7 May 2021

Rise in canine transmissible venereal tumour cases

Image © TheOtherKev / Pixabay

Dear editor,

We are writing because we have seen an increase in the number of cases of canine transmissible venereal tumour (CTVT) in samples submitted to our laboratory, predominantly in dogs imported from Romania, and wish to alert colleagues to this fact.

CTVT is a horizontally transmitted, infectious, usually benign tumour of dogs typically transmitted by coitus – but also by licking, sniffing and biting of tumour-affected areas – leading to direct implantation of tumour cells.

It was first recognised in 1876, but believed to have been present for 4,000 to 8,000 years, first emerging in Asia before spreading worldwide1. It typically affects young, entire, sexually active, free-roaming dogs, and is most common in tropical and subtropical regions, probably due to higher numbers of stray dogs in countries with lower income economies2.

CTVT was once common in the UK, but declined and was eventually eradicated during the 20th century as an unintended consequence of The Dogs Act 1871 and other subsequent dog control laws, which effectively eliminated the free-roaming dog population2. Sporadic cases are seen in dogs that have travelled to endemic areas.

Histiocytic lineage

CTVT cells are generally accepted as being of histiocytic lineage and can overcome host major histocompatibility barriers via complex immunomodulatory interactions.

Tumours typically arise within two to six months of mating, but can arise many years after neutering – suggesting either the latent period can be much longer than previously thought, or that neutering does not entirely protect dogs2.

A progressive phase, characterised by three to six months of tumour growth, is followed by the stationary phase, which can last for months to years. This is then followed by spontaneous regression, unless the host is immunosuppressed, in poor condition or geriatric. Spontaneous regression rarely occurs if the tumour has been present for more than nine months3.

The tumours initially present as small, hyperaemic papules on the external genitalia or within the vagina, which progress to friable, nodular, ulcerated, cauliflower-like masses up to 15cm in diameter, which may exude serosanguinous fluid and tend to bleed (Figure 1). Intermittent bleeding from the genitalia may be the first clinical sign noted. Tumours may predispose to urinary tract infections, but rarely interfere with micturition. Anaemia may result from prolonged blood loss.

Tumours may also affect extragenital locations such as the nose, lips, oropharynx and eyes, with clinical signs depending on location (for example, sneezing, epistaxis, epiphora, halitosis and exophthalmos). Occasionally, the tumours may be implanted into the skin rather than into the mucous membrane4.

The majority of the tumours are benign, with metastasis reported to occur in less than 15% of cases (this may be an under-representation as many cases are not fully staged)5. There may be direct spread to the cervix and uterus in females, or metastasis to the inguinal and ileac lymph nodes.

Rarely, if a dog is immunocompromised, metastasis may involve other organs such as the skin, eyes, tonsils, liver, spleen, brain, peritoneum and bone marrow6.

Cytology

The cytology cases we have seen through the laboratory, submitted by clinicians unused to seeing CTVTs, include suspected ovarian remnant syndrome, suspected urinary tract infection, suspected coagulopathy (all due to bleeding from the genitalia and/or haematuria) and suspected mammary neoplasia (due to involvement of inguinal lymph nodes).

Tumours within the vagina may require vaginoscopy for detection, while penile tumours are commonly around the base of the shaft, requiring retraction of the prepuce for exposure, so tumours can escape initial clinical examinations and may not be apparent when a dog is being prepared for export.

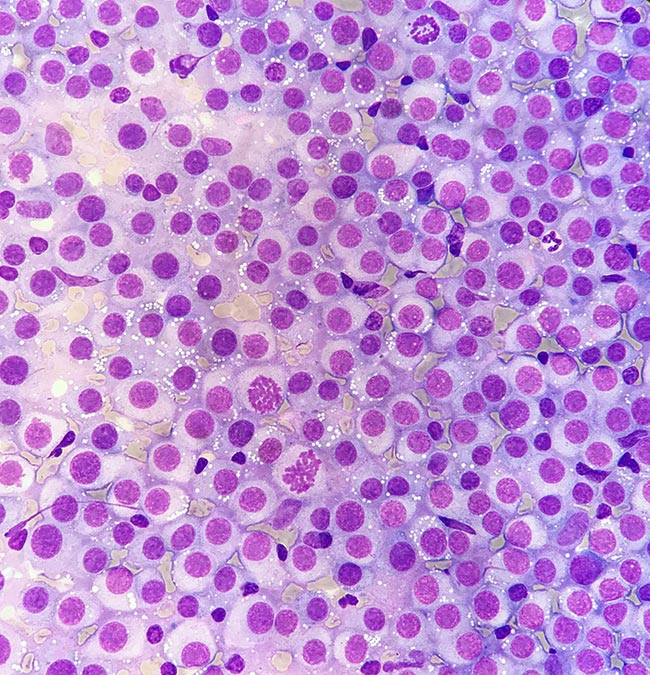

Once the mass or masses have been identified, diagnosis is usually straightforward based on location, travel history, macroscopic appearance and characteristic cytologic features (Figure 2).

