9 Dec 2022

Preventing calf scour – the pillars of calf management

Image: © Adobe Stock / etonastenka

In Ireland, dairy farms predominantly operate spring block calving systems, which means efficient production of replacement heifers is the focus from birth.

At the author’s practice, the clients are almost all spring calving, pasture-based herds. This means tremendous pressure is on the calf management systems, as the calving period is only 10 to 12 weeks long.

Very little room for error exists in calf rearing if all your heifer calves are born in a two-month period and are required to make it to calving at 22 to 24 months.

A few fundamental pillars exist in good calf management; these include:

- colostrum

- hygiene

- housing

- nutrition

If a breakdown occurs in any of these, it will result in breakdowns of disease including calf scour and pneumonia, as well as poor growth rates.

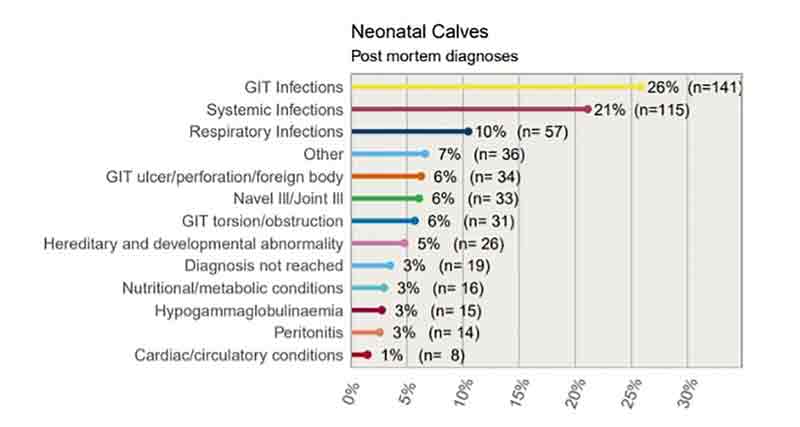

Figure 1, from the All Island Disease survey 20201, shows the leading cause of death in calves under 30 days is calf scour, followed by systemic infections and pneumonia.

It is important that, through management, we, as practitioners, work with our clients to try to avoid these illnesses, so improving their performance, and ultimately, sustainability.

Colostrum management

As we know, calves are born without any immunity to infectious agents; they are entirely dependent on colostrum as a source of antibodies.

The concept of passive transfer is something farmers are becoming more aware of, but a way is still to go on that journey, so it’s important to keep pushing that discussion.

The author’s practice has made inroads in this area by breaking it down into clear messages:

- Calves can absorb antibodies through their intestines immediately after birth, but this ability declines rapidly in the first 24 hours of life.

- Failure of passive transfer leaves calves more susceptible to scour, respiratory infections, systemic infections and navel ill1.

We are all aware of the 3-2-1 rule, highlighting the importance of giving 3L of colostrum in the first two hours of life, from the first milking of the cow, but no harm comes in reiterating this, reminding clients and checking it is being carried out on farm.

It is important not to make assumptions about what is being practised at farm level, as this can lead to nasty surprises.

Even when it does take place, issues can arise, such as poor colostrum quality or inadequate colostrum storage, or the collection of colostrum may not be hygienic enough.

The author’s main rules for effective colostrum management are:

- Give at least 3L of colostrum in the first two hours of life (10% to 12% of bodyweight).

- All colostrum is assessed for quality and calves are fed colostrum that measures at 22% or higher on a refractometer. This is the equivalent of 50g/L of IgG2. Colostrum quality is easily assessed on farm using a refractometer and all farm staff should be trained to use it.

- Colostrum should be harvested and fed in a hygienic manner, as even modest numbers of bacteria in colostrum can affect the efficiency of absorption3.

Vaccination of cows prior to calving can help boost the levels of antibodies to specific pathogens present in colostrum, enhancing the protection calves receive.

To reduce calf scour is significant, as is the feeding of transition milk4, to fully avail of the antibodies against the scour-causing pathogens present in the colostrum of vaccinated cows. Vaccination can help prevent scours such as rotavirus, coronavirus and Escherichia coli5.

Colostrum also contains oligosaccharides that are thought to help prevent pathogen adhesion to the intestinal epithelium, but their effects are not yet fully understood4.

As vets, we can troubleshoot/quality control by taking blood samples from calves 24 hours to seven days old and measure serum total protein. A reading of 5.5 or greater indicates good passive transfer6.

Hygiene

Hygiene is fundamental to disease prevention in calves. Colostrum should be harvested using clean equipment, stored in clean containers, and fed using clean feeding equipment. If you can ever observe colostrum being taken and prepared for storage, take the opportunity as it won’t be presented often. Reinforce the importance of biosecurity in calf housing.

Implementing the following controls will reduce the risk of introduction and spread of disease:

- The calf house should not have open access; disinfection should be available at the point of entry, and clean boots and overalls should be available. How often do we see systems that don’t quite fit the bill, but say nothing?

- Calf buyers should not enter the calf shed and calves that are being sold on farm should be taken out of the shed for the buyer to see, rather than have the buyer enter the calf shed. Not a huge change to what clients could already be doing, but something that can make a huge difference.

- It is not good practice to wear the same apron or overalls that have been worn for milking and are heavily contaminated with faecal material – obvious, perhaps, but not uncommon to see.

- Any sick calves must be isolated immediately; the healthy calves should be looked after first before sick calves are attended to.

- Calves’ navels should be disinfected at birth using a chlorhexidine-based product rather than iodine, and calves moved to a clean, dry pen that is cleaned out and disinfected after each calf7.

Housing

Calves have a lower critical temperature (LCT) of 15°C and calves under three weeks are the most vulnerable to change. This means during February and March – when most calves are born in Ireland – the environmental temperature is typically well below the LCT.

Under these conditions, calves need to use more energy to keep themselves warm, and this can lead to reduced growth rates and immunosuppression. Therefore, it is up to us to ensure calves are kept warm enough and provided with increased nutrition to ensure energy requirements are met.

Calves should be fed an extra 50g of milk replacer or 330ml of milk for every 50°C drop in temperature. Moisture and draughts increase the LCT8.

Below is a quick reference checklist:

- Calves need clean dry beds. Pens should be washed and disinfected after each calf. However, moisture in the calf shed should be kept to a minimum as it provides an ideal environment for pathogens to multiply.

- Bed deeply with straw. Calves need to be able to nest. We can assess this through nesting scores. The straw should be up over the knees of calves when lying.

- Calves should wear jackets to keep them warm in colder temperatures. It is important to thoroughly wash and disinfect calf jackets between calves. Jackets are not a substitute for poor management and are of little use if calves are lying on wet straw.

- Kneeling test. If you kneel on the calf’s bed, it should be dry. If your knees get wet, then a pathogen-friendly environment is being generated and calves will be cold.

- Ensure the calf shed is draught free. Crouch down to the level of the calves and look for movement in the straw.

- Ventilation. Calves do not produce enough heat to generate a stack effect for ventilation, so positive pressure ventilation may be needed. Ventilation can be easily assessed on farm by using smoke bombs, this is a useful exercise to do with the farmer.

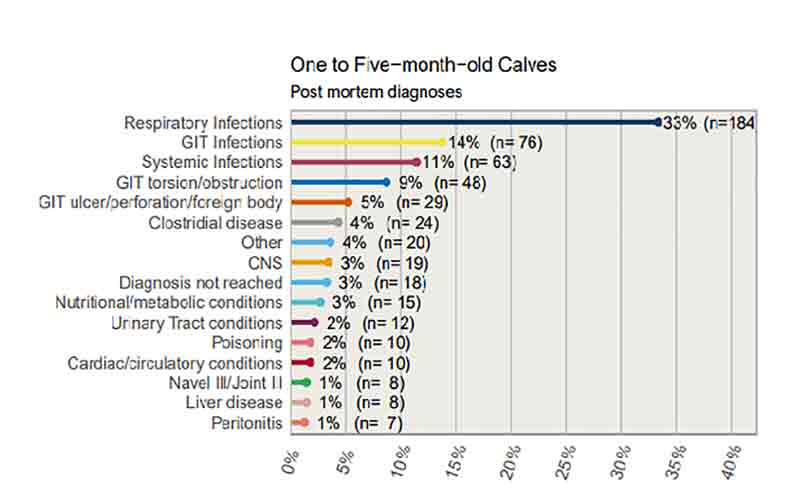

Poor housing can lead to respiratory infections in calves; pneumonia is the leading cause of death in calves from one month to five months old9.

It is important calves are vaccinated against pneumonia viruses once they reach the appropriate age. A single case of pneumonia can cost as much as €136 (£117.37) per calf up front. This is in addition to the consequential loss of dairy heifers not making it to first lactation. As many as 14% of dairy heifer calves do not make it to first lactation, and pneumonia is an important cause of these losses10 (Figure 2).

Nutrition

The fourth and final component of calf management is feeding, and our knowledge and understanding around this is constantly evolving.

A number of different approaches to milk feeding exist. Understanding the pros and cons of each will allow you to support your clients, and recognise and resolve problems when they occur.

Some basics are:

- Calves must be fed a minimum of 15% of their bodyweight daily. For a 40kg calf, 15% of bodyweight is 6L, which equates to 3L twice daily initially, but as the calf grows, it requires more milk. This equates to 750g of milk replacer split across two feeds. This is necessary to ensure a daily live weight gain of 0.8kg. Early weight gain is important to ensure calves are 30% of their mature bodyweight at six months old and 60% of mature bodyweight at breeding11.

- Always weigh out the milk powder, as significant variation can exist between batches. This variation can lead to underfeeding or overfeeding; in turn, this causes significant stress on the calves and can result in disease outbreaks.

- Do not feed non-saleable whole milk to calves, as it can increase the risk of disease transmission and antibiotic resistance4.

- Calf meal should also be introduced and a source of fibre, such as straw, should also be provided. This is essential to promote rumen development. Calves should be eating 1kg daily for three or more consecutive days prior to weaning4.

- Calves need access to a clean water source from birth. Far too often, the author sees calves with no access to water4.