14 Jan 2020

Mitral valve disease: timeline of a degenerative condition in dogs

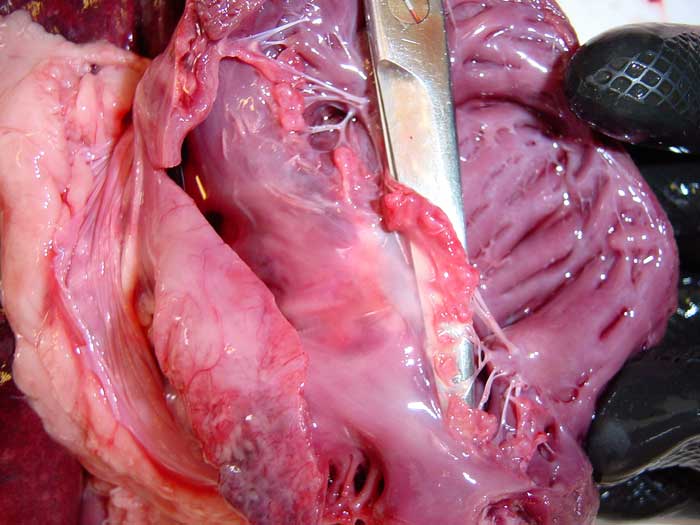

Figure 1. Postmortem specimen from a dog showing changes consistent with myxomatous mitral valve disease. The mitral valve leaflets are lifted by the surgical scissors, and appear thickened and distorted, with nodules merging on the free edges. Chordae tendineae are also affected, and appear elongated and thickened.

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) – or, simply, “mitral valve disease” – is a chronic degenerative disease causing deformation of the mitral valve with subsequent malapposition of its leaflets, which allows blood to flow backwards into the left atrium during cardiac contraction (mitral regurgitation), producing a typical heart murmur.

The tricuspid valve is also commonly affected, with an associated tricuspid regurgitation; therefore, some clinicians prefer to refer to this condition as atrioventricular valve degeneration. The disease primarily affects geriatric, small-breed dogs, but can also be diagnosed in larger breeds.

This article covers different aspects of the aetiology, pathophysiology, clinical signs, diagnosis and prognosis of this important cardiac disease, as well as recommendations for medical and surgical management.

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is the most common cardiac disease in dogs, and represents the primary cause for congestive heart failure (CHF) and cardiac-related death1.

The disease is more prevalent in small-breed dogs, although it can also be observed in large breeds. Some small breeds are reported to have an incidence close to 100% over a dog’s lifetime.

Predisposition and aetiology

Among small-breed dogs, cavalier King Charles spaniels are particularly predisposed – and this breed seems to have a genetic predisposition to MMVD.

Indeed, early clinical studies have shown a high proportion of dogs of this breed develop mitral valvular insufficiency at a young age, as originally reported by the first observation from Peter Darke in 19872.

The aetiology of MMVD is still unknown and remains under investigation; however, it is thought some of the following causes may potentially be implicated.

Endocarditis

It was previously believed MMVD was caused by endocarditis secondary to bacteraemia, frequently thought to originate from the oral cavity in cases of dental disease.

However, endocarditis is relatively rare in dogs and typically affects large-breed dogs, rather than small-breed ones.

Wear and tear

This hypothesis has been advocated for several years, explaining the slowly progressive changes of the valve leaflets as a result of their repeated impact, especially in the areas of apposition.

However, not all adult dogs are affected by MMVD; therefore, some other predisposing factors may be necessary for the development of the disease in certain individuals.

Collagen abnormalities

Abnormalities of matrix components (for example, collagen) have also been suggested to predispose to MMVD.

In humans, for example, mitral regurgitation (MR) occurs in association with a variety of connective tissue disorders and thoracic deformities (for example, pectus excavatum and shallow chest). A similar association seems to exist in dachshunds, but little is known about other canine breeds.

These abnormalities may lead to abnormal valve motion, such as prolapse, and increase the shear stress imposed on the leaflets by abnormal leaflet apposition or the regurgitant flow.

Endothelial damage

Damage to the valvular endothelium may be another important factor in the pathogenesis of MMVD, because it may lead to an imbalance in local growth factors produced by endothelial cells, as suggested by the association between disease severity and expression of endothelin receptors.

Furthermore, collagen may become exposed to blood in valvular areas in which the endothelium is damaged – this exposure is expected to promote thrombosis, although this represents a rare complication in dogs.

Serotonin production

Some recent experimental evidence seems to support a possible role of the serotonin signalling pathway triggered by altered mechanical stimuli in the disease development.

