3 Dec 2018

Minimising ketosis in the calved cow

Paddy Gordon looks at measures to prevent or minimise incidences of this metabolic disease in dairy cattle.

What does success look like for dairy farmers? Like all businesses, a need to generate profit exists. However, on a day-to-day assessment, success is often measured in milk yield.

Milk yield is seen as an indicator of cows reaching potential, with nutrition and management meeting the cow’s needs.

Dairy vets work with their farmers in many ways to improve milk yield, but need to be aware of and communicate the time lag before the impact of advice or intervention will be seen – for example, advice on improved genetic selection will not be evident as improved milk yield for three years; the time to conception – with improved genetics, gestation length and age at first calving, adding up to at least three years.

Many other aspects of vet advice show a delayed response in milk yield. Improved fertility management will not result in milk yield gains for nine months. Tackling infectious disease, such as Johne’s disease or bovine viral diarrhoea, will create long-term gains for the farm, but milk yield response will be incremental.

Ketosis control and transition cow management offer the dairy vet a more immediate opportunity to influence outcome, and milk yield, as a marker of success. This key period encompasses the dry period through to around 30 days calved, and about 90 days in duration. Therefore, putting in place any necessary changes should give results in a similar period.

If we consider what success looks like, it is maximising dry matter intakes post-calving as this will drive milk yield, ensuring healthy cows perform to potential, but is also an indicator of good health. Getting management, housing and nutrition right will reduce the incidence of sick cows, which can be as high as 50% where intakes will inevitably be poor and milk yield below target.

For the dairy cow, calving is the most critical time on the production cycle. It is human nature to attribute the poor performance that may follow a metritis to the retained cleansing. However, we need to consider the underlying cause and our opportunity to prevent or minimise risk. When we consider the range of conditions seen in the periparturient period – such as dystocia, retained foetal membranes, metritis, mastitis and milk fever, ketosis and displaced abomasum – common underlying causes of poor metabolic health exist (energy, macro-mineral or immune function).

The conditions are interlinked and poor function in one aspect can result in development of another condition; for example, mastitis can result in inappetence, increasing the risk of ketosis. Ketosis should be regarded as the “gateway disease” and a key performance indicator of energy situations.

Ketosis has the advantage of being easy to measure, with cow-side tests available. It can be measured between 7 and 21 days after calving, but measurement between days 4 and 7 give the greatest opportunity for prompt identification of ketosis and corrective action to take place. Beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) is measured, and accurate quantitative blood tests or semi-quantitative milk tests exist. Selection will depend on personal preference, with a blood test offering greater accuracy, while a milk test is simple and convenient, allowing samples and testing to be carried out by herdsmen.

The threshold for the impact of elevated BHB differs between studies, but sources agree a blood level of more than 2.6mmol/L indicates clinical ketosis. Levels more than 1.0mmol/L are associated with increased disease incidence – 13.6 times greater odds of developing displaced abomasum when compared to lower values – and 4.7 times greater risk of developing clinical ketosis. Again, this would give justification to early recognition and treatment to reduce incidence and clinical impact, with the potential to also reduce subsequent culling.

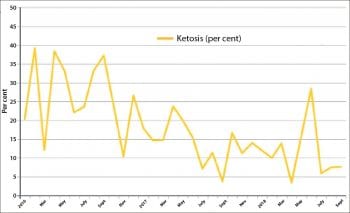

Studies have found an incidence of ketosis in the UK of around 30% and 40% in the US, with wide variation between farms and over time.

Affected cows should be clinically examined to determine if other conditions are present, as ketosis can be secondary to metritis; for example, elevated ketones should be treated with 300ml propylene glycol daily by mouth for three to five days. Vitamin B12 has been shown to reduce recovery rates, and oral fluid therapy may assist recovery. Cows’ appetite and milk yield should be closely monitored for the following week in case of treatment failure or unrecognised disease.

