18 Apr 2016

Treating feline lymphoma

Shasta Lynch outlines the more common types of lymphoma in cats and explains recommended treatment options.

Figure 4. A cat receiving IV chemotherapy.

Feline lymphoma is most commonly treated with chemotherapy – and the type of chemotherapy protocol administered is largely dependent on the grade and location of the tumour.

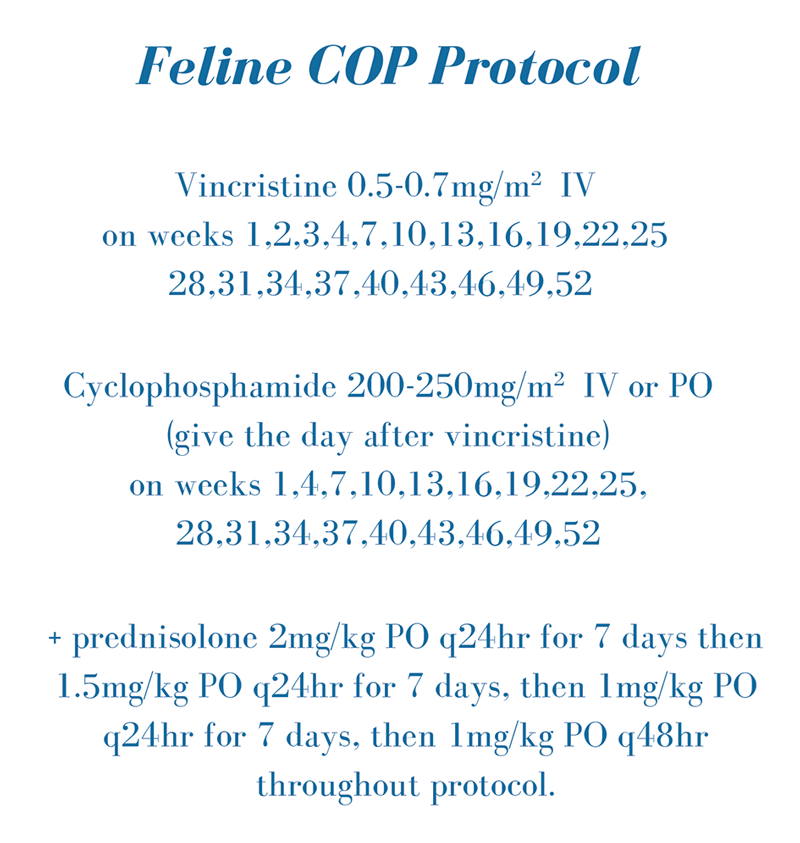

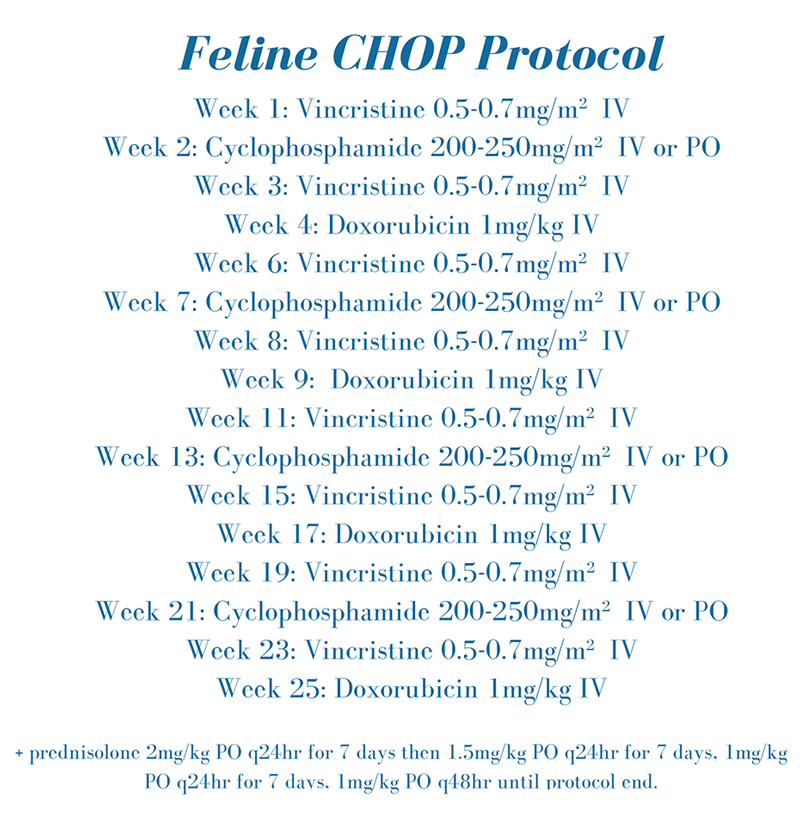

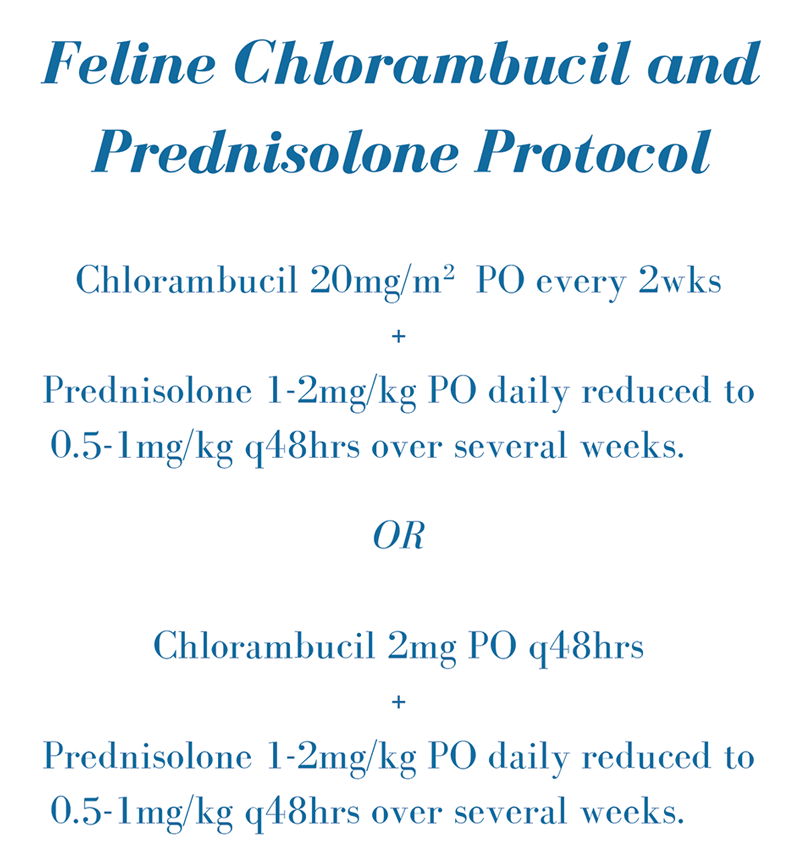

Intermediate and high-grade lymphomas are generally treated with a cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone (COP) protocol, or combined with doxorubicin in a cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (CHOP) protocol (Figures 1 and 2). Low-grade lymphomas are treated with chlorambucil and prednisolone (Figure 3).

The location of the tumour and staging results impact the type of treatment chosen.

Gastrointestinal lymphoma

Gastrointestinal lymphoma involves the gastrointestinal tract with or without lymph nodes and liver. Both high-grade (usually B-cell) lymphoma and low-grade T-cell lymphoma are common.

Intermediate or high-grade alimentary lymphoma is most often treated with a COP or CHOP protocol. Surgical excision is sometimes performed for diagnostic purposes, or to relieve acute obstruction, but it is unclear whether surgical excision improves survival times compared to chemotherapy alone. The median survival time for cats with intermediate or high-grade alimentary lymphoma treated with chemotherapy is only two months to four months1.

Low-grade alimentary lymphoma has a better prognosis and is easier to treat. Most cats (more than 90%) respond to a combination of chlorambucil and prednisolone, with a median survival time of two years or longer reported2,3.

At the time of relapse, many cats will respond to rescue therapy with chemotherapy, such as cyclophosphamide or lomustine.

Studies have evaluated small numbers of cats with alimentary lymphoma that received radiation therapy, as part of their initial treatment or rescue therapy4,5. Initial results are promising and this option could be considered for cats that have failed other therapy when a radiation therapy facility is available nearby.

Mediastinal lymphoma

Mediastinal lymphoma can involve the thymus, and mediastinal and sternal lymph nodes. It is often associated with pleural effusion. It is more common in younger, FeLV-positive cats with T-cell lymphoma. A median survival time of about two months to three months is expected with either COP or CHOP chemotherapy1.

A form of mediastinal lymphoma in FeLV-negative Siamese cats also exists. It appears to be less aggressive and more responsive to chemotherapy, with a median survival time of nine months6.

Nodal lymphoma

Lymphoma involving only the peripheral lymph nodes is uncommon. It is, however, quite common for other anatomical forms of lymphoma to involve the lymph nodes.

COP or CHOP chemotherapy is recommended as first-line therapy, with median survival times of about six months1.

Hodgkin’s-like lymphoma or T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma

Hodgkin’s-like lymphoma and T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma are uncommon forms of lymphoma that affect solitary or regional lymph nodes of the head and neck7,8.

Cats suspected clinically to have any type of solitary lymphoma should be thoroughly staged to ensure the disease is localised. If the disease is isolated then local therapy, such as surgery or radiation therapy, may be appropriate.

It is not clear whether adjuvant chemotherapy should be administered immediately after surgery, or whether frequent restaging and administration at the time of progressive disease or relapse is preferable. Survival times of a year or more are reported.

Nasal lymphoma

Nasal lymphoma is usually localised to the nasal cavity; however, about 20% of cats have nasal lymphoma extending beyond it9.

Thorough clinical staging is recommended at the time of diagnosis, including cytology of the mandibular lymph nodes, and thoracic and abdominal imaging (with and without bone marrow aspiration).

