3 Nov

Mediastinal mass in a dog – what’s hiding in the middle?

An 11-year-old male, neutered English springer spaniel was presented to the referring veterinarian with a few weeks’ history of lethargy, polyuria and polydipsia.

Work-up included haematology and biochemistry testing; no evidence existed of azotaemia, but total calcium was significantly elevated (3.91mmol/L; reference interval 1.91mmol/L to 3.03mmol/L).

Hypercalcaemia was confirmed by measurement of ionised calcium (iCa), which was also significantly increased (1.91mmol/L; reference interval 1.25mmol/L to 1.45mmol/L).

Since concern existed for possible paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia, the veterinarian performed physical examination (including a rectal exam) and total body imaging studies to investigate for neoplasms commonly associated with hypercalcaemia, such as anal sac adenocarcinoma, lymphoma and thymoma.

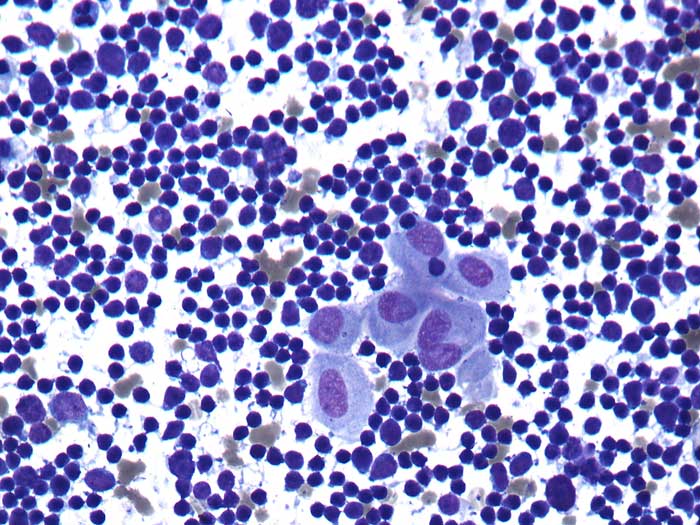

Contrast-enhanced CT revealed the presence of a large cranial mediastinal mass (with a diameter of 11cm) with no obvious invasion of vital structures. An ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirate was performed, and smears were submitted to an external laboratory for review (Figure 1).

The aspirate harvested large numbers of well-preserved nucleated cells on a clear background with only a few red blood cells. A prevalence of lymphoid cells existed – mostly small lymphocytes – with only a few intermediate/large forms seen. Scattered small clusters of polygonal epithelial cells (centre of Figure 1) were noted. These cells showed moderate amounts of basophilic cytoplasm with defined borders.

Nuclei ranged from round to oval, and had granular chromatin and small visible nucleoli. Very rare binucleated cells were seen. Anisocytosis (cell size variation) and anisokaryosis (nuclear size variation) were mild to moderate. Rare blood derived leukocytes – mostly neutrophils – were also noted.

Diagnosis

The presence of lymphoid cells – mostly small lymphocytes – admixed with a few clusters of epithelial cells was consistent with thymoma.

Follow-up

A ventral midline thoracotomy was performed and the mass – which was adhered to, but not invading the major vessels and pericardium – was dissected free. Histopathological examination of the excised mass confirmed the previous cytological diagnosis of thymoma. The dog recovered from the surgery and within two weeks had resolution of hypercalcaemia, polyuria and polydipsia. No signs of recurrence were reported in the first year follow-up after surgery.

Insight

Thymoma is a neoplasm originating from the thymic epithelium and represents the second most common cranial mediastinal tumour in dogs after lymphoma. Even though the thymus is primarily active in very young animals, thymoma is typically diagnosed in older medium to large-breed dogs. Clinically, most patients present with respiratory signs (for example, coughing, tachypnoea and dyspnoea) related to the mass itself and/or secondary pleural effusion.

General signs reported include reduced appetite, weight loss, exercise intolerance and lethargy. In severe cases (often invasive), precaval syndrome (presenting as oedema of the head, neck and forelimbs) may also occur, secondary to obstruction of venous and lymphatic drainage.

Several paraneoplastic syndromes have been described with thymoma, including hypercalcaemia, myasthenia gravis and, occasionally, concurrent immune-mediated disease.

Diagnosis can be achieved by cytology and relies on the presence of clusters of epithelial cells admixed with lymphoid cells – mostly small. Granulated mast cells are also often observed.

When a definitive cytological diagnosis is not possible (for example, hypocellular sample, absence of epithelial cells), further testing should be considered, including the following.

Histopathology

Surgical biopsy with histopathological examination may allow a definitive diagnosis of thymoma – especially in lymphocyte-rich forms that may appear similar to small cell lymphoma and may result in no epithelial cells seen on cytology.

However, this diagnostic investigation is invasive and sometimes may lead to non-diagnostic or inconclusive results – in particular when the biopsy is very small.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry is a useful and relatively non-invasive test as it only requires fine-needle aspiration. A study has shown that in dogs flow cytometry may help differentiate lymphoma from thymoma.

Thymomas consist of greater than or equal to 10 per cent lymphocytes co-expressing cluster of differentiation (CD)4+ and CD8+ (a phenotype that is characteristic of thymocytes), whereas lymphomas are characterised by neoplastic cells that express either CD4+ or CD8+ markers.

Main limitations of this technique include the need for analysing the sample within 24 hours from time of collection and the fact lymphomas co-expressing CD4+ and CD8+ are not common, but may occur.

PCR for antigen receptor rearrangements

PCR for antigen receptor rearrangements (PARR) is another useful tool to differentiate thymoma from lymphoma. It is a non-invasive procedure, as it can be performed on almost any sample containing cells, including pre-stained cytology smears. Aspirates from thymoma show a polyclonal lymphoid component, whereas this tends to be monoclonal in lymphoma.

Biological behaviour, treatment and prognosis

Differentiation from mediastinal lymphoma is crucial from both therapeutic and prognostic points of views. The definitive therapy for thymoma is surgical removal. A study from 2013 evaluating 116 dogs undergoing surgical excision of thymomas determined a median survival time of 635 days (Robat et al, 2013). Mediastinal lymphomas are usually approached with multiagent chemotherapy protocols.

A recent publication from the University of California, Davis on 42 dogs showed an overall survival of 194 days only for dogs receiving treatment with a cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone protocol (Moore et al, 2018).

Take-home message

Thymoma and lymphoma are the most common neoplasms developing in the mediastinal space in dogs. Differentiation between the two is very important from both prognostic and therapeutic points of views.

A final diagnosis can often be achieved by cytology. When this is not possible, additional testing – including histopathology, flow cytometry and/or PARR – should be considered to investigate it further.