Monitoring systems

The impact of ketosis as a gateway disease and the relatively high incidence justify putting monitoring systems in place on farm. Testing all fresh-calved cows at four to seven days post-calving ensures any issues are recognised promptly and can be treated when necessary. This approach is easily adopted on the larger housed, high-input herds, where standard operating procedures are in place. Alternatively, strategic testing can be carried out. This may be at key times of the year, such as with seasonal calving herds, where we find more issues with late calving animals – as these will tend to be older and fatter, with less control of dry cow feeding, particularly if grazed.

Testing can also be adopted in response to a problem and confirm suspicions. The danger with this responsive approach is the problem can be missed for a considerable time. Repeated measurement is required. Some farms may be reluctant to test due to time pressure or a failure to recognise ketosis as a significant issue for the farm. In this case, sampling suspect clinical causes can increase awareness.

Alternatively, proxy measures can be used. These proxy measures can be increased disease incidence (transition failures), such as left displaced abomasum (LDA) cases. As this condition has an incidence of 1% to 2% then cases will occur sporadically and sometimes in clusters. Cases can be attributed to individual reasons, such as lameness, rather than herd factors, and this tends to delay recognition and assessment.

Milk constituents can also be used and include milk protein percentage, total protein yield or protein intercept. Reduction in milk protein levels can be used as an indication of declining energy status and used to justify further investigation. Focus on early lactation animals will increase sensitivity. Fatty acid profiling is a developing area and may provide further information.

Reducing ketosis

Attention needs to be given to housing, management and nutrition to comprehensively review all the impacts that contribute to ketosis risk. Elanco Animal Health has produced support materials for assessing transition health (www.vital90days.co.uk), including a paper-based “Health start checklist” and a tablet-based app.

Factors used to identify the risk of disease in our target population of cows from dry off to 30-days calved include body condition and health.

Body condition is crucial, with both fat and thin cows being associated with increased ketosis risk. Fat cows are often a product of poor transition health and poor subsequent milk yield or poor fertility outcomes.

Unless addressed, fat cows are at risk of repeating the pattern of underperformance as they are at high risk of ketosis and health problems in early lactation. Kexxtone is licensed for use in at-risk cows, including fat cows, as results indicate a 75% reduction in ketosis. Kexxtone boluses contain a slowly released ionophore antibiotic that will promote the ruminal synthesis of propionate. Treatment is three to four weeks prior to due calving date. For cows not yet in calf, ceasing to breed after 200 to 250 days calved will help to reduce the likelihood of further fat cows and break the cycle of “fat cow to thin cows to fat cows”.

Thin cows can be the result of an underlying issue, such as lameness or Johne’s disease. Improved disease control is essential to reduce ketosis risk. On a visit by the author to the US, a vet identified lame dry cows as a major concern for health and welfare, as these cows will be high risk for poor intakes and ketosis.

The new generation of cow-monitoring activity meters/accelerometers are used in research to identify cows’ behavioural changes prior to calving. It appears cows predisposed to ketosis stand for fewer hours prior to calving, with reduced dry matter intakes and lower milk yield postpartum. The cause of the increased time laying needs to be understood, but offers the potential for early intervention, if activity meters are in place and algorithms developed to flag affected cows. Further research is required to identify the underlying reasons for this behavioural change, but we can speculate it could be metabolic status and liver function, or unrecognised disease, or factors such as pecking order and stress.

Housing needs are, as always, to maximise comfort, with poor comfort associated with reduced intakes. Crucial housing factors include cow comfort, feed access and stable social groups. Far-off dry cows (those from dry off to three weeks before calving) may be grazed in straw yards or cubicles. Comfort is key for the heavily pregnant cow, along with adequate space or stocking rate.

For housed cows, issues often arise when dry cow numbers fluctuate, and periods when numbers exceed a 90% stocking rate for cubicles or are less than 10m2 of straw yard space. Feed access should be a minimum of 75cm at all times and group changes made only once a week. The timing of any move to the transition pen must take place at least 18 days before calving to allow cows adequate time to settle in the new group.

Nutritional requirements are to feed a so-called “Goldilocks diet”, indicating not too much and not too little of the key ingredients of energy, protein and fibre. Dry cow diets can be a single ration (high fibre low energy) fed throughout the dry period. This is typically formulated with high levels of straw (5kg to 7kg) and can prove effective as little risk of milk fever exists, and good control of energy in the early dry period. A risk of poor intakes exists if straw is unpalatable, or low protein levels can result in excessive weight loss.

When two diets are fed, a transition ration is fed in the three weeks prior to calving, to acclimatise the cow to the milking diet. This can also work well, but care must be taken in the early dry period, particularly if dry cows are grazed, to avoid excess energy intakes. Cows must have sufficient time to settle on the close-up ration, typically 21 days, with a minimum of 18 days. Once established in the close-up group, target feed intakes are around 13kg dry matter.

As important is the presentation and access to the diet, with no spoilage, feed pushed up frequently and feed access unrestricted. To ensure water access does not restrict intakes, 10cm of water trough space is also required.

Case example

A 500-cow dairy has adopted a regular monitoring programme, with every cow assessed for ketosis at day four after calving.

Testing is carried out by the herdsman using the Precision Xtra meter. Cows with a BHB level greater than 1mmol/L are given 300ml oral propylene glycol daily for three days, and their health and production closely monitored.

In 2016, initial results showed a ketosis level typical of UK dairy herds of 31% (Figure 1). Initial action was taken to address underlying lameness through prompt attention and corrective trimming. Any fat cow was administered with a Kexxtone bolus three weeks before due calving date. Chronic lame cows and cattle testing positive for Johne’s disease were culled. Breeding was ceased for all cows more than 250 days calved and not pregnant.

Housing was altered from straw yards for dry cows, with fresh cows joining the main milking herd to a new cubicle set-up with deep sand cubicles for transition cows, with stocking rate kept below 85% to allow at least 70cm feed space. Cows were moved into an adjacent straw yard around one week before calving as they started to show udder changes, so they had good space and comfort to calve. This group typically contains up to 10 cows, with plenty of feed space.

After calving, cows moved into a fresh group where they were bedded in deep sand cubicles. Fresh-calved cows remained in this group for up to 30 days and could be monitored closely. Feed space is good and the group kept close to the milking parlour, allowing for regular monitoring.

Diet challenges will always exist due to changing forage quality. Regular monitoring of forage quality was used to highlight any issues, such as poor palatability and variable intakes. These are not always easy to address as any forage will need to be fed, but risks were addressed by ensuring good forage/fibre proportions in the diet, and the use of supplements, such as mycotoxin binders and rumen buffers, when required.

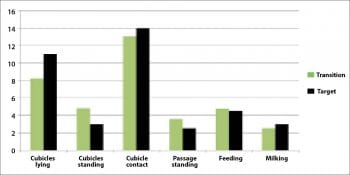

Cow behaviour was assessed using a time-lapse camera. The camera can be set up to take pictures every 10 minutes over a 24-hour period. This allowed monitoring of the fresh cow sheds, with a review of cow behaviour and time budgets (Figure 2).

A number of issues were apparent from this assessment. While cows were found to be out of the cubicles for a very short time, a period occurred when fresh feed was not available each morning, resulting in a peak feeding period when it was presented. Changes were made to feeding routines, with blends mixed prior to diet mixing to allow cows to be fed each morning soon after milking and greater efforts were made to feed this fresh group to excess, with around 5% of feed surplus to requirements. While housing was assessed as good, some heat stress was apparent, based on reduced lying times. To address this, skylights were painted over.

The overall impact of these changes has been to reduce ketosis incidence over a two-year period from 31% to 8% (Figure 1), although a short-term increase has been associated with heat stress in June. The impact of minimising this gateway disease has been to reduce the incidence of LDAs from 5% to 2%. This shows the value of a comprehensive understanding of ketosis and its causes – and the effectiveness of veterinary intervention.

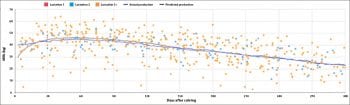

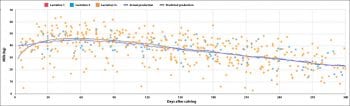

The impact on milk yield has been an increase in peak yield from 44kg to 48kg (Figure 3 and Figure 4) – success for the farmer and the vet building a working partnership with his clients.

Latest news