If disease is localised to the nasal cavity then radiation therapy is recommended. With radiation therapy, between 75% and 95% of cats are reported to achieve complete remission. Those that respond have a reported median survival time of about 18 months10.

Some clinicians, and pet owners, prefer radiation therapy because it is administered over three weeks to four weeks rather than a year (in the case of chemotherapy). However, a significant improvement in survival time for cats receiving radiation therapy compared to chemotherapy has not been proven10.

Chemotherapy is also a good option if it is more convenient for the cat to receive treatment in general practice. One study reported about 75% of cats with nasal lymphoma responded to chemotherapy, with approximately two years the median survival time for complete responders11.

Regardless of whether chemotherapy or radiation therapy is administered, cats with nasal lymphoma that do not respond to treatment tend to survive for two months to four months10,11.

If the disease is not localised to the nasal cavity at staging then COP or CHOP chemotherapy is the treatment of choice. Radiation therapy should not be used as the sole treatment.

Renal lymphoma

Renal lymphoma can present confined to the kidneys, or as part of gastrointestinal or multicentric lymphoma.

Renal involvement is generally bilateral and extension into the CNS is more commonly reported than with other lymphomas. Cytarabine, which crosses the blood brain barrier, is often added to a COP protocol to try to limit CNS spread. This is a cyclophosphamide, vincristine, cytosine arabinoside and prednisolone (COAP) protocol.

Cats with renal lymphoma tend to present with clinical signs of renal failure due to infiltration of the kidneys with lymphoma cells. Supportive care, in the form of IV fluid therapy and nutritional support, is often needed. However, signs of renal failure are not expected to resolve unless the lymphoma is successfully treated.

Chemotherapy is indicated as soon as possible after patient stabilisation. Doxorubicin should be given with caution as it is potentially nephrotoxic. For this reason, the author prefers either a COP protocol or a COAP protocol for these patients. Approximately 65% of cats with renal lymphoma are reported to respond to chemotherapy for a median of seven months11.

Chemotherapy practicalities

Most oncologists have a preference with regard to whether COP or CHOP is the best first-line treatment. However, the literature is inconclusive regarding the best protocol. Many general practitioners are not comfortable administering doxorubicin in general practice. A COP protocol should be administered where that is the case; it is well tolerated and side effects are not common.

Vincristine is administered at a dose of 0.5mg/m2 to 0.7mg/m2 intravenously. Starting at the low end of the dose range is an option, followed by an increase in dose if the first dose is well tolerated. Ultimately, we are aiming for the highest dose in this range that maintains excellent quality of life. Vincristine is administered though a “clean stick” IV catheter taped securely in place and checked for patency by alternatively flushing (0.9% sodium chloride) and drawing back blood (Figure 4).

Vincristine tends to be minimally myelosuppresive. Haematology to assess the neutrophil nadir is recommended seven days after the first treatment. If neutrophils are less than 2×109/L at this point, treatment should be delayed (if more is due). If neutrophils are less than 1×109/L, or if the patient is pyrexic, broad-spectrum antibiotics therapy should also be started. If a treatment is delayed, consider further reducing vincristine dosage by 10% to 20% to avoid future delays.

Gastrointestinal side effects following vincristine are uncommon and routine premedication with maropitant is not recommended. Prescribing oral maropitant at standard doses, for the patient to have at home if needed in the days following chemotherapy, is recommended instead.

Some cats may also benefit from ranitidine if they experience ileus associated with the chemotherapy treatment. Gastrointestinal signs more than five days after chemotherapy are unlikely to be related to treatment.

Cyclophosphamide can be given orally or IV at 200mg/m2 to 250mg/m2. Oral administration is simpler and usually preferred, assuming appropriately sized capsules are available for the bodyweight of the cat (or compounded capsules are available).

Gastrointestinal side effects are uncommon and routine premedication with maropitant is not recommended. Myelosuppression is rarely severe, but haematology should be performed seven days after the first treatment to assess the neutrophil nadir. Recommendations following neutrophil nadir results are as per aforementioned vincristine. Cats are not prone to developing sterile haemorrhagic cystitis; furosemide is, therefore, not routinely administered alongside cyclophosphamide.

When prednisolone 1mg/kg to 2mg/kg q24hr PO is administered as the sole treatment for lymphoma, survival times of two weeks to six weeks are expected. When it is administered alone, or as part of a COP protocol, prednisolone is very well tolerated.

When chemotherapy fails, consider other chemotherapy agents, such as doxorubicin (if a COP protocol was administered) or lomustine. The latter has been investigated in cats and is an appealing option because it is administered orally. However, responses tend to be short-lived12.

Chemotherapy is well tolerated in cats, but not always easy to administer. A cooperative patient is very important for IV chemotherapy and sedation is sometimes required to achieve this with minimal stress (Figure 5).

Summary

Many options exist to treat feline lymphoma in general practice. The drugs commonly used to treat both high-grade and low-grade lymphomas tend to be well tolerated and are not complicated to administer. Several options exist for oral therapy and the rate of side effects is low.

Chemotherapy is an option worth considering for many cats with feline lymphoma.

- Some drugs mentioned are used under the cascade.

Latest news