Histology is often not necessary, but immunohistochemistry can be employed to distinguish CTVTs from other round cell tumours (histiocytoma, lymphoma, plasmacytoma, poorly granulated mast cell tumour and amelanotic melanoma) if cytology or histology is ambiguous. A PCR test that can be performed on paraffin-embedded tissue has recently become commercially available at Michigan State University.

Treatment

CTVTs are very susceptible to chemotherapy, with 90% to 95% of cases achieving complete and lasting remission with single agent vincristine employed at 0.5mg/m2 to 0.7mg/m2 or 0.025mg/kg IV once weekly for three to six treatments. In refractory cases, doxorubicin (25mg/m2 to 30mg/m2 IV every 21 days for three treatments) may be used5. CTVTs also respond well to radiotherapy.

Surgery is not advisable due to high tumour recurrence rate and risk of iatrogenic implantation of tumour cells to other sites in the same dog during surgery.

Imported dogs

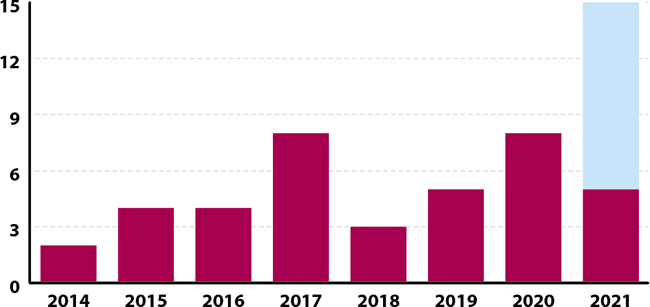

Of the 39 confirmed cases submitted either to Axiom Veterinary Laboratories or its sister laboratory, Finn Pathologists, where travel history was available, 35 have been in dogs imported from Romania, with a single case each in dogs originating from Hungary, Serbia, Egypt and China. Figure 3 represents confirmed cases per year (data for both laboratories combined), since instigation of our current laboratory information management system.

The over-representation of Romanian dogs no doubt reflects the recent surge in dogs imported from this country, and the high prevalence of CTVT in Romania. A survey performed in 2014 reported an estimated incidence of CTVTs in Romanian dogs as 5% to 10%.

Other European countries with a relatively high estimated prevalence of CTVTs are Macedonia (estimated 5% to 10%) and Ukraine (estimated 3% to 5%), while occasional cases occur in Belarus and Bulgaria (estimated 0.5% to 1% prevalence), and France, Italy, Greece and Hungary (estimated lower than 0.5% prevalence). Not all countries participated in the survey2.

CTVT is unlikely to become established as an endemic disease in the UK due to stringent dog control laws and widespread neutering. However, an imported dog harbouring CTVT poses a potential risk to non-travelled dogs – even if neutered – due to the possible transmission of tumour cells during non-sexual contact. The veterinarian may, therefore, act as the first line of defence against a cluster of cases occurring in a non-endemic country.

There has been recent widespread publicity within the veterinary community about cases of Brucella canis imported from Romania. We write to increase awareness that, along with other better recognised infectious conditions, CTVT may be harboured by dogs imported from Romania and other European countries, and to highlight that lesions can be missed on initial clinical examination.

Yours faithfully,

NIKI SKELDON, MA, VetMB, DipECVCP, FRCPath, MRCVS,

KATE SHERRY, BVetMed, DACVP, MRCVS,

Axiom Veterinary Laboratories,

The Manor House, Brunel Road, Newton Abbot,

Devon TQ12 4PB.

References

- Baez-Ortega A et al (2019). Somatic evolution and global expansion of an ancient transmissible cancer lineage, Science 365(6,452): eaau9923.

- Strakova A and Murchison EP (2014). The changing global distribution and prevalence of canine transmissible venereal tumour, BMC Vet Res 10: 168.

- Ganguly B et al (2016). Canine transmissible venereal tumour: a review, Vet Comp Oncol 14(1): 1-12.

- Agney DW and MacLachlan NJ (2017). Tumors of the genital systems. In Meuten DJ (ed), Tumors in Domestic Animals (5th edn), Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken: 718-721.

- Woods P (2019). Miscellaneous tumors. In Vail DM, Thamm DH and Liptak JM (eds), Withrow and MacEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology (6th edn), Elsevier, St Louis: 783.

- Mello Martins MI et al (2005). The canine transmissible venereal tumor: etiology, pathology, diagnosis and treatment. In Concannon PW, England G, Verstegen III J and Linde Forsberg C (eds), Recent Advances in Small Animal Reproduction, International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca.