9 Apr 2018

Pros and cons of adopting TIVA techniques for field anaesthesia

Alison Bennell discusses the advantages and disadvantages of this method in regards to safety and cost.

Figure 2. A well-secured, short-stay IV catheter with a three-way tap for quick administration of drugs.

Field anaesthesia based on total IV anaesthetic techniques has many advantages. The benefits for the horse include safety and less cardiorespiratory depression than inhalational anaesthesia, benefits to the client include reduced cost and avoiding the need for hospitalisation for their horse, and benefits to vets include minimal specialist equipment being required and the speed of completing the surgery without having to wait for owners to arrange transporting their horse to a clinic setting.

Other disadvantages include not being able to extend the anaesthetic period significantly, and confidence with protocols and monitoring horses under injectable anaesthetic techniques requires familiarity.

Field anaesthesia based on total IV anaesthetic (TIVA) techniques may seem daunting to the inexperienced equine practitioner, but once familiarity with field protocols is gained, it is a pleasure to undertake.

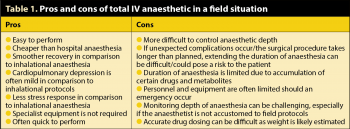

This part of the article aims to detail the pros and cons of field anaesthesia, and discuss decision making as to whether it is suitable for certain procedures. Part two will detail drugs and total IV protocols.

It is well known theatre-based equine anaesthesia has a significant inherent risk, with large multicentre studies showing a mortality rate of approximately 1% in healthy horses1. Studies into mortality of horses under TIVA show, for comparable length of anaesthetics, it is associated with less risk of death compared to theatre-based inhalational procedures.

For many reasons, field anaesthesia may be considered for short procedures. The pros and cons are listed in Table 1.

Field versus hospital anaesthesia

For short procedures, field anaesthesia has many advantages over hospital anaesthesia. It is safer due to the reduced stress response, and the drugs used produce significantly less cardiorespiratory depression than inhalational protocols. TIVA, in a field setting, also negates potential risks of transportation-related injury and hospitalisation-related risks, such as nosocomial infection.

Total anaesthetic time, including surgery and preparation, must be realistically estimated, as extending field anaesthesia with injectable agents to produce more than an hour of anaesthetic time will lead to an accumulation of drugs and active metabolites, which can be problematic. Also, if surgical complications occur, or if surgery takes longer than estimated, no back up exists of converting to inhalational anaesthesia. For these reasons, a reasonable time buffer should be included when planning surgery in a field situation.

Planning

Before undertaking anaesthesia in the field environment, planning is vital and will help ensure things run smoothly. Important points to consider include the type of surgery to be undertaken, personnel available, premises and individual horse factors, including temperament and handling.

Cost of field anaesthesia

Equine anaesthesia can add significant expense to a surgical procedure. Generally, field anaesthesia requires less specialised equipment, less experienced personnel and fewer drugs, which means, overall, it will be significantly cheaper to the client than an inhalational anaesthetic of similar duration.

The overhead costs associated with hospital inhalational anaesthesia are considerable in terms of buildings and equipment set-up. With the increasing costs of transporting horses, the ease of performing simple surgeries at an owner’s premises can also add to the appeal of avoiding hospitalisation.

Suitable premises

In field anaesthesia utopia, a flat, grassy paddock with post and rail fencing or an indoor school with a chipped rubber surface would be available, although this situation is often hard to come by (Figure 1). Other suitable locations include a stable well-bedded with straw with no wall fittings that could cause injury to personnel or the patient, a paddock with no obstacles lurking in the undergrowth, or a sand school where you can pay particular attention to protecting eyes and airways from the sand.

Beware of rubber matting in stables, which can become incredibly slippery when wet – especially after the application of routinely used surgical scrub solutions. Other horses or animals in the field can cause complications as they are often inquisitive and can distract the handler or veterinary surgeon from concentrating on their patient and they can interfere with induction or recovery when space is needed. The elements can also provide complications as trying to keep a surgical site aseptic in the wind and rain can prove challenging.

Specialist equipment

The equipment needed for field anaesthesia is debatable, with some anaesthetists advocating the use of specialised equipment and others adopting a more minimal approach.

