19 Apr 2021

Overview of mitral valve disease

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) – or simply “mitral valve disease” – is the most common cardiovascular disease and the most frequent cause of congestive heart failure (CHF) in dogs.

The prevalence (percentage of a population with a particular disease at a given point in time) of MMVD varies with age, and most geriatric dogs – especially those belonging to small breeds – will eventually develop this condition, although MMVD can also be diagnosed in larger breeds.

MMVD is a chronic degenerative disorder causing deformation of the entire mitral valve apparatus, including atrioventricular (AV) annulus, mitral valve leaflets, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles, and left atrial (LA) and left ventricular (LV) myocardium. These structural abnormalities lead to biomechanical dysfunction and mitral incompetence – also called mitral regurgitation, which is the most common manifestation of MMVD – and, with time, the associated volume overload can induce cardiac remodelling, characterised by LA and LV enlargement and, eventually, CHF.

The tricuspid valve is also commonly affected with an associated tricuspid regurgitation; therefore, some clinicians prefer to refer to this condition as AV valve degeneration.

This article will focus primarily on the diagnostic investigation of MMVD and management of associated clinical signs, with a particular emphasis on the treatment of stable and refractory CHF.

A presumptive diagnosis of myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is relatively straightforward, based on signalment (geriatric, small‑breed dog) and the presence of a newly developed systolic heart murmur with a point of maximum intensity over the left apex.

However, a definitive diagnosis requires a full echocardiographic examination with colour and spectral Doppler to confirm the presence of mitral regurgitation (MR).

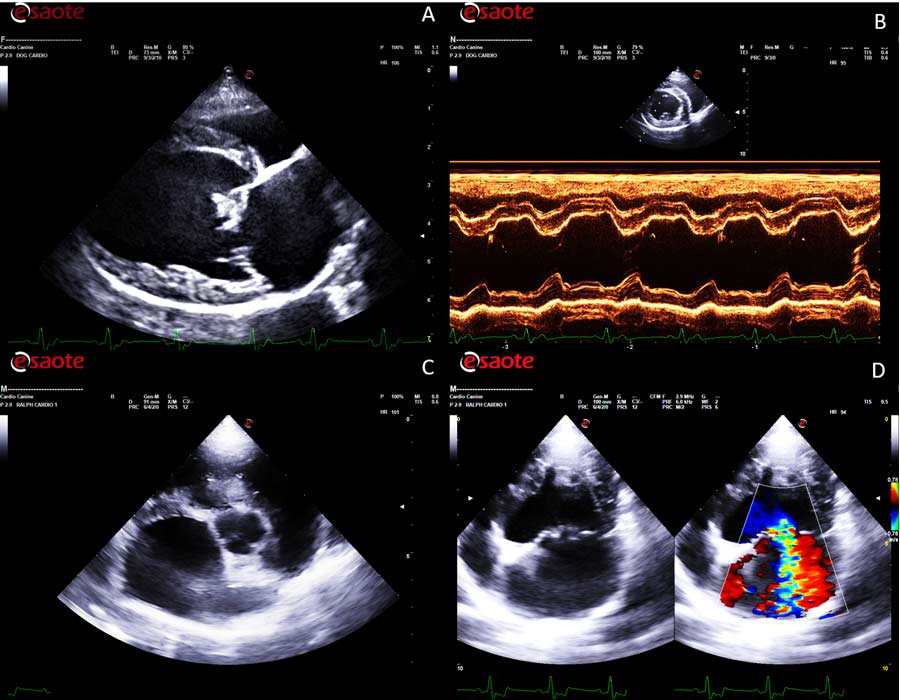

The main structural echocardiographic lesion associated with MMVD is characterised by thickening and distortion of the valvular leaflets and chordae tendineae, usually more pronounced at the level of the anterior mitral valve leaflet. The thickness and irregularity of the valvular leaflets tend to become more prominent during disease progression.

From a functional point of view, the main features of MMVD on B-mode (2D) echocardiography are the flattening of the mitral valve leaflets and their systolic prolapse, which is confirmed on echocardiography by observing one or both leaflets bending back towards the left atrium during systole.

Superimposition of colour flow Doppler (colour flow mapping [CFM]) at the level of the mitral valve will reveal the presence of systolic valvular regurgitation caused by the incomplete or inefficient apposition of the valvular leaflets.

Visualisation of valvular regurgitation on colour Doppler is characterised by the presence of a mosaic of colours caused by aliasing (an image artefact that occurs when the blood flow velocity exceeds the Nyquist limit) as blood rushes through the regurgitant orifice towards the left atrial lumen.

Many clinicians tend to activate the CFM in right parasternal four-chamber long axis view. However, the correct alignment for any Doppler assessment, including CFM, should be parallel to the blood flow; therefore, the best position to detect MR is the left parasternal four-chamber apical view.

This view will also allow a better visualisation of size and direction of the regurgitant flow, and a correct alignment of the spectral Doppler that can be used to estimate the pressure gradient between the left ventricle and the left atrium in systole.

Quantification of MR

While identification of MR on echocardiography is a relatively easy task, the quantification of MR is much more difficult.

Several techniques are available to estimate the regurgitant volume – for example, volumetric method, proximal isovelocity surface area, and vena contracta. However, no single method can be used to accurately calculate the severity of MR due to intrinsic technical limitations and poor repeatability, which tends to be particularly significant when different operators are involved in the echocardiographic study (high inter-operator variability).

For these reasons, semi‑quantitative methods – such as the colour jet Doppler area – represent an easier solution in a busy clinical setting.

This evaluation is based on the calculation of the maximal ratio of the regurgitant jet area signal to left atrial (LA) area (ARJ/LAA ratio) using CFM Doppler. Based on this method, MR is usually considered:

- trivial if the ARJ/LAA ratio is lower than 5%

- mild if it is between 5% and 20%

- moderate if it is between 20% and 50%

- severe if it is more than 50%

The major advantages of this method are the rapidity and simple acquisition, good repeatability and reproducibility in the awake dog. However, this technique can also be influenced by several factors, including systemic arterial blood pressure, LA pressure, spatial orientation of the jet, colour gain and colour aliasing settings (also named “scale” or “pulse repetition frequency”).

Furthermore, this method can lead to underestimation of severity in eccentric jets because they are prone to the Coandă effect, in which the jet impinges the left atrial wall, losing some jet energy and causing the jet to appear smaller.

Optical illusions should also be taken into consideration when comparing the size of the jet to the size of the left atrium since, in the presence of a large atrium, the regurgitant jet may appear smaller.

The severity of MR is also influenced by the driving pressure of the left ventricle. Hypertension, for example, may increase the degree of MR, while increased LA pressure would tend to decrease the amount of MR.

Quantification of left ventricular (LV) and LA dilation – also called signs of “cardiac remodelling” – can be very useful in the semi‑quantitative assessment of MR severity. Indeed, haemodynamically significant MR results in volume overload, which is characterised by LA and LV enlargement. This chamber enlargement is mainly caused by the MR, but it is exacerbated by water retention secondary to the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). The resulting increased preload and LV eccentric hypertrophy may, in turn, cause papillary muscle displacement, annular dilatation, and dysfunction and worsening of MR (mitral valve leaflets tethering).

The progression of MMVD is also associated with an increased sphericity of the LV, which is particularly visible in the advanced stage of the disease.

Recognising MMVD complications on echocardiography

The LA dimension has been recognised as one of the major prognostic indicators in several studies.

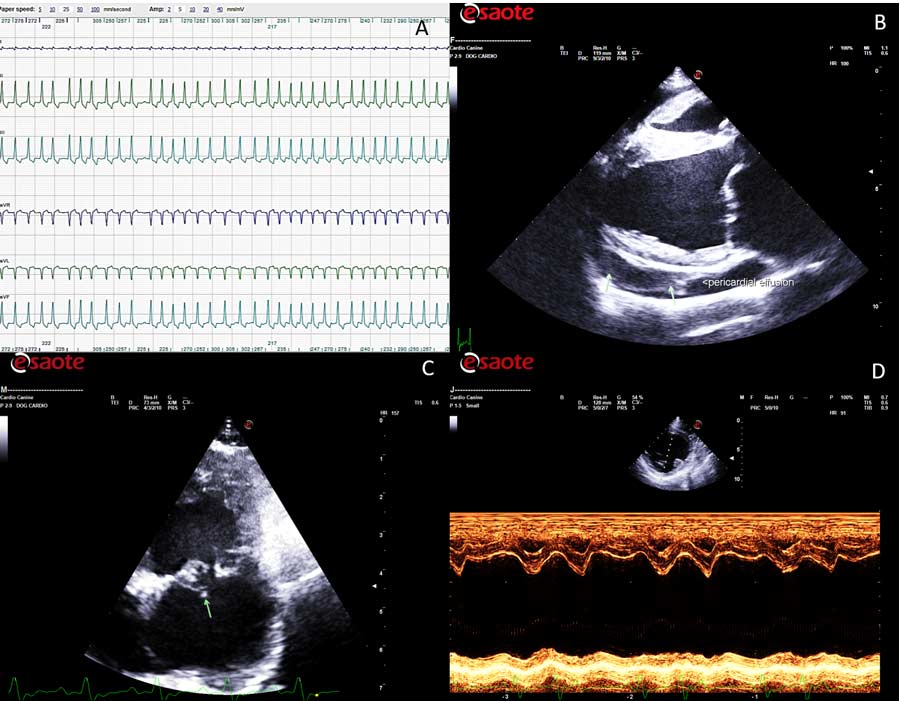

However, significant LA dilation can also predispose to atrial fibrillation (AF), which is associated with severe clinical complications such as haemodynamic disturbances, including loss of the atrial contribution to ventricular filling, increase in the mean diastolic atrial pressure, reduced interval for passive diastolic filling and worsening of the existing MR.

The relative contribution of these factors is likely to vary between patients and ventricular rate, which tends to be elevated in the majority of dogs with AF. Additionally, the sustained tachycardia and irregular rhythm associated with AF can predispose to further myocardial damage and systolic dysfunction (tachycardia‑induced cardiomyopathy or tachycardiomyopathy).

Furthermore, AF seems associated with an increased risk of sudden death in dogs with MMVD.

Severe left atrial dilation can also predispose to LA tear, which inevitably results in pericardial effusion with a visible blood clot in the pericardial space. The causes of spontaneous LA tear include increased LA pressure and lesions of the atrial endocardium due to severe MR (jet lesions). Atrial tear is also a differential diagnosis of sudden death in dogs with advanced MMVD.

Another relatively common complication that can be detected echocardiographically is the rupture of one or more chordae tendineae, which is often associated with a rapid deterioration of the regurgitant flow and further cardiac remodelling.

LV systolic myocardial dysfunction is another potential complication in MMVD, which can be recognised on echocardiography as hypokinesis of the LV free wall on M-mode study or speckle tracking of the LV.

Finally, the presence of significant pulmonary hypertension can represent another important problem in advanced MMVD. This diagnosis can be achieved with different direct and indirect methods, but the most commonly used is, once again, echocardiography, which can reveal the presence of a tricuspid regurgitation or pulmonic insufficiency with elevated jet velocity, enlargement of the main pulmonary artery, diastolic flattening of the interventricular septum, right ventricular and right atrial enlargement, dilation of the caudal vena cava, alteration of the morphology, and timing of the pulmonic flow.

Correct staging of MMVD

An accurate staging of MMVD allows a more precise prognostication of MMVD, as well as a useful guidance for successful therapy.

Staging is a clinically based measure of severity that uses objective clinical, radiographic and echocardiographic criteria to assess the stage of disease progression.

Several staging methods have been proposed in the past. However, nowadays, the most commonly used system refers to the classification of heart failure proposed in human cardiology in 2005, which was later adopted and modified by the “American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs”, published in 2009 and updated in 2019 (Keene et al, 2019).

Although it is important to acknowledge the fact dogs with MMVD may present with a variable degree of severity, even among individuals at the same stage of their disease, the correct diagnosis and staging facilitates a relatively immediate decision-making process.

A summary of staging guidelines according to the ACVIM consensus 2019 is reported in Table 1. Based on these guidelines, a point‑of‑care ultrasound performed by a competent ultrasonographer would be sufficient to assess the MMVD stage; however, the author always recommends a full echocardiographic examination – including colour and spectral Doppler studies – to detect any possible comorbidity or potential complications of the disease, as aforementioned.

| Table 1. Summary of the 2019 American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) consensus staging criteria and therapeutic recommendations (modified by the author) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage A | Stage B1 | Stage B2 | Stage C | Stage D | |

| Description | Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is not present, but the patient is at higher-than-average risk for developing the disease (for example, cavalier King Charles spaniels). | MMVD is present. No evidence of cardiac remodelling on echocardiography or thoracic radiographsa. | MMVD is present. Evidence of cardiac remodelling on echocardiography or thoracic radiographsa. | MMVD is present and severe enough to have caused at least one episode of congestive heart failure. | MMVD is present and severe enough to have caused refractory congestive heart failure. |

| Conservative management | None | None | • Sleeping respiratory rate monitoring • “Cardiac” dietb • Regular exercisec |

• Sleeping respiratory rate monitoring • “Cardiac” dietb • Regular gentle exercise |

• Sleeping respiratory rate monitoring • “Cardiac” dietb • Regular gentle exercise |

| Therapeutic management | None | None | • Pimobendan • Surgical interventiond • Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors? • Spironolactone? |

• Furosemide or torasemide • Pimobendan • Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors • Spironolactone • Surgical interventiond,? |

Same as stage C, but further interventions are often necessary to control clinical signs. |

| Rechecks | Annually by auscultation. | Annually by echocardiography (or radiography if echocardiography is unavailable). | Biannually by echocardiography (or radiography if echocardiography is unavailable). | Ideally every three to four months. | Whenever needed to stabilise the clinical condition. |

| a Criteria for inclusion in group B2 include murmur intensity greater than or equal to 3/6; left atrium:aorta ratio greater than or equal to 1.6 on echocardiography; left ventricular internal diameter in diastole, normalised for bodyweight, greater than or equal to 1.7 on echocardiography; and breed-adjusted radiographic vertebral heart score greater than 10.5. | |||||

| b Mild dietary sodium restriction, and provision of a highly palatable diet with adequate protein and calories for maintaining optimal body condition. | |||||

| c Regular gentle lead walks are believed to reduce the progression of muscle wasting and sarcopenia causing exercise intolerance and lethargy. | |||||

| d Mitral valve repair is possible, although financial affordability and availability of specialist centres in the area may represent limiting factors in some cases. | |||||

| ? Combined administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and spironolactone in stage B2 is not included in the ACVIM consensus; however, it has been demonstrated this intervention can significantly reduce the progression of cardiac remodelling in dogs with MMVD (stage B2). | |||||

Thoracic radiography should also be considered to evaluate the effect of haemodynamic changes on the pulmonary vasculature and the presence of an interstitial‑alveolar pattern suggestive of cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Furthermore, thoracic radiographs are invaluable for the diagnosis of airway or parenchymal disease that can cause respiratory signs.

Unfortunately, thoracic radiographs tend to be underused in veterinary cardiology due to the incorrect assumption that patients need to be heavily sedated or anaesthetised to obtain diagnostic images. Conversely, most dogs will tolerate a gentle conscious restraint on the radiographic table with accurately positioned sandbags, without sedation or anaesthesia.

Serum N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentration may provide additional information for MMVD staging when echocardiographic assessment is unfeasible for financial reasons. However, clinicians need to be aware of some limitations of diagnostic accuracy of this biomarker alone and the existence of breed-specific differences of normal NT-proBNP values. Nevertheless, a normal or near normal NT-proBNP concentration in a dog with dyspnoea or exercise intolerance strongly suggests a cardiac disease is not the cause of the clinical signs.

Diagnosis of heart failure and CHF

The most common clinical signs observed in small animals with heart failure (HF) – defined as a condition where the pumping ability of the heart (cardiac output) is no longer sufficient to satisfy the metabolic demand of the body tissues – include exercise intolerance, lethargy, inappetence, weight loss, respiratory changes and abdominal enlargement.

However, the most common clinical signs observed by owners of dogs and cats with HF are those associated with congestion (CHF), and are described as rapid or laboured breathing (tachypnoea and dyspnoea, respectively) or abdominal enlargement. Peripheral oedema observed in other species is not a common finding in dogs and cats with CHF.

Exercise intolerance and lethargy tend to appear before the onset of signs of congestion, but the transition from HF to CHF is not commonly observed by pet owners, especially in sedentary dogs or cats; therefore, the terms HF and CHF are often used interchangeably in small animal cardiology.

Tachypnoea/dyspnoea is primarily caused by the presence of pulmonary oedema and/or pleural effusion, although tachypnoea may also result from metabolic acidosis secondary to hypoperfusion of peripheral tissue or from ascites, since the pressure on the diaphragm induced by the fluid accumulated in the peritoneal space may interfere with the respiratory function and cause substantial discomfort.

Cough has been traditionally, but incorrectly, attributed to CHF for decades due to the presence of pulmonary oedema. However, the cough reflex is not present in the deeper respiratory tract since no coughing receptors are present at the level of respiratory bronchioles or alveolar wall. Furthermore, a large retrospective study involving 206 dogs with MMVD showed that, unlike tachypnoea/dyspnoea, cough is not consistently present in dogs with CHF and, in the same study, pulmonary oedema did not appear to increase the risk of coughing in those dogs.

Cardiomegaly – in particular LA enlargement – has also been indicated as a cause of coughing in dogs with MMVD, but, even in this case, the association between the cardiac size and the presence of cough is very weak, unless in the presence of an underlying airway disease.

Therefore, the most realistic explanation for the presence of cough in these patients is the presence of cardiac enlargement with a concomitant underlying respiratory disease.

CHF in a dog with MMVD is diagnosed based on typical signalment (mostly geriatric small or toy breeds), history (previous detection of a heart murmur and progressively increased breathing rate) and typical clinical findings (systolic heart murmur at the level of the left apex, tachycardia, tachypnoea and dyspnoea).

Although crackles are commonly reported in the veterinary literature as an indication of alveolar pulmonary oedema, the most likely mechanism of crackle generation is sudden airway closing during expiration and sudden airway reopening during inspiration, as it happens more commonly in pneumonia and interstitial parenchymal disease (for example, lung fibrosis in West Highland white terriers). Furthermore, rhonchi associated with bronchial disease are often mistakenly described as crackles by some clinicians.

Unfortunately, no specific diagnostic tests can reliably confirm or rule out the presence of CHF; therefore, such diagnosis is purely based on a careful and judicious clinical assessment. Nevertheless, thoracic radiographs can provide invaluable information to assist the clinician in this often challenging diagnosis based on the presence of cardiomegaly, venous congestion and the presence of an interstitial‑alveolar patter, mostly in the caudal lung fields, suggesting the presence of pulmonary oedema.

Point-of-care lung ultrasound can also be used as a first-line screening evaluation in respiratory-distressed or respiratory‑compromised dogs with MMVD by differentiating “wet lungs” (B-lines) from “dry lungs” (glide sign and A-lines).

Normally, in dogs and cats without respiratory disease, B-lines are infrequently detected, and when present, are found in low numbers at a single site. Conversely, the presence of significant pulmonary oedema can produce multiple B-lines, which, in association with a confirmed LA enlargement, can support a diagnosis of CHF.

However, it should be borne in mind that B-lines are not pathognomonic for the presence of pulmonary oedema and they can be observed in primary respiratory diseases, such as interstitial pneumonia and diffuse parenchymal lung disease.

Measurement of cardiac biomarkers can certainly add useful clinical information, although these tests cannot reliably distinguish between a compensated patient and one in CHF.

Interventions to delay the onset of CHF

Prolonging the asymptomatic stage of a dog affected by MMVD is certainly one of the major objectives of veterinary cardiology. Initially, this was attempted by introducing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) before the onset of CHF, but, unfortunately, two large controlled studies failed to prove any real benefit of this intervention.

However, in 2016, the results of the EPIC Study demonstrated the administration of pimobendan in asymptomatic dogs with evidence of cardiac remodelling (characterised by normalised left ventricular internal diameter in diastole greater than or equal to 1.7, LA to aortic ratio greater than or equal to 1.6 on echocardiography, and vertebral heart sum greater than 10.5; Table 1) can significantly postpone the onset of CHF (Boswood et al, 2016).

Therefore, following this important discovery, pimobendan has been added in the updated ACVIM guidelines as a recommended intervention in dogs with stage B2 MMVD.

In 2020, another controlled study – the DELAY Study – demonstrated that the administration of combined benazepril and spironolactone can reduce the progression of cardiac remodelling in dogs with MMVD stage B2, although this medication failed to significantly extend the asymptomatic phase in that dog population (Borgarelli et al, 2020).

Finally, compelling evidence is growing that a moderate salt restriction in the diet can mildly reduce cardiac remodelling; this information should also be taken into account for therapeutic plans.

Interventions to control the clinical signs of CHF

Diuretics

Diuretics are effective in providing symptomatic relief and remain the first line treatment, particularly in the presence of pulmonary oedema.

In general, diuretics should be introduced at a high dose to solve the signs of congestion rapidly and effectively. After resolution of clinical and radiographic signs of congestion, the dose can be decreased according to the clinical response (minimal dose that can control the clinical signs). However, dangers exist in either undertreating or overtreating patients with diuretics, and regular review is always necessary.

Loop diuretics

Loop diuretics – such as furosemide and torasemide – have a powerful diuretic action, increasing the excretion of sodium and water via their action on the ascending limb of the loop of Henle. They have a rapid onset of action.

Patients receiving high‑dose diuretics should be monitored for renal and electrolyte abnormalities. Hypokalaemia, which may precipitate arrhythmias, should be avoided, and potassium supplementation, or concomitant treatment with a potassium sparing agent, should generally be used unless contraindicated.

Thiazide diuretics

Thiazide diuretics – such as chlorothiazide – act on the cortical diluting segment of the nephron, inhibiting the reabsorption of sodium and chloride. They are very safe diuretics with a low potential for toxicity problems in non‑azotaemic patients and can be used where a rapid diuresis is not necessary.

Potassium sparing diuretics

Amiloride acts on the distal nephron, while spironolactone is a competitive aldosterone inhibitor. However, their overall diuretic effect is very mild.

Counteracting the RAAS activation

ACEi

ACEi have shown beneficial effects on mortality and quality of life in prospective clinical trials, and are indicated in all stages of symptomatic heart failure, as recommended in the ACVIM guidelines, although a recent publication (the VALVE Trial) suggested that addition of the (ACEi) ramipril to pimobendan and furosemide did not have any beneficial effect on survival time in dogs with CHF secondary to MMVD (Wess et al, 2020).

Spironolactone

The early addition of spironolactone to standard therapy should also be considered in all dogs with CHF, as indicated by the ACVIM guidelines. Indeed, ACEi can reduce aldosterone production by inhibiting the conversion of angiotensin I into angiotensin II. However, they cannot inhibit “local” aldosterone production (chymase activity in heart and blood vessels).

Furthermore, the use of spironolactone may reduce myocardial remodelling, as observed in human patients.

The clinical benefits of adding spironolactone to ACEi therapy has also been demonstrated in dogs, where the addition of this drug improved patients’ quality of life and reduced the risk of mortality by 65% (Bernay et al, 2010).

Spironolactone can be administered alone or in tablets containing combined spironolactone and benazepril.

Sleeping respiratory rate

Most dogs with stable medically controlled CHF have a sleeping respiratory rate (SRR) below 30 breaths per minute and relatively small day-to-day changes in SRR in the home environment.

Therefore, SRR measured at home by the pet’s owner can reliably be used to monitor the therapeutic response and clinical stability of dogs with MMVD and CHF.

- Some drugs in this article are used under the cascade.