16 Jan 2024

Ultrasound-guided ethanol sclerotherapy for renal cyst in a springer spaniel

Lizzie Kwint explores a case of this procedure being successfully performed on a canine patient.

Image © Eliška / Adobe Stock

A patient presented to general practice with a history of reduced activity, temperament changes and a solitary episode of significant occult blood from the penis following urination.

A urinary dipstick showed no signs of on-going haematuria, and abdominal palpation showed some pain associated with the left kidney. Biochemical parameters were within normal range, and an ultrasound examination showed a large 4.1cm × 3.3cm solitary idiopathic cyst associated with the renal parenchyma. A double injection of 95% ethanol alcohol via ultrasound-guided ethanol sclerotherapy was chosen as an alternative to surgery in an attempt to ablate the cyst. This method has been found to have good long-term results and full resolution of the cyst in the majority of human cases, and has been reported previously in both dogs and cats for the treatment of solitary renal cysts.

This case report highlights that when performed by an experienced ultrasonographer, this method of treatment should be considered when treating idiopathic solitary renal cysts in both dogs and cats as an alternative to invasive surgery and nephrectomy.

Keywords: ultrasound, cysts, sclerotherapy, ablation

Renal cysts are rarely seen in dogs and more frequently seen in cats1. They can be bilateral or unilateral, and are generally fluid filled with an epithelial lining2,3.

These can be classified as simple or complicated, congenital, acquired or idiopathic. They do not contain infection or neoplastic material, and are generally not associated with any change in renal function unless obstruction of the outflow tract occurs2,4. Ultrasonography is a non-invasive and easily available method for diagnosis of renal cysts, and solitary renal cysts in dogs are generally found as an incidental finding. The pathophysiology of solitary renal cysts in dogs is not well described in literature. It is considered that those not associated with clinical signs of pain, hypertension or obstruction should generally be monitored3. Differentials for solitary idiopathic renal cysts in dogs would be familial polycystic kidney disease (PKD), seen in the bull terrier; familial nephropathy-related cysts in the shih tzu and Lhasa apso; and renal abscesses and haematomas (both of which may contain sediment or be more hyperechoic in appearance). If seen in the German shepherd dog, singular or multiple cystic lesions of the kidneys should raise concern of renal cystadenocarcinoma in this breed5,6.

In humans, symptomatic renal cysts are managed by ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage and placement of alcohol. Two applications of alcohol are performed, as it is thought that prolonged duration of contact with a sclerosing agent has a better reduction rate of recurrence in human patients compared to aspiration or a single alcohol injection in comparison3.

Complications of renal sclerotherapathy in human medicine are relatively low at around 1.7%7. Complications can be seen in the form of renal or abdominal haemorrhage, postoperative abscessation (less likely due to the high concentration of alcohol used in this procedure), postoperative pain, alcohol toxicity and rupture or bleeding in the cyst. Rupture or haemorrhage is generally seen if drainage is too fast, too large a volume of alcohol is introduced or if it is introduced too quickly into the cyst3,7. Hypotensive shock and death were seen after attempted treatment of a pancreatic pseudocyst in a poodle in one case7,8.

In humans, an average of more than 90% reduction of the cyst volume was seen in most cases. In one study, complete resolution occurred in 33% of cases and partial resolution of more than 90% size reduction occurred in 47% of cysts treated by alcohol ablation. Pain was significantly improved in all patients, regardless of complete or partial resolution9.

Drainage of the cyst and placement of 95% ethanol alcohol on two occasions has been proven to provide better long-term results, with minimal increase in risks10.

Case

Rupert, a seven-year-old, male neutered Welsh springer spaniel, presented to the clinic following one episode of occult blood from the penis following urination. His owner also reported slight lethargy over a two-week period and temperament changes prior to this, leading to mild aggression when approached by the other dog in the household. He also had a grade II/VI mitral valve murmur which was being monitored and considered not relevant to the current clinical presentation.

