet owners’ desires for positive outcomes, and situations where the best medical decision may conflict with the wishes of the pet owner or financial constraints.

To provide the best care for patients, veterinary professionals must also care for themselves with regular exercise, adequate sleep and a balanced diet, as well as activities such as meditation, journalling or therapy that can help to process emotions and to alleviate stress.

It is essential to set boundaries, ensuring time for rest and personal pursuits outside of work, such as engaging in workshops or courses on emotional intelligence, communication, or grief counselling.

Building resilience, the ability to bounce back from challenges, is pivotal and regular discussions or support groups with peers can provide a platform to share experiences, challenges and coping strategies.

Engaging with seasoned, more experienced professionals in the field can provide guidance, perspective, and support. Institutions and clinics can play a significant role supporting their staff.

Management should regularly check in with staff, ensuring they have the resources and support they need. Encourage and provide opportunities for staff to attend workshops or courses that focus on emotional well-being and resilience, and create spaces within the clinic where staff can take breaks, relax or even debrief after particularly challenging cases.

Nowadays, burnout – characterised by emotional exhaustion, reduced personal accomplishment, and depersonalisation – is a real concern.

Conclusion

The journey through veterinary oncology is a multifaceted one, intertwining the realms of medical science, emotional support and ethical considerations. As we have traversed through the various sections of this article, a few salient themes have emerged.

- Holistic care: the care of oncology patients goes beyond mere medical interventions. It encompasses a comprehensive approach that addresses the physical, emotional and psychological needs of both the patient and the pet owner.

- The power of communication: whether breaking the news of a cancer diagnosis, discussing treatment options or end of life care, effective and compassionate communication stands as a cornerstone in the veterinarian-client-patient relationship.

- The emotional landscape: the emotional weight of a cancer diagnosis is profound not just for the pet owner, but also for the veterinary professionals. Recognising, addressing and supporting these emotions is pivotal in ensuring the well-being of all parties involved.

- Continuous learning and adaptation: the field of veterinary oncology is ever-evolving. As professionals, a need exists for continuous learning – not just in terms of medical advancements, but also in understanding the nuances of client communication, ethical considerations and self-care.

- The human-animal bond: at the heart of all these discussions lies the profound bond between humans and their animal companions. This bond, filled with love, trust and mutual respect, is what drives the quest for excellence in oncological care.

In essence, the care of the oncology patient in veterinary medicine is a journey of science, compassion and collaboration. As we move forward, may we continue to elevate the standards of care, always keeping the best interests of our patients at the forefront, and cherishing the profound relationships that make this journey worthwhile.