According to this hypothesis, the activation of tension mechanosensors is associated with a local increase of expression of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1), which, ultimately, promotes the synthesis of serotonin at the level of the valve leaflets3.

Pathophysiology

Anatomical changes

In MMVD, the mitral valve leaflets, which appear thin and translucent in healthy dogs, become thickened and distorted, often bulging towards the left atrial lumen (prolapse).

With disease progression, nodular lesions appear on the free edges of the mitral valve leaflets and can eventually merge into larger nodules – causing a plaque-like deformity, often involving proximal portions of the chordae (Figure 1).

Valvular prolapse and regurgitation

The anatomical changes of the mitral valve result in mitral valve prolapse (a portion of the valve leaflets protrudes towards the atrium), and incapacity of the valvular edges to coalesce and seal the atrioventricular annulus during systole.

This abnormality causes the valvular regurgitation and the presence of a heart murmur in these patients.

Chamber dilation

Depending on the severity of the regurgitation – namely, the quantity of blood that flows back into the atrium – the disease may cause anatomical changes of the cardiac chambers, such as atrial dilation and, eventually, ventricular enlargement (eccentric hypertrophy).

Left atrial and ventricular dilation – often referred to as cardiomegaly – cause progressive tracheal elevation and, in some patients, compression of mainstem bronchi, resulting in stimulation of the coughing mechanoreceptors (typical dry cough often described by owners as “honking” or “bone in the throat” cough).

However, this phenomenon seems to occur mainly in geriatric patients affected by concomitant airway diseases – such as bronchomalacia, tracheal collapse and/or chronic airway inflammation.

Unfortunately, widespread assumption exists that a dog with a murmur that coughs must be in CHF. This concept is dangerously misleading, since the primary cause of cough in these patients is nearly invariably the activation of coughing receptors facilitated by underlying respiratory disease, with the stimulation of cough receptors being further exacerbated by cardiomegaly compressing their airways.

Therefore, these dogs start coughing some time before the onset of CHF and this can mistakenly prompt diuretic treatment, sometimes at high doses due to the inconsistent clinical response, and the inevitable side effects of chronic diuresis (polyuria/polydipsia, chronic dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and potential hypotension and kidney damage)4,5.

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation

In patients with MR, as long as the left atrium dilates to accommodate the regurgitant blood volume, atrial pressure does not increase and, therefore, pulmonary oedema does not develop.

However, the reduced stroke volume – and resultant reduced cardiac output – is sensed by baroreceptors distributed at the level of the carotid sinus and aortic arch, and by the cells of the juxtaglomerular apparatus/macula densa system in the kidney.

This causes the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic system, resulting in salt and water retention, vasoconstriction and increased heart rate (compensatory phase).

The resultant increase in blood volume increases venous return to the heart, resulting in ventricular volume overload, which eventually causes ventricular dilation (eccentric hypertrophy).

End point of chamber compliance and venous congestion

With the progression of the disease, the capacity of the ventricle to accommodate volume overload decreases and ventricular diastolic pressure increases. Diastolic atrial pressure also increases because the atrium and ventricle communicate in diastole. The left atrium and pulmonary veins also communicate, and no valves are present in-between.

Therefore, increased atrial pressure causes increased pulmonary venous and capillary pressure, which will eventually result in pulmonary oedema (CHF) – resulting in the typical clinical signs of tachypnoea/dyspnoea.

Pulmonary hypertension

In severe advanced cases, the pulmonary arterial pressure will also increase – resulting in pulmonary arterial hypertension, right ventricular pressure overload and, eventually, right-sided heart failure (jugular pulsation, liver congestion, ascites).

Arrhythmias

Left atrial dilation may also cause the development of atrial arrhythmias characterised by premature atrial contractions and, in more advanced and severe cases, atrial fibrillation.

Left ventricular dilation can cause reduced myocardial perfusion (myocardial ischaemia) with consequent ventricular arrhythmias – usually characterised by uneventful ventricular premature complexes, but occasionally developing into more severe ventricular tachycardia or even ventricular fibrillation and sudden death.

Myocardial infarction and fibrosis

Small, often microscopic, intramural myocardial infarctions are common findings secondary to myocardial ischaemia. These changes can also affect the papillary muscles, contributing to the misalignment of the valvular architecture.

Less frequently, macroscopic infarctions are observed postmortem. The coronary lesions responsible for the myocardial ischaemia resemble the changes seen in myxomatous valves (hyaline or fibromuscular intramural arteriosclerosis). Intramural arteriosclerosis and myocardial infarcts can predispose to sudden death in 20% of affected patients6.

Interestingly, the degree of arteriosclerosis and fibrosis is associated with decreased systolic function and survival time in dogs with MMVD and CHF.

Jet lesions

The regurgitant jet may also cause scar lesions (“jet lesions”) on the atrial endothelial surface.

In severe cases, massive enlargement of the atrium and scar lesions can cause atrial tears, with consequent bleeding into the pericardial sac (acute or subacute haemopericardium).

Left atrial rupture with acute cardiac tamponade is an uncommon, but catastrophic, sequel.

Chordae tendineae rupture

Although, in one study, chordae tendineae rupture (CTR) was associated with a higher overall survival time than previously believed7, this – in the author’s experience – is often accompanied by a significant progression of the disease and rapid deterioration of the clinical condition.

Chordae associated with mitral valve leaflets affected by myxomatous degeneration tend to be thicker, heavier and elongated, and eventually fail in their mechanical task of holding the valve in place during systole – causing a portion of the valve to prolapse or even “flail” into the left atrium.

The clinical outcome of CTR is affected by several factors – including the type and location of chordal rupture (for example, a major versus minor chordae); the geometry and size of the mitral valve orifice; the size, function, and compliance of the left atrium (LA); the status of left ventricular function; and heart rate.

Diagnosis

Presumptive diagnosis of MMVD is relatively straightforward, based on signalment (geriatric small-breed dog) and the presence of a newly developed systolic heart murmur with a point of maximum intensity over the left apex (Audio 1).

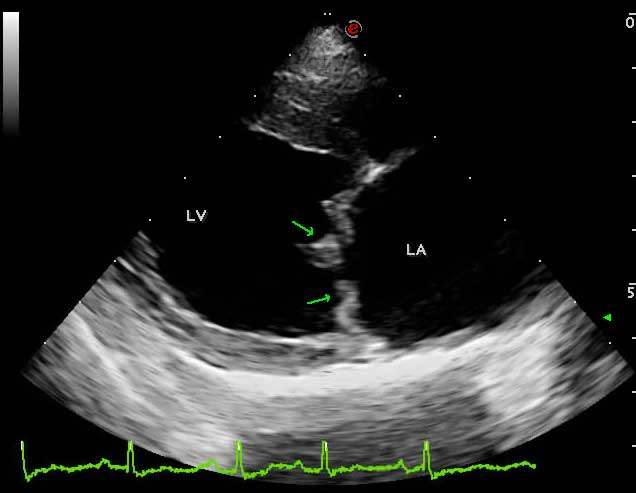

However, definitive diagnosis requires the visualisation of mitral valve lesions on echocardiographic examination (thickened, redundant and distorted leaflets; Figure 2) and direct evaluation of valvular incompetence (MR) by colour and spectral Doppler (Video 1).

Natural history of the disease

MMVD can be viewed as a progressive disorder, with its initiation signalled by the onset of MR. This onset tends to be gradual – sometimes insidious – and will eventually produce a decline in the pumping capacity of the heart.

In most cases, patients will remain symptom-free for many years following the initial decline of the pumping capacity and develop clinical signs only after the dysfunction has been present for some time.

Although the precise reasons why patients with ventricular dysfunction remain asymptomatic is not completely clear, one potential explanation is that a number of compensatory mechanisms are activated after the onset of cardiac injury and depressed cardiac output, and appear to modulate ventricular function within a physiological/homeostatic range – such that the functional capacity of the patient is preserved or only minimally depressed.

The physiological mechanisms observed during the progression of MMVD include the activation of the adrenergic nervous system and RAAS, oxidative stress, increased secretion of antidiuretic hormone, neurohormonal activation in the peripheral vasculature, release of natriuretic peptides, reduction in muscle mass, and abnormalities in muscle structure, metabolism and function.

However, it is important to recognise the fact compensatory mechanisms in MMVD will eventually lead to a series of structural changes within the heart, referred as “cardiac remodelling”. This leads to disease progression, despite the activation of the compensatory mechanisms.

The most recent American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of MMVD in dogs8 represent a very useful tool to stage the progression of the disease.

According to this approach, the disease is expected to progress from one stage to the next, following the natural course of the disease. The ACVIM staging system is also particularly useful for therapeutic decision making, as summarised in Table 18.

| Table 1. Summary of the 2019 American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) consensus staging criteria and therapeutic recommendations (modified by the author) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage A | Stage B1 | Stage B2 | Stage C | Stage D | |

| Description | Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is not present, but the patient is at higher-than-average risk for developing the disease (for example, cavalier King Charles spaniels). | MMVD is present. No evidence of cardiac remodelling on echocardiography or thoracic radiographsa. | MMVD is present. Evidence of cardiac remodelling on echocardiography or thoracic radiographsa. | MMVD is present and severe enough to have caused at least one episode of congestive heart failure. | MMVD is present and severe enough to have caused refractory congestive heart failure. |

| Conservative management | None | None | • Sleeping respiratory rate monitoring • “Cardiac” dietb • Regular exercisec |

• Sleeping respiratory rate monitoring • “Cardiac” dietb • Regular gentle exercise |

• Sleeping respiratory rate monitoring • “Cardiac” dietb • Regular gentle exercise |

| Therapeutic management | None | None | • Pimobendan • Surgical interventiond • Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors? • Spironolactone? |

• Furosemide or torasemide • Pimobendan • Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors • Spironolactone • Surgical interventiond,? |

Same as stage C, but further interventions are often necessary to control clinical signs. |

| Rechecks | Annually by auscultation. | Annually by echocardiography (or radiography if echocardiography is unavailable). | Biannually by echocardiography (or radiography if echocardiography is unavailable). | Ideally every three to four months. | Whenever needed to stabilise the clinical condition. |

| a Criteria for inclusion in group B2 include murmur intensity greater than or equal to 3/6; left atrium:aorta ratio greater than or equal to 1.6 on echocardiography; left ventricular internal diameter in diastole, normalised for bodyweight, greater than or equal to 1.7 on echocardiography; and breed-adjusted radiographic vertebral heart score greater than 10.5. | |||||

| b Mild dietary sodium restriction, and provision of a highly palatable diet with adequate protein and calories for maintaining optimal body condition. | |||||

| c Regular gentle lead walks are believed to reduce the progression of muscle wasting and sarcopenia causing exercise intolerance and lethargy. | |||||

| d Mitral valve repair is possible, although financial affordability and availability of specialist centres in the area may represent limiting factors in some cases. | |||||

| ? Combined administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and spironolactone in stage B2 is not included in the ACVIM consensus; however, it has been demonstrated this intervention can significantly reduce the progression of cardiac remodelling in dogs with MMVD (stage B2). | |||||

Prognostic indicators

Inevitably, following diagnosis of MMVD, the question of long-term prognosis arises.

Preclinical MMVD represents a relatively benign condition in dogs; however, this stage of the disease cannot be described as homogeneous, because affected dogs present with heterogeneous outcomes. Therefore, it is very important for clinicians to be familiar with prognostic parameters and their significance.

Risk factors associated with rapid progression of MMVD include age, degree of MR (as indicated by murmur intensity and/or jet size assessed by colour Doppler echocardiography), and severity of valvular changes.

Variables that can predict the onset of CHF include – but are not limited to – LA size (LA:aorta ratio greater than 1.7), left ventricular end-diastolic (greater than 100ml/m2) and end-systolic (greater than 30ml/m2) size, and transmitral flow pattern (peak velocity of early transmitral filling greater than 1.2m/s).

Vertebral heart score (VHS) on thoracic radiographs, blood concentrations of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, heart rate and heart rate variability have also been reported as important prognostic variables1,9.

Conservative management

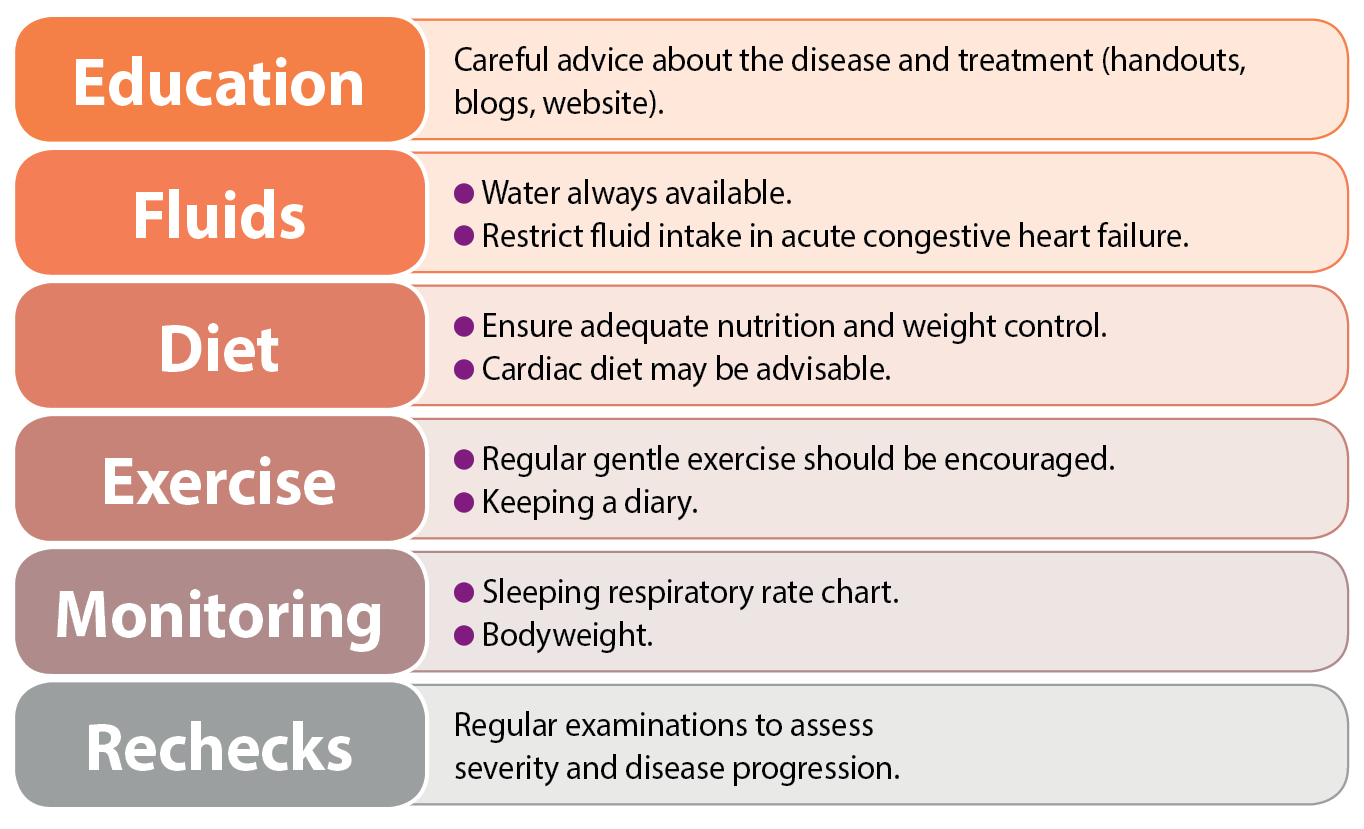

Effective counselling and education of pet owners is important, and may enhance long-term compliance with management strategies.

Simple explanations about the nature of the disease and signs of heart failure – including details on drug and other treatment strategies – are invaluable. Emphasis should be placed on self-help strategies for each dog, and their carers can be instructed how to monitor, for example, their pet’s weight, respiratory rate and exercise activity (Figure 3).

Medical Management

The latest ACVIM guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of MMVD in dogs8 have clarified some of the controversies around the ideal medical management of these patients.

Although it is important to acknowledge the fact dogs with MMVD may present a variable degree of severity – even among individuals at the same stage of their disease – the correct diagnosis and classification/staging facilitates a relatively immediate decision-making process.

Dogs affected by MMVD are mostly managed by administering drugs with the purpose of prolonging survival time. A summary of these interventions is reported in Table 1.

Among the novelties of the ACVIM consensus is the recommendation of administering pimobendan to dogs in stage B2, following the results of the “EPIC Study”, which demonstrated that administration of pimobendan in asymptomatic dogs with evidence of cardiac remodelling (characterised by normalised left ventricular internal diameter in diastole greater than or equal to 1.7; LA:aorta ratio greater than or equal to 1.6 on echocardiography; VHS greater than 10.5; Table 1) can significantly postpone the onset of CHF10.

Another novelty is the use of spironolactone, which has been recommended for the treatment of MMVD patients with signs of CHF (stages C and D)8.

A study has also demonstrated the administration of combined benazepril and spironolactone can reduce the progression of cardiac remodelling in dogs with MMVD stage B2, although this medication failed to extend the asymptomatic phase in that dog population11.

Surgical management

Surgical mitral valve repair is available in some specialist centres. This type of surgery requires cardiopulmonary bypass to perform a left atriotomy, direct visualisation of the mitral valve, mitral annuloplasty and replacement of chordae tendineae, with the aim of restoring leaflet coaptation and diminishing – or even abolishing – MR.

The technique requires a well-trained and experienced team, specialist equipment and state-of-the art facilities.

Although the outcome of mitral valve repair can certainly justify the surgical approach of MMVD, financial affordability and availability of specialist centres in certain areas may represent limiting factors.