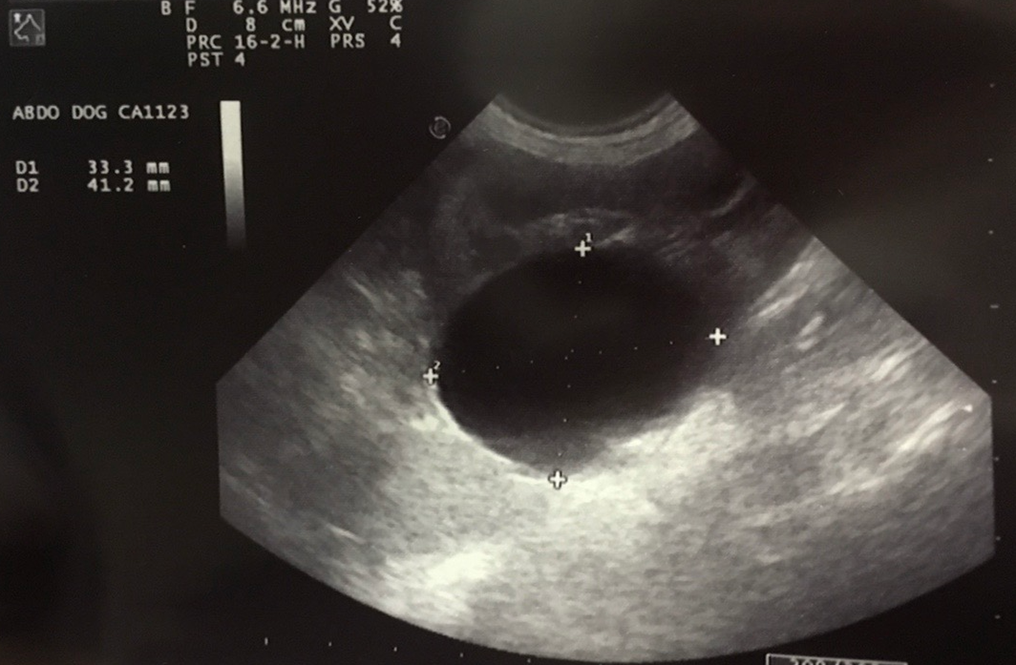

Clinical examination showed mild pain over the left kidney, but no other clinical changes. In-house biochemistry, haematology, urine dipstick and urine sediment were unremarkable, with all parameters falling within the normal reference range. Ultrasound was performed without sedation with a 6.6mhz probe and showed a left-sided 4.12cm × 3.33cm solitary parenchymal renal cyst (Figure 1). Concern was also shared regarding a small cyst on the right kidney, but this could be poorly visualised and was not present at follow-up ultrasound scan four weeks later.

Full biochemistry, haematology and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) were submitted for analysis, and all returned within normal parameters, except haematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), which all had minor increases, but that were considered non-significant at the time.

Treatment and follow-up

To perform sclerotherapy of the epithelial lining of the cyst, percutaneous drainage of the cyst and placement of 95% ethanol alcohol under general anaesthesia was performed.

Rupert was premedicated with butorphanol 0.10mg/kg IV and midazolam 0.1mg/kg IV, and was induced with propofol 4mg/kg IV. He was maintained on isoflurane.

The dog was placed in right lateral recumbency and the left flank was clipped and surgically prepared with chlorhexidine 4% solution diluted 1:10, followed by a final preparation with chlorhexidine and isopropyl alcohol.

Under ultrasound guidance using a 6.6mhz curvilinear probe, a 22g 3.5 inch spinal needle with a 50cm extension set attached to a three-way stop tap was placed into the interior of the cyst, and maintained in place for the full procedure. Using a three-way stop tap, 75% of the liquid was removed (15ml). This was classed as a transudate on in-house examination, but was sent for culture and cytology to rule out the risk of a neoplastic or infectious lesion.

Because of the use of 95% ethanol alcohol, the risk of postoperative infection and renal abscessation is very low, as it is hypothesised that the concentrated alcohol destroys any bacteria entering the cyst3.

After drainage, 5ml (ratio of 1:3 alcohol to removed volume of liquid) of sterile 95% v/v ethanol alcohol was injected slowly over two to three minutes into the cyst interior. This procedure needs to be performed slowly to reduce the risk of cyst rupture/leakage and reduces the risk of bleeding. This also allows the cyst to dilate adequately to allow even contact of alcohol with the cyst walls3,10.

The alcohol was left in place for five minutes, drained and again replaced with the same volume of alcohol, plus 0.5ml of lidocaine 1% to help comfort postoperatively. It was left for another 10 minutes and again drained. The position of the dog was moved slightly during the application period to make sure the entire lining of the cyst was coated10-12. This approach was chosen given the findings of damage to the adjacent tissue in another case after 20 minutes’ application time12.

‘Renal cysts in dogs are considered rare, and the pathophysiology is not well defined, unlike those seen in cats.’

On the second drainage of the injected alcohol, the 22g needle scratched the wall of the kidney, which caused mild haemorrhage. This resolved after a couple of minutes with no treatment. The needle was withdrawn under ultrasound guidance to monitor for leakage post-removal12. None was seen in this case.

The most common postoperative complication is pain at the injection site from leakage of alcohol on withdrawal, but this was not seen in this patient.

Postoperative blood samples were taken for full biochemistry, haematology and SDMA levels, and the dog was kept in hospital on Hartmann’s fluids at 4ml/kg/hour overnight for pain relief and monitoring of clinical signs.

All parameters came back normal and Rupert was returned to his owner the following day after a comfortable night and unremarkable recovery. He was given a five-day course of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid twice a day by mouth and the owner was instructed to give paracetamol and codeine (one-and-a-half tablets) twice a day by mouth for 48 hours after if needed.

The biochemistry was repeated a couple of days later and was again unremarkable. Cytology came back as a transudate consistent with a cyst. Bacterial culture of the cystic fluid was negative.

Ultrasound was performed on follow-up examination two weeks later without sedation, which showed no fluid filled structure, but a large granuloma or clot 3cm × 2cm was present where the cyst had been. The rest of the kidney looked subjectively normal.

The haematology, biochemistry and SDMA were repeated again at this stage, and remained unremarkable, although biochemistry did show a mild decrease in total protein and mild increase in urea 9.4mmol/L (1.7mmol/L to 7.4mmol/L).

The creatinine remained normal and SDMA remained within normal limits. Given that the dog was on a high-protein diet at the time and had eaten prior to blood sample, this was considered not of clinical concern. The HCT, MCV and MCHC had all returned to normal two weeks postoperatively.

No further blood had been noted in the urine and clinical examination showed no pain, and the owner reported a return to normal temperament at this time. Pain relief had only been needed for 24 hours after returning to the owner.

Specific follow-up ultrasound was not performed after this, given the good resolution of clinical signs, but six months later – when the dog presented for an echocardiographic examination for monitoring of mitral valve murmur – ultrasound examination of the kidney showed no evidence of recurrence of the cyst and minimal changes to the kidney.

Haematology and biochemistry for a routine health check the following year were completely normal.

Two years after the procedure, the dog presented to Cambridge Radiology Referrals for a CT scan using a 16-slice scanner following a short history of collapsing episodes unrelated to the heart. Pre-contrast and post-contrast CT scans noted no changes to the left kidney at all, and no evidence of a cyst or scar tissue, as seen in Figures 2 and 3. Blood results remain unremarkable two years on.

Discussion

Renal cysts in dogs are considered rare, and the pathophysiology is not well defined, unlike those seen in cats. The prevalence of idiopathic, single, uncomplicated cysts in dogs is not known at this time. In this case, blood and urine tests were unremarkable, and the only clinical signs were a single episode of occult blood from the penis post-urination and a change in temperament assumed to be pain related, as well as mild discomfort over the kidney itself.

SDMA remained normal throughout treatment, showing no compromise to the kidney itself, and urine concentration was within normal limits. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was not tested, given the apparently normal SDMA values. SDMA is a good minimally invasive method of monitoring kidney distress and, unlike GFR, requires only a single blood sample each time it is needed. This makes it easy to monitor in general practice.

Take-home points

Single, uncomplicated renal cysts in dogs are still considered rare and, as a consequence, further studies are needed to evaluate this technique in the veterinary field.

Alcohol sclerotherapy should be performed with the assistance of an experienced ultrasonographer.

Alcohol sclerotherapy has a quick recovery time and is a minimally invasive procedure with a good prognosis in humans3,9-12 and, so far, has also been seen in dogs3,4,12. Given that alcohol sclerotherapy is considered the gold standard treatment for symptomatic, single, uncomplicated renal cysts in humans, it should be considered a viable treatment option in single, uncomplicated renal cysts of small to moderate size in dogs.

- The procedure in this article was performed with the help of the author’s colleague, Johan Lategan.

Latest news