8 Jan 2018

Update on canine parvovirus

Canine parvovirus (CPV2) is the most common cause of hospitalisation due to diarrhoea in the UK. Diagnosis is relatively easy based on clinical signs, signalment, and biochemical and haematological parameters. Both ELISA patient-side tests and PCR laboratory testing for viral DNA are readily available and relatively cheap. Hospitalised patients may be treated effectively with a combination of fluid therapy, potassium supplementation, broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, appropriate nutritional support, antiemesis and gastroprotectants.

Severely ill patients may benefit from feline recombinant interferon and colloid therapy, although these treatments are not routinely used. Due to the contagious nature of the virus, strict isolation is required. The intensive nursing care and often lengthy periods of hospitalisation required may be expensive. Outpatient care can be appropriate in some carefully chosen cases, as per the University of Colorado protocol in areas where financial or other concerns preclude hospitalisation, although hospitalisation is preferable where possible.

Although vaccination against CPV2 is readily available and effective in its prevention, the disease is most common in areas with low levels of vaccination where financial concerns may also be present. Although CPV2 may prove fatal in 91% of infected puppies without treatment, survival rates of between 95% and 80% are possible with appropriate supportive care.

It is responsible for up to 58% of cases of severe diarrhoea requiring hospitalisation4 in the UK. This article reviews literature relevant to the general practitioner’s role in the diagnosis and treatment of CPV2.

What is CPV2?

CPV2 is a contagious enteric disease characterised by vomiting and acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea. The virus replicates in rapidly dividing cells – for example, intestinal epithelium. Parvoviruses are found in several species and are related to feline panleukopenia virus5.

How is it contracted?

Faecal shedding is the main source of infection, occurring from four to six days to several weeks following infection8. Transmission is assisted by profuse diarrhoea found in infected patients. Incubation of the virus is, on average, three to seven days3, and many natural infections are subclinical9. Puppies with sufficient maternally derived antibodies, and adult dogs with pre-existing antibodies, are less likely to develop clinical disease8, although unvaccinated puppies are particularly at risk following the decline of passively derived immunity.

Clinical signs and diagnosis

Presenting signs

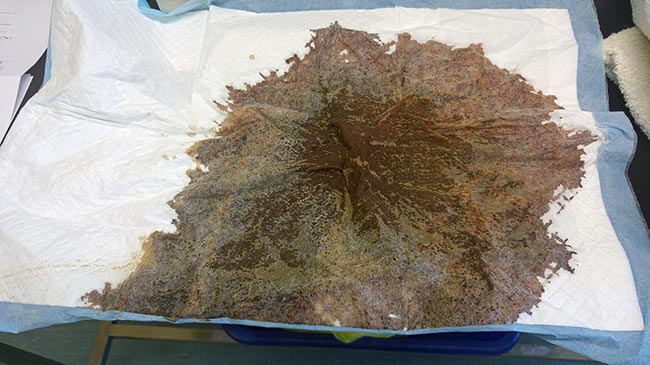

Neutropenia, vomiting and haemorrhagic diarrhoea3 are the hallmarks of parvovirus enteritis (Figure 1). This leads to hypovolaemia, dehydration, sepsis and collapse. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome consisting of three of the four following symptoms – a heart rate of greater than 140bpm, a respiratory rate of greater than 30bpm, temperatures of greater than 39.2ºC or lower than 37.8ºC, and white blood cell counts of greater than 17,000cells/μl or less than 6,000cells/μl – on presentation also indicates a poor prognosis10.

History

A high clinical suspicion can often be obtained through the history. Infectious gastroenteritis is suspected in dogs less than one year old with no history of vaccination that have recently been in contact with other gastroenteritis or confirmed parvoviral cases. Dogs presenting with severe depression and lethargy are more likely to test positive for parvovirus4 than relatively bright dogs.

Blood profile

Haematological and biochemical values are not diagnostic for parvovirus infection. However, certain values can increase suspicion of viral infection and influence prognosis. Leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypoglycaemia, hypoproteinaemia and hypoglobulinaemia are frequently seen in cases of CPV211. Lymphopenic and hypoalbuminaemic dogs have an increased length of hospitalisation10, compared to patients without these abnormalities. Continued leukopenia at 24 hours following admission is a poor prognostic sign12.

Patient-side testing

An ELISA assay (Figure 2), able to detect the presence of parvoviral antigen in a rectal swab within 10 minutes (Figure 3), is a commonly used patient-side test13. However, only 56% of positive samples are detected using patient-side tests7, probably because viral shedding begins four days after infection or because some cases only shed very low amounts of virus.

Faecal sampling for PCR testing is recommended for cases presenting with a negative patient-side test, but a high suspicion of parvovirus infection. PCR testing detects the presence of the parvovirus DNA and is far more sensitive than patient-side testing14.

PCR tests take one to three working days, exclusive of sample postage time. One alternative is to re-run the ELISA test in 48 hours in the hope antigen levels will have risen high enough for detection15.

Treatment and outcomes

Other therapies

Hyper-immune plasma, human recombinant granulocyte-stimulating factor, interferon, equine anti-endotoxin hyperimmune plasma antitoxin, recombinant bacterial/permeability increasing protein and oseltamivir have been described as treatment options in parvovirus cases, although all have failed to show a significant improvement in outcome6.

However, recombinant feline interferon has been used with success in one study to reduce mortality in CPV225.

Treating CPV2 on a budget

An outpatient protocol for managing dogs with CPV2 has been evaluated11.

Following IV fluid therapy and treatment for hypoglycaