22 Jul 2019

Preventive strategies in calf respiratory disease

Figure 1. Use of calf jackets can help reduce cold stress in neonatal calves.

Calf rearing can be one of the most challenging, yet rewarding, jobs on farm. These young animals require a lot of care and attention to detail, but with their ability to grow rapidly and mature at a relatively early age, farmers can reap the rewards of good calf management in a matter of months.

Any calfhood diseases threaten the ability to rear calves at a reasonable cost due to the incursion of high treatment costs, compounded with reduced production parameters and death.

Calf respiratory disease (CRD), more commonly referred to as pneumonia, has one of the highest disease prevalences, being a principal cause of morbidity and mortality within the pre-weaning demographic (van der Fels-Klerx et al, 2002) and costing farmers around £60 million per year (National Animal Disease Information Service, 2007).

Short-term effects of reduced growth rates of up to 66g (Virtala et al, 1996) are mirrored with long-term consequences, such as a three-month increase in age at first calving (Warnick et al, 1994).

Despite a reasonable understanding of the pathogens involved, and the development of numerous treatment and prevention strategies, pneumonia still poses a great risk to the health and welfare of calves. This is partly due to its multifactorial aetiology, and the inter-related risk factors that cause diagnostic challenges and therapeutic inconsistencies (Karle et al, 2018), and partly because we still ignore many of the management areas that result in increased calf susceptibility.

Management to minimise respiratory disease

Optimising the calf’s own immune system to reduce its susceptibility to development of respiratory disease requires maintenance of a healthy body, as well as minimising environmental pressures.

Calf factors that predispose to disease are very well documented in the literature, and include adequate transfer of maternal antibodies via colostrum, sufficient supply of energy and protein nutrition through plentiful milk feeding, proper transition on to solid feeds, and minimising the occurrence of stressful events, such as transportation. We will not labour on these aspects in this article, other than to highlight the immune system requires a lot of energy to function correctly, so investing money into optimising energy intakes and maximising growth rates will have a positive effect on health parameters.

Environmental temperature is something that is difficult to control, but account must be taken of its effects on calf health.

Traditionally, pneumonia is thought of as a winter disease, but its prevalence is heavily influenced by changes in weather, with large differences in day and night temperatures, and high humidity levels all occurring at the changing of the seasons.

The use of calf jackets is one way to try to combat cold stress, especially when temperatures consistently fall below 15°C for calves less than three weeks of age (Figure 1). The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) offers sound advice on the use of calf jackets, such as ensuring the presence of a min/max thermometer in the calf housing – to aid in deciding the timing of jackets being used – and ensuring the jackets are made of a breathable, water-resistant and machine-washable material.

Heat stress is also known to increase the rate of calf pneumonia (Louie et al, 2018), with individual calf hutches suffering from souring temperatures when positioned in direct sunlight with minimal air flow.

Humidity is another factor that is difficult to manage, with recommendations for less than 70% humidity in sheds often unattainable when the lowest average daily UK humidity is recorded as 69% (World Data Center for Meteorology, 2019).

If the air we push into sheds already has a high water content, the only option is to keep refreshing this air to prevent stagnation and buildup of aerosols. Due to changeable and unpredictable weather in the UK, we must ensure calf housing is optimised to try to combat these uncontrollable weather variables.

Housing options for calves

Many housing options are available for calves, each with its own set of challenges. The main driver for housing selection is often what is already available on the farm, but investment into either new buildings, or major modifications to existing structures, is always an investment into future success.

The three key areas housing must excel in are the ability to remain hygienic, the provision of adequate ventilation and temperature control, and the ease of use by the people employed to do the calf rearing.

This last point can be overlooked when farm decisions are made by people not involved in the day-to-day chores, but if workers are forced out into cold and exposed locations to care for calves, it is highly likely the attention to detail required to do the job well will fall dramatically during periods of cold and wet weather. This is mostly applicable to the use of individual calf hutches, where daily bedding-up and individual animal feeding leads to long periods spent outside.

The ability to maintain high levels of hygiene in calf housing requires the ability to regularly and thoroughly remove organic matter and disinfect.

Gold standard cleaning would also involve complete emptying and resting of housing for at least a week, but, again, this may be challenging when room is limited. If a conventional shed is used for housing, it is important machinery is able to enter it to allow thorough removal of bedding and manure. Portable housing options allow for complete removal of the structure to a fresh area of ground, but cleaning of faecal material from the walls of the house should not be forgotten.

Although not directly linked to respiratory disease, use of disinfectants that are effective against coccidia should be considered as calves suffering from diarrhoea become immunocompromised and are, therefore, more susceptible to acquiring pneumonia as well.

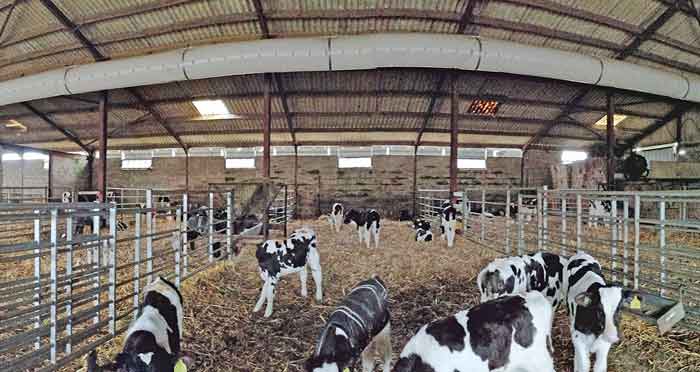

Conventional buildings and polytunnel designs can work well, as long as ventilation and light levels are considered. Whether using individual or group pens, a stocking density of 3.3m2 of bedded area per calf is the recommended minimum requirement (Nordlund and Halbach, 2019), with increasing space helping to reduce buildup of faecal contamination and reducing calf pen bacterial counts (Lago et al, 2006). It also allows the calves to exercise and play, which is an important aspect of behavioural development.

Further things to reduce CRD include the use of solid barriers between calf pens, which will reduce the prevalence of respiratory disease by lowering exchange of airborne pathogens and preventing nose-to-nose contact (Lago et al, 2006; Figures 2 to 4).

The ability of calves to nest in bedding is also important as it helps them to reduce heat loss and avoid draughts by trapping a layer of warm air around themselves (Webster, 1984).

In addition to conventional buildings and plastic polytunnel designs, three main types of portable calf housing are available – individual calf hutches, group calf hutches/igloos and calf pods.

Individual calf hutches have proven popular due to the perceived reduction in disease prevalence that is achieved by reducing the transmission of pathogens by creating an individual microclimate for each animal. However, problems with poor animal socialisation and behavioural deficits, along with reduced solid feed intakes compared to pair or group-housed calves, means their use is becoming controversial (Costa et al, 2016).

If weaning is carried out based on weight gain, this reduction in growth rates in individual hutches can result in longer periods spent on milk feeding, thereby increasing rearing costs and decreasing farm efficiency. This, along with increased management time required to individually bed and feed each pen, and problems around temperature control (too cold in winter, too hot in summer), has led to decreasing popularity and a blanket ban from some milk suppliers.

Group hutches or igloos are a great step towards investing in a sustainable calf housing system. They offer the advantages of grouping calves for ease of care and feeding, while still being portable to aid in cleaning. A more recent development is a calf pod designed as a flat-packed package that can house 10 calves, with a deep litter flooring and is easily transportable by hitching it up to a tractor three-point linkage.

Air quality and ventilation strategies

The respiratory tract has several physiological adaptions to aid in pathogen trapping and removal, such as nostril hairs providing a physical barrier to large particles and a mucous lining that contains several antimicrobial factors to trap particulates. In addition, non-specific immune cells, such as bronchoalveolar macrophages and neutrophils have phagocytic function. However, these innate immunological protective mechanisms are ineffective against dust particles less than 5µm, which are able to reach the lung parenchyma and alveoli. These dust particles are themselves irritant, able to act as fomites for microbes, and can absorb and transfer gases, such as ammonia, into the lungs (Lampman, 1982).

Ammonia is a toxic irritant to cells. In the respiratory tract, it causes increased neutrophil presence in the nasal mucosa (Urbain et al, 1994), as well as demonstrating a synergism with Pasteurella multicida bacteria in other mammalian species, whereby the bacteria are able to proliferate in the upper respiratory tract at levels of 10ppm (Hamilton et al, 1996).

Ammonia measurements in reasonably well-ventilated calf housing show levels of around 5ppm, but levels can rise to more than 20ppm in areas of poor ventilation and also when muck is being disturbed in pens, such as when cleaning out (Hillman et al, 1992; Figure 5). This can be significant in sheds housing multiple pens of calves that are cleaned out at different intervals.

Many calf buildings try to use natural ventilation through open eaves or side walls to allow the prevailing wind to force air into the shed, but this runs the risk of draughts and, therefore, cold stress affecting the calves (Lago et al, 2006).

The recommendation is to have four complete air changes per hour within an animal shed (Bates and Anderson, 1979), which is surprisingly low given on aircrafts up to 15 changes per hour are recommended to reduce the risk of aerosol disease spread between people.

Mechanical positive pressure ventilation is the most readily available way of improving pre-existing buildings, more commonly referred to as tube fans (Figure 6). These tube fans distribute air evenly into a barn, which then require openings in the eaves and ridge to allow the air to exit.

Tube fans must be designed and bought specifically for a shed, as the size of the tube and of the holes will need to be calculated using fluid mechanics principles to ensure enough air is pushed into the shed without creating draughts (Nordlund and Halbach, 2019). The purchase and installation of tube fans will cost £1,000 to £2,000, with minimal daily running costs and maintenance required.

Calves are the most vulnerable population of animals in a cattle enterprise, requiring dedicated staff and facilities, as well as good protocols to ensure their health and future productivity is not compromised.

Respiratory disease is a major risk to these aims, but the optimisation of calf housing through good hygiene, ventilation adjustments and consideration of temperature can help reduce environmental risk factors.