Aseptic placement of a well-secured IV catheter is of paramount importance in all animals before field anaesthesia is undertaken (Figure 2). This ensures patent venous access is maintained at all times, should it be needed either for a bolus of anaesthetic agent in response to movement that may be sudden and violent, or emergency drugs should an allergic reaction or anaphylaxis be suspected or a sudden adverse event occur. By placing the catheter up the vein, it means, should the three-way tap or extension be dislodged, it is easy to notice and will rule out the possibility of an air embolism.

In the author’s opinion, the placement of an endotracheal tube and supplying supplemental oxygen via a demand valve or flowmeter is often not practical in field conditions, and this equipment is not routinely carried by the majority of ambulatory equine vets. While it is gold standard practice to be able to maintain a patent airway and provide oxygen, routine supplementation of oxygen with a flowmeter is unlikely to significantly increase the fraction of inspired oxygen and, should a true emergency situation occur, it is unlikely sufficient personnel or drug supplies will be available to attempt to perform successful cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation.

If an endotracheal tube is placed, it is prudent to thoroughly flush the mouth prior to anaesthesia to reduce the chance of contamination of the trachea and lower airways.

Monitoring equipment in the field is often limited to vets (or a delegated competent person, such as a nurse or veterinary student), their senses and a stethoscope. If one person is to perform the field anaesthetic and surgery, such as castration, valuable time can be taken up by constantly checking the patient rather than concentrating on the surgery and minimising the anaesthetic time.

Easily transportable equipment, such as a pulse oximeter, can be useful, but is often unreliable – for example, due to vasoconstriction caused by α2 agonists – and precious time can be taken up worrying about readings when your response to these readings may be also limited.

Personnel

Anaesthesia of horses carries risk to the personnel involved and by allowing owners to be present, thorough explanation and instructions are required to ensure they are unlikely to come to harm.

When performing planned injectable anaesthesia in the field, it is useful to have either another vet, RVN or a competent undergraduate veterinary student as a second pair of hands, as it is challenging performing surgery while maintaining and monitoring anaesthesia. A competent owner can be very helpful, but caution should be exercised if the owner is the only help available; if difficulties do arise, either surgically or with the anaesthesia, an experienced pair of hands and some moral support is invaluable.

Weight estimation

Accurate weight estimation can be difficult in some patients and several methods can be used to help improve accuracy when weigh scales are not available. These include weigh tapes, which often underestimate, and formulae exist to help provide greater accuracy2:

With most adult horses, the limited drugs we have available for IV field anaesthesia have relatively large safety margins, so it is difficult to significantly overdose a large animal. Underdosing is problematic, as inductions can be uncoordinated, cause excitation or violent reactions or fail to induce anaesthesia at all; therefore, it is considered safer to overestimate weight, which will be discussed in the later article on TIVA protocols.

Procedures suitable to be performed under field anaesthesia

Whether it is appropriate to perform a field anaesthetic will depend on many factors. Safety is a primary concern of personnel and the patient; however, circumstances arise where the situation is less than ideal, such as when an owner does not want the expense of referral or a horse that cannot be loaded and basic surgery is required.

Emergency situations also lead to less than ideal circumstances with regards to premises and the stressed horse to be anaesthetised. Ideally, surgical procedures lasting less than 45 to 50 minutes are considered suitable as this allows a buffer for things to take a bit longer than planned.

Records, consent and insurance

It is wise to gain informed consent prior to any procedure. This does not mean an exhaustive written form needs to be signed; consent can be verbal, although in some cases, a signed form may be useful. A written record should be kept by vets regarding verbal discussions and consent, as is standard for ambulatory work, as they can be very useful should any complaints arise.

Decisions by the owner must be informed, so the risks of the anaesthetic and surgery must be explained.

It is also worth noting unlicensed drugs are commonly used in equine anaesthesia and this can be included in a consent form.

Anaesthetic records applicable to hospital settings are not suitable for use in the field. Field anaesthesia should be prompt and time spent filling out an extensive record form can often be better spent getting on with the job at hand. A basic record will help document drug use (and help with accurate billing), and recording the anaesthetic time and when the horse has recovered can also be useful.

When to leave

From a legal standpoint, vets should stay with the horse until it is fully recovered from the effects of the anaesthetic agents. Even if under pressure because of more calls to do, staying with the horse until it is standing and ambulatory, as well as ensuring the owner is clear on postoperative care, are minimum expected standards of practice.

Latest news