20 Feb 2024

Strangles: its epidemiology and circulating strains in UK

An illustration of strangles taken from A treatise on the horse and his diseases (1884). Image: Public Domain.

Strangles is a bacterial disease reported in veterinary literature as early as the 13th and 17th centuries1,2, and to this day remains a substantial risk to horses.

The causative agent of the disease, Streptococcus equi (S equi), was identified in 18883 and is a host-restricted pathogen affecting horses, donkeys and mules4. Despite early historical references to the disease, a large-scale genetic analysis of internationally collated S equi strains found that the ancestor of contemporary strains dated back to the 19th century5, providing evidence of a global population replacement.

The timing of the shared ancestry corresponds to a period when horses were commonly used in warfare, enabling the mixing of horse populations and their pathogens on an international scale.

S equi is highly infectious, with high morbidity rates6 and can spread across premises rapidly if an infected horse is not identified and isolated on presentation of clinical signs, or if biosecurity measures are insufficient. Strangles can affect any horse on any yard, and the financial implications of a strangles outbreak on commercial premises, such as riding schools or competition yards, can be substantial7.

Strangles infections typically last around four to six weeks, with clinical signs progressing over the course of infection, including nasal discharge, pyrexia, lymphadenopathy and abscessation of the lymph nodes, which can be more aggressive in naive horses8. Strangles surveillance in the UK, based on laboratory detection of S equi between 2015 and 2019, showed that nasal discharge and pyrexia were the most frequently observed clinical signs at the time of sampling9. This indicates the need for equine veterinary surgeons to consider S equi in their testing when horses present with non-specific signs of respiratory infection.

Current epidemiological picture: strangles in the UK

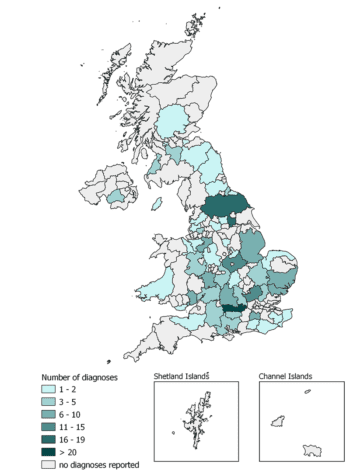

An online resource from the Surveillance of Equine Strangles network (SES) is available for equine practitioners and horse and yard owners to explore, allowing them to assess the broad geographical distribution of recent laboratory diagnoses of strangles in the UK. The resource also summarises any clinical signs reported by attending veterinary surgeons at the time of sampling (tinyurl.com/EIDSstrangleshub). Users can explore data collated by SES from 2015 up to the most recently reported diagnoses.

Using this tool to examine strangles diagnoses during 2023, a total of 210 strangles cases were reported to SES from samples submitted by 91 equine veterinary practices across the UK. Diagnoses spanned all four countries of the UK, including the Isle of Man (Figure 1).

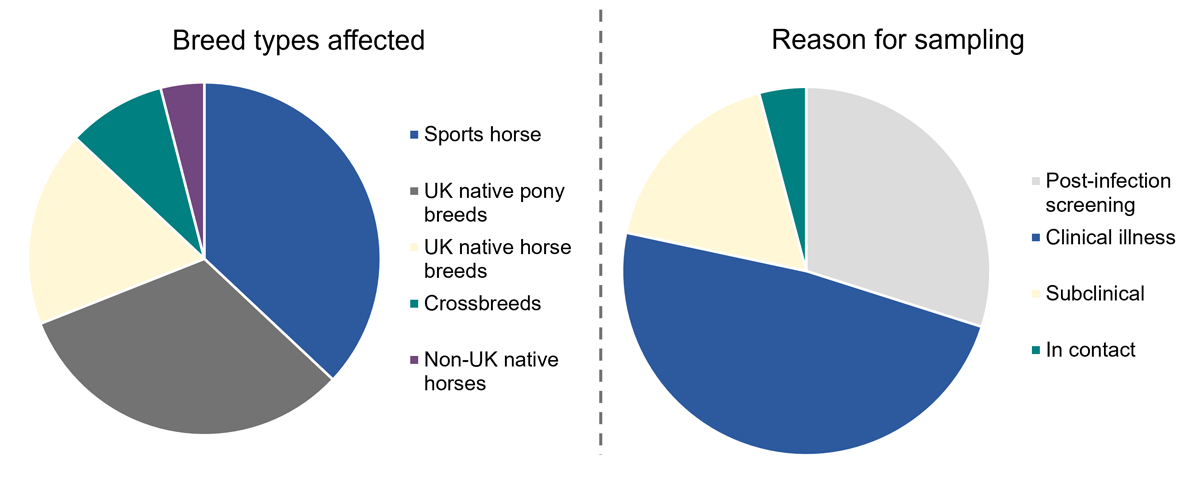

Where reported (n= 111), 69% of affected horses were either sports horses or UK native pony breeds, and 18% were UK native horse breeds (Figure 2), which likely reflects their popularity within the UK equine population rather than an inherent increased susceptibility to strangles. Where reason for sampling was reported (n= 129), nearly half of horses (47%) displayed clinical illness, 29% were sampled as part of post-infection screening, 4% sampled after being in contact with an infected horses and 17% were identified with subclinical infection.

Challenges in containment: navigating the persistence of strangles

Historically, S equi strains were thought to be identical10. However, as technologies improved, researchers began analysing different S equi isolates to further understand the pathogen. In 2009, whole genome sequencing (WGS) of an S equi strain isolated from a horse with strangles in 1990 was completed4. It was found that S equi shares 97% of its DNA with S zooepidemicus and key gene loss and gain events were identified that led S equi to become a host-restricted pathogen.

Furthermore, these gene loss and gain events form the basis on which S equi continues to adapt and spread to new horses. These adaptations can be monitored to understand which genes are important to S equi and how they may be beneficial or detrimental to the transmission of specific strains. Many of the genes identified as having been important for the evolution of S equi continue to undergo adaptation, including those linked to virulence and evasion of the host’s immune system5.

These adaptations have led to hundreds of different S equi strains circulating around the UK11, and globally12. Interestingly, although many strains of S equi have been recovered, they remain very closely related, to the point where examination of a large collection of S equi strains recovered from 19 countries across a 60-year period identified just six broad groups of strains that were predominantly linked to global geographical regions12. Within these clusters, it was also revealed international movement of horses was supporting the spread of once geographically restricted strains to new areas of the world.

Work undertaken as part of a PhD project at the RVC, kindly funded by The Horse Trust, examined S equi strains from horses in the UK between 2016 and 2022. Strains were recovered from horses sampled by equine practitioners as part of clinical investigations, post-infection clearance protocols, as part of pre and post-movement screening measures, or after a positive strangles serology test.

More than 500 samples contributed to the analysis, with results suggesting a much quicker change in the predominant group of S equi strains circulating among horses in the UK than previously expected. The observed speed of changes in circulating strains suggests that acute infection, or recently convalesced subclinical horses returning to normal activity on the assumption that they are clear of infection, may be larger drivers of strangles transmission and endemicity in the UK than previously thought.

Lack of biosecurity was recently ranked as the highest priority welfare issue affecting the UK equine population13, and the reactive nature of horse and yard owners to implement biosecurity once an outbreak has begun has been reported14-16. This, coupled with suboptimal post-strangles outbreak screening protocols and the frequent movement of horses across the UK for competition, breeding, health care, sales and more, is thought to be a large driver of strangles endemicity.

Future outlook: strategies for strangles management

The best strangles management starts with preventive work. Horse owners can implement simple measures daily to help reduce the risk of a strangles outbreak occurring on their premises. These measures include regular hand washing or sanitisation, preferably between handling horses on the same premises and most definitely after contact with horses from different equestrian premises.

The value of daily temperature checking must be stressed and horse owners/carers should be implementing this in their routines – ideally at the same time each day. Knowing their horse’s temperature range will then help owners/carers spot a change in their average temperature and move into action before other more obvious clinical signs may show.

Veterinary surgeons have been classed as a reliable source of information by horse owners16, and what owners may find beneficial is to understand how they can “use what they’ve got” on their premises as part of a preparedness plan if they find themselves dealing with an infectious horse. For example, guidance from their veterinary surgeon on how they can set up a quarantine space specific to their yard (or even an area of a field if no stabling is available) will go a long way to help owners feel ready to tackle an outbreak.

Should horse owners find themselves in the position of dealing with a strangles outbreak on their premises, steps can be taken to help monitor horses and reduce the possibility of infection passing between other horses on the premises.

A “traffic light” management system has been recommended for strangles outbreaks where all horses on the premises should be assessed and placed into a colour coded management system17.

Horses placed into the red group are presumed infected and showing one or more clinical signs consistent with strangles. Horses in the amber group have had direct or indirect contact with an infected horse and are at risk of S equi exposure, but are not yet showing clinical signs. Horses in the green group have no known direct or indirect contact with amber or red horses and are not showing any clinical signs of infection.

Rectal temperatures of amber and green horses should be taken twice daily and any horses with a raised temperature (around 38.5 °C) must be moved into the red group immediately. Each group has its own colour-coded yard equipment throughout quarantine.

Feed and water buckets should be regularly disinfected and sanitising stations and foot dips should be implemented. If possible, dedicated staff caring for horses in each group would prevent the transmission of S equi between groups. If not possible then staff should work moving from horses in the green group, to amber horses and then red group.

Communication is key throughout a strangles outbreak, and it is important to establish if more than one veterinary practice is involved in caring for affected horses within an outbreak. If so, aligned outbreak management advice should be given by all practices to avoid confusion between clients. The importance of post-outbreak screening must continue to be emphasised by veterinary surgeons when discussing outbreak management.

The design of a clear plan from start to finish may also help keep up compliance with management measures if a clear end goal is “in sight” for all affected. Providing a range of screening options to affected owners and premises and creating a plan that works for all at the start of the outbreak may be preferable to enforcing a “gold-standard” approach, which to some may seem too expensive or vigorous and lead to non-compliance.

With a view to the future, a novel strangles vaccine (Strangvac) has come on to the veterinary market in Europe, and its availability represents a potentially exciting and novel additional tool for the prevention and control of this highly significant and still prevalent equine infectious disease. The new vaccine, being based on specifically selected fusion proteins rather than killed or modified live bacteria, can be used alongside state-of-the-art diagnostic agent detection and serological assays, which are widely used for confirming natural disease.

Use of a vaccine that allows ready differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA) unlocks the possibility of not only getting ahead of the threat of strangles, but also offering significant improvements in the control of outbreaks, as the spread of infection can be accurately monitored using agent and antibody detection diagnostics, while strategic use of vaccination across the population will raise levels of resistance to disease.

Conclusion

Surveillance of laboratory diagnoses of strangles across the UK continues to highlight the endemicity of strangles across all four nations. The main drivers of the continued spread and transmission of S equi are thought to be inadequate application of biosecurity measures by horse and yard owners, the continuous movement of horses within and between UK regions (and internationally) and poor preparedness should an outbreak arise.

Moving forward, collaboration and communication between equine veterinary surgeons and horse/yard owners and wider adoption of enhanced biosecurity measures including the new vaccination, should prove invaluable to helping reduce the spread of strangles across the UK.

References

- Ruffus J (1251). De Medicina Equorum.

- Solleysel J (1664). Le parfait maréchal.

- Schütz J (1888). The streptococcus of strangles, J Comp Pathol 1(3): 191-208.

- Holden MTG et al (2009). Genomic evidence for the evolution of Streptococcus equi: host restriction, increased virulence, and genetic exchange with human pathogens, PLoS Pathog 5(3): e1000346.

- Harris SR et al (2015). Genome specialization and decay of the strangles pathogen, Streptococcus equi, is driven by persistent infection, Genome Res 25(9): 1,360-1,371.

- Timoney JF (1993). Strangles, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 9(2): 365-374.

- Waller AS (2014). New perspectives for the diagnosis, control, treatment, and prevention of strangles in horses, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 30(3): 591–607.

- Boyle AG et al (2018). Streptococcus equi infections in horses: guidelines for treatment, control, and prevention of strangles – revised consensus statement, J Vet Int Med 32(2): 633-647.

- McGlennon A et al (2021). Surveillance of strangles in UK horses between 2015 and 2019 based on laboratory detection of Streptococcus equi, Vet Rec 189(12): 1-9.

- Galán JE and Timoney JF (1988). Immunologic and genetic comparison of Streptococcus equi isolates from the United States and Europe, J Clin Microbiol 26(6): 1,142-1,146.

- McGlennon A et al (2020). Utilising genomics to identify potential Streptococcus equi (S equi) contact networks in the UK, Equine Vet J 52(S54): 15.

- Mitchell C et al (2021). Globetrotting strangles: the unbridled national and international transmission of Streptococcus equi between horses, Microb Genom 7(3): mgen000528.

- Rioja-Lang FC et al (2020). Determining a welfare prioritization for horses using a Delphi method, Animals 10(4): 647.

- Rosanowski SM, Cogger N and Rogers CW (2013). An investigation of the movement patterns and biosecurity practices on Thoroughbred and Standardbred stud farms in New Zealand, Prev Vet Med 108(2-3): 178-187.

- Spence KL et al (2022). Challenges to exotic disease preparedness in Great Britain: the frontline veterinarian’s perspective, Equine Vet J 54(3): 563-573.

- Crew C, Brennan M and Ireland J (2023). Implementation of biosecurity on equestrian premises: a narrative overview, Vet J 292: 105950.

- Waller AS (2013). Strangles: taking steps towards eradication, Vet Microbiol 167(1-2): 50-60.