10 Dec

Oncological staging and planning of surgical companion animals

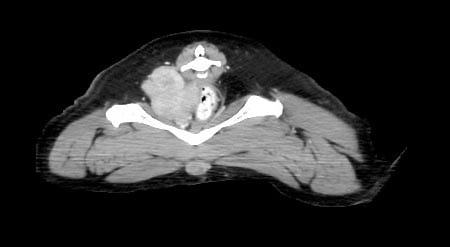

Figure 1b. Cervical lymphadenopathy (bilateral enlargement of the mandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes) in a 10-year-old domestic shorthair cat with rhinopharyngeal large cell lymphoma.

Staging represents the assessment of the anatomical extension of a neoplasm, and allows vets to define – in a standardised way – how voluminous and widespread the tumour is at the time of diagnosis.

It is crucial in the management of veterinary oncological patients, as it provides essential information to define the local, regional and distant extent of disease, formulate a prognosis and develop an overall therapeutic plan based on the stage reached by the neoplastic disease, and for the evaluation of treatment results.

Staging cannot disregard the knowledge of the histotype of the specific tumour investigated, since different tumours have different biological behaviour, different metastatic mode – for example, lymphatic, haematogenous diffusion, for continuity and by contiguity – and different target organs for metastasis.

Cancer staging can be divided into clinical, surgical and pathological staging.

Clinical staging describes the anatomical extent of a tumour at a set point in time and is based on all available information obtained before treatment. This stage may include information about the tumour obtained by physical examination, and instrumental investigations such as blood tests, radiological examination, biopsy and endoscopy. It takes account of the size of a neoplastic process, how deeply it penetrates adjacent organs, whether it has metastasised to regional lymph nodes and how many lymph nodes are affected, and whether the tumour has spread to more distant organs.

Thanks to the development of modern imaging techniques, it is often possible to obtain cytological or histological diagnostic samples by endoscopic or CT-guided sampling without surgery.

Surgery assumes a diagnostic role when non-invasive techniques are inapplicable for the site of the lesion, or ineffective in guaranteeing the quality of samples due to the prevalence of necrotic material or for the small size of the neoplastic lesion.

Surgical staging is particularly important when the pathological outcome can modify the extension of surgery (surgical dose) or the type of therapeutic approach.

Pathological staging represents a refinement of the aforementioned staging modalities, and has important prognostic and therapeutic implications. This type of stage is considered the true stage because information is gained by direct examination of the tumour microscopically by a pathologist after it has been surgically removed, whereas information in the clinical staging is gained by indirect observation of the tumour in situ. Pathological staging allows evaluation of the radicality of excision of the tumour (in case of radical surgery) by evaluating the histotype, margins of resection and the presence of possible lymph nodal involvement.

Because they use different criteria, clinical and pathological staging often differ. Pathological staging is usually considered more accurate because it allows direct examination of the tumour in its entirety, while clinical staging is limited by the fact information is obtained by making indirect observations of a tumour still in the body. However, clinical and pathological staging often complement each other. Clinical staging is, therefore, essential for the choice of therapy, while pathological staging provides valid information to formulate a prognosis and useful indications on whether to carry out adjuvant therapies.

Not every tumour is treated surgically, so pathological staging is not always available. Also, surgery is sometimes preceded by other treatments – such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy – that shrink the tumour, so the pathological stage may underestimate the true stage.

It is important to underline that, once established, clinical staging can no longer be changed – even if the data provided from surgery (for example, prophylactic lymphadenectomy) indicate a more advanced stage.

Tumour, node, metastasis system

Different clinical staging systems have been described. The extent of neoplastic disease has been internationally standardised through the World Health Organization (WHO) tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification system.

The TNM system is the most widely used cancer staging system in human medicine – adapted for veterinary medicine – and used for many types of solid cancer. In general, neoplasia staging systems include information about:

- where the tumour is located in the body

- the cell types

- the size of the tumour

- whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes

- whether the cancer has spread to a different part of the body

- tumour grade – how abnormal the cancer cells look, and the likelihood of the tumour growing and spreading

The TNM classification is a common and scientifically valid reference, and the principle of determining the extent of a tumour – in terms of local invasion, and nodal and distant metastasis – is important for the work-up of any cancer case.

Because TNM is a reproducible system, it allows comparison of cases both within the same institution and between different institutions. The close correlation between the clinical stage of the neoplasm, therapeutic options and prognosis is extremely important for the patient, its owner and the veterinarian.

The main limitation of the TNM system is this type of classification is applicable to most solid tumours – such as mammary, pulmonary and genitourinary – but not valid for haematopoietic malignancies such as lymphomas and leukaemia, and mast cell tumours. These are, in fact, staged according to the WHO system.

In the TNM system classification:

- T refers to the size and local invasiveness of the primitive/primary tumour.

- N refers to the number of nearby lymph nodes that have cancer.

- M refers to the presence of distant metastases – whether the cancer has spread from the primary tumour to other parts of the body.

T: clinical assessment of primary tumour

A thorough assessment of the primary tumour is important for surgical planning. The physical characteristics of the primary lesion may provide important information, such as the degree of malignancy, feasibility of surgical treatment and prognosis.

The size of the primary mass is, for example, important for mammary neoplasia, where masses smaller than 3cm in diameter tend to carry a better prognosis than larger ones.

For other neoplasia, T refers to infiltration and invasion of adjacent tissue (this is the case for bone, bladder, testicular and prostatic neoplasia). The degree of infiltration may reflect the degree of malignancy, and will affect both treatment and prognosis.

For other tumours, T is irrelevant, since, for prognostic purposes, the route of neoplastic diffusion is more important; this is the case with, for example, ovarian tumours.

Clinical assessment of the primary mass will give information on how well circumscribed the mass is, adhesion of the lesion to the deep planes, presence of ulceration of the overlying cutaneous layer and degree of mobility.

For superficial lesions, physical examination may be the only necessary test for clinical assessment of the primary tumour; whereas, for tumours in deeper locations (such as the head and neck, thorax and abdomen, and appendicular tumours), further investigations – such as radiography, ultrasonography, CT, MRI and endoscopy – are indicated.

Furthermore, procedures such as endoscopy allow collection of biopsy samples.

Staging of the size and local invasiveness of primary tumours is detailed in Table 1.

| Table 1. Size and local invasiveness of the primary tumour | |

|---|---|

| Description | Stage |

| No evidence of primary tumour | T0 |

| Increasing size and local extent of the primary tumour | T1, T2, T3, T4 |

| Carcinoma in situ | Tis |

| The primary tumour is unable to be assessed | Tx |

N: clinical assessment of local and sentinel lymph nodes

The sentinel lymph node (N) is the first lymph node draining and receiving lymphatic vessels from the anatomical region in which the tumour has developed.

The size, texture and mobility of the regional lymph nodes should be assessed on initial evaluation of the patient. To define N, it is important to establish whether the regional lymph nodes are fixed or mobile, their size and consistency, single or multiple involvement, and whether involvement is ipsilateral or contralateral (Figure 1).

Methods used in veterinary medicine to evaluate the sentinel lymph node are cytological evaluation, surgical excision (lymphadenectomy), scintigraphy, and peritumoural injection of contrast dye associated with radioactive tracer.

Regional lymph nodes with a neoplastic lesion should always be further investigated, by collection of fine needle aspiration and cytology. A negative cytology for lymph nodal neoplastic cells does not exclude the possibility of metastasis and lymphadenectomy, with histopathology representing the most secure method for evaluation of lymph nodes draining neoplastic masses.

Therefore, because cytology may give false negatives, the histopathological evaluation of the sentinel lymph node may be more reliable in reflecting the regional neoplastic extension, with obvious prognostic and therapeutic implications.

For this reason, the biopsy of the satellite lymph node is performed more often in human oncology, for the correct staging and identification of micrometastases not otherwise recognisable. In fact, micrometastases are impossible to identify by means of normal screening tests and believed to be responsible for late systemic neoplastic dissemination.

The N state has very important prognostic implications for many solid tumours – such as neoplasms of the head and neck, bladder and intestine – since it reflects the inability to effectively intervene on the primitive tumour.

Staging of the number of lymph nodes involved in the neoplastic process is detailed in Table 2.

| Table 2. Number of lymph nodes involved in the neoplastic process | |

|---|---|

| Description | Stage |

| No metastasis to the regional lymph nodes | N0 |

| Increasing involvement of regional lymph nodes | N1, N2, N3 |

| Regional lymph nodes are unable to be assessed | Nx |

M: clinical assessment of distant metastasis

Tumours can metastasise via the lymphatic route to local and regional lymph nodes, or via the haematogenous route to distant body organs. Some of them may spread by both lymphatic and haematogenous paths.

The lungs are the most common site for distant metastasis in small animals, but other sites – such as liver, spleen, kidneys, heart, brain, spinal cord, bones and skin – should be investigated.

Detection of metastases may be complicated because metastatic disease only becomes evident at a late stage when large enough to be detected by imaging techniques, such as radiographs or CT.

Staging of distant metastasis is detailed in Table 3. The presence of distant metastases defines whether the patient is operable and, in most patients, is associated with poor prognosis. Overall, the more voluminous and extended beyond the primitive organ of onset (to the lymph nodes or distant organs) the neoplastic lesion, the more advanced its stage is considered.

M can be clinically defined, but most often requires instrumental investigation.

| Table 3. Presence of distant metastasis | |

|---|---|

| Description | Stage |

| No distant metastasis | M0 |

| Distant metastasis is present | M1 |

| Distant metastasis is unable to be assessed | Mx |

Instrumental investigation for clinical staging

Instrumental investigations are often required to support the physical examination, and better define the clinical assessment of the size and local invasiveness of the primary tumour, the involvement of the regional lymph nodes and the presence of distant metastasis.

Such investigations include routine blood sampling, radiography, ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and, in some cases, endoscopy and bone marrow aspiration.

Routine blood sampling for haematology and biochemistry is always recommended because some tumours can be associated with paraneoplastic syndromes, such as hypoglycaemia or hypercalcaemia. Assessment of the bone marrow is useful in the diagnosis and staging of haematological malignancies, such as leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma, and in cases of systemic mastocytosis.

Clinical staging and diagnostic imaging

Collateral diagnostic investigations – such as radiography, ultrasound, CT and MRI – have noticeably improved the accuracy of the TNM clinical classification.

Radiography is still the most frequently used diagnostic imaging method for clinical staging of oncological patients. However, while it is low-cost and relatively available, its use for clinical assessment of the primary tumour – and local and regional lymph nodes – has been superseded by CT and MRI.

Radiography is useful for screening for enlargement of intrathoracic or intra-abdominal masses and lymph nodes, but can only detect gross changes in size. For staging routine thoracic (three views – two lateral and one dorsoventral) and abdominal (two views – lateral and dorsoventral) masses, radiographs are still recommended.

Thoracic radiography is a standard screening process for tumours of haematogenous metastatic route, as the lungs are often the first site for development of metastases (Figure 2). However, radiography is not always a very sensitive method. CT has been shown to be superior to radiography for detecting lung masses and pulmonary metastatic disease, particularly when thoracic radiographs are equivocal, or in cases of neoplasia with a high risk of pulmonary metastases.

CT is also more sensitive than radiography for detecting cervical or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. It provides good soft tissue definition of abdominal lymph nodes and can be used for the assessment of intra-abdominal lesions, as well as for surgical planning of the surgical dose (Figure 3).

Furthermore, CT is highly sensitive for fine bone details, as shown by the case in Figure 4 of a dog with a plasma cell tumour associated with multiple skeletal lesions (multiple myeloma).

Ultrasound examination has an important role in the evaluation of the site, size and extent of any tumour mass in the body. It is superior to radiography for assessment of abdominal organs and soft tissue lesions in the neck – and on limbs – because it allows identification of the extension of the lesion and its relationship with adjacent organs. Ultrasonography also allows guided fine needle aspirates of lymph nodes, liver and spleen to be collected for cytology, and measurement of the lymph nodes for initial staging and monitoring of the treatment response (Figure 5).

Because of the costs, length of time required to obtain images and need for general anaesthesia, MRI is, in most patients, not the method of choice for the clinical staging. However, it may be useful in selected patients for the assessment of the primary tumour involving the CNS, head and neck. It is usually not used for imaging neoplastic lesion of the thorax and abdomen, for which, as aforementioned, CT is preferable.