30 Oct 2017

Senior pets: latest advice to give cat and dog owners

Cecilia Villaverde discusses how to define whether a small animal is considered old and ways of dealing with dietary needs.

Figure 1. Approach to nutritional assessment in ageing dogs and cats.

Dogs and cats are living to increasingly greater ages. According to the Pet Food Manufacturers’ Association, the dog and cat population in the UK in 2017 is estimated to be 8.5 million and 8 million, respectively.

Ageing can be defined as the progressive physiological and metabolic changes that occur in the body after maturity, which leads to a decrease in organ function3. Signs of ageing include whitening of the hair, decline in coat condition, failing senses, behavioural changes4, and other less apparent changes in body composition, immune function, brain morphology and digestive physiology. Neurological changes associated with age, such as canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome, have been described in dogs and cats5, potentially due to oxidative damage.

It is important to address the specific dietary needs of senior pets. However, no straightforward general nutritional recommendation exists for this population because not all pets age equally and a lack of published data is available about nutritional requirements for this life stage. At this time, neither the scientific authority6, nor the European Pet Food Industry Association, give specific nutrient recommendations for ageing pets.

Defining a senior pet

No standard definition exists for senior pets. Ageing is a continuum and individuals vary greatly as to their ageing process, so any age classification should be taken as a guide. Moreover, organs age at different speeds within the same individual.

The American Animal Hospital Association’s Senior Care Guidelines Task Force7 proposed pets be considered senior when they are in the final 25% of their predicted life span, which is estimated from their species and breed.

Some authors have proposed cut-off ages, but those are highly subjective. For example, in cats, the American Association of Feline Practitioners8 classifies ageing cats as mature (7 to 10 years old), senior (11 to 14 years old) and geriatric (more than 15 years old). For dogs, breed size affects lifespan, with smaller breeds living longer than larger breeds. Proposed cut-off ages for dogs to be considered geriatric are 11.5, 10, 9, and 7.5 for toy, medium, large and giant breeds, respectively9.

Ideally, each pet should receive an individualised ageing assessment10, where “milestones”, such as joint disease and muscle atrophy, are recorded as they happen. This would be a better measure of ageing rather than a cut-off age. For this reason, all pets, independently of age, should receive a nutritional evaluation at every visit11, assessing the animal, diet and feeding method, and instituting changes as necessary as the patient gets old (Figure 1).

Energy needs

Studies in Labrador retrievers have shown longevity is increased and incidence of OA decreased in those dogs fed less calories and kept lean – with a body condition score (BCS) of four out of nine – compared to controls12; therefore, ensuring an adequate energy intake to promote a lean BCS is important in senior dogs.

A tendency exists for older dogs to have a lower energy requirement than young adults6, likely due to loss of lean body mass (more metabolically active than fat) and decreased activity, and this could promote higher BCS than desired.

In cats, no evidence exists of significant changes in energy requirements by age13; however, mature and senior cats (7 to 12 years old) tend to have problems with obesity, which might signal lower energy requirements. Interestingly, geriatric cats (more than 12 years old) have an increased prevalence of being underweight associated with loss of fat and fat-free mass14, which could result from an increase in energy needs of very old cats, although it can also reflect decreased energy digestibility and decreased food intake, too.

Overall, senior dogs and cats can have issues with both obesity (due to decreased energy requirements) and underweight issues. Besides increased energy needs, senior pets can be underweight due to physiological or pathological lean body mass loss (Figure 2) or have decreased energy intake due to loss of olfactory and taste capabilities, or periodontal disease. Moreover, some common diseases in senior pets – such as neoplasia, chronic kidney disease and OA – can decrease food intake (due to inappetence or difficulty accessing food), and/or increase energy requirements and promote weight loss.

Nutrient needs

Protein

No evidence suggests protein needs are decreased in senior pets compared to young adults. On the other hand, no conclusive evidence shows those requirements are higher, although a few studies14,15 have found a higher percentage of older cats show decreased protein digestibility and muscle atrophy, which could result in a higher protein requirement.

It has been suggested older dogs have higher protein turnover and, thus, slightly higher requirements than young adults9, but this has not been quantified. In any case, lower protein diets are not routinely recommended for senior pets unless the animals have a disease where protein moderation is part of the nutritional management.

It is extremely important to note protein intake depends on overall food intake and is closely linked to energy intake. Patients that do not meet their energy requirement (due to inappetence, inability to access food or oral disease, for example) will not meet their protein needs either, since both dietary and body protein will be catabolised to obtain energy.

Fibre

Fibre is included in many senior diets to decrease energy density and help prevent or treat overweight conditions. Moreover, some types of fibre (prebiotic fibre) could potentially help promote a desirable gut microbiota, which can be affected by ageing, but no data at this time suggests using dietary fibre in this manner has any impact on quality of life or longevity.

Minerals

No evidence supports different mineral needs (such as sodium or phosphorus) in senior versus adult dogs and cats, despite some claims that senior pets need fewer of those nutrients to account for decreased kidney function. In dogs and cats with chronic kidney disease, the use of veterinary diets with controlled amounts of these minerals is indicated, but restriction before the disease is diagnosed does not have any proven benefit.

Other

Some diets marketed for older pets include a variety of nutrients that claim to have a positive effect, such as antioxidants and fatty acids (omega-3 and medium chain). Some data supports the use of a specific antioxidant mixture16 to help manage the signs associated with canine cognitive dysfunction together with behavioural modification, theoretically by reducing oxidative stress.

Other studies17 found a positive impact of a medium-chain triglyceride-enriched diet in canine cognitive dysfunction, and it is hypothesised the ketone bodies formed from this type of fat provide an alternative energy source to glucose for the brain.

How to choose a diet plan for a senior dog and cat

Nutritional evaluation

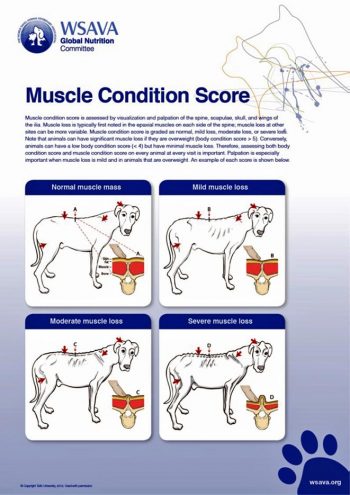

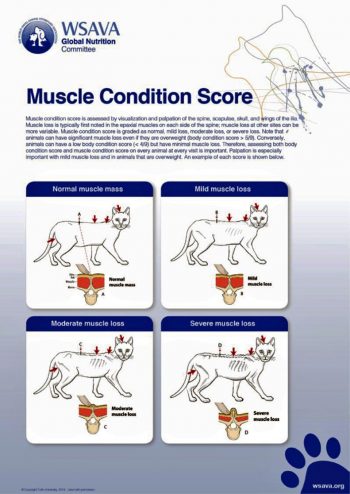

A detailed nutritional evaluation of the pet, the diet and the feeding method should be performed at every visit11. This includes a physical exam with assessment of body fat stores using BCS and muscle condition score (Figure 3 and 4). The latter is a subjective measure of muscle atrophy, which can be found in senior pets due to physiological reasons (sarcopenia of ageing) or be pathological (cachexia associated with disease).

A detailed history (including diet history) is also part of the nutritional evaluation, to identify diseases that are amenable to nutritional management, such as obesity, OA and chronic kidney disease.

Senior pets can have mobility issues, so the evaluation should identify any potential obstacles the pet may face when accessing food, such as location of food bowl, oral disease and neck pain.

Amount to feed

Energy requirements of senior dogs are estimated to be 95kcal to 105kcal per kg0.75 per day6. In cats, adults need 100kcal per kg0.67. Variability of these estimates is extremely high (+/− 50%), therefore, these formulas are only a starting point. The same variability applies to label recommendations. Bodyweight and BCS of senior pets should be carefully monitored every two to four weeks initially, and used to increase or decrease the daily calorie allowance.

Diet choice

As mentioned previously, no legal definition exists for what a senior diet is for dogs and cats. Therefore, the senior diets in the market will vary depending on the philosophy/approach of the manufacturer. One study18 compared reported nutrient values (protein, fat, energy, fibre, sodium and phosphorus) in several senior diets for dogs in the US and found those values had a very wide range. This means recommending a senior diet is not a useful recommendation for pet owners, and those should be considered as a sub-section of the maintenance adult diets and assessed individually to fit the purpose of the diet change.

It is important to choose the diet regarding the findings of the nutritional evaluation. Old pets that are doing well, maintaining their bodyweight and with a normal physical exam do not require a diet change. However, older pets with conditions such as obesity, OA and chronic kidney disease might benefit from a diet change, such as veterinary therapeutic diets formulated for those diseases. Some senior diets from reputable companies with claims to help manage canine dysfunction syndrome are adequate choices in dogs with this problem. Also, dental disease is common in elderly patients, and canned foods can be easier to prehend and masticate than dry food.

In dogs and cats with evidence of muscle mass loss, either physiological or pathological, protein intake should be assessed. All efforts should be made to ensure they eat all their energy requirements (for example, they maintain a stable bodyweight) before considering a switch to a higher energy diet. Some kitten and puppy diets can be used in cats and dogs that require a higher protein intake, and some brands even formulate senior diets, especially feline, to be higher in energy and protein content for these particular cases.

Feeding management

The feeding method should be adapted to the nutritional evaluation and the owners’ lifestyle. Overweight pets will benefit from portion-controlled, multiple-times-a-day feeding. On the other hand, ad libitum feeding can help with thin, picky eaters. Using environmental enrichment at meals is indicated in overweight patients and in those with cognitive dysfunction – use of toy food dispensers, for example.

Follow-up

A detailed nutritional evaluation at each visit, including bodyweight, BCS, muscle mass condition and diet history, will help you decide if the plan is adequate or needs adjusting. It is important to counsel owners on how to perform some of these assessments, since things can change rapidly in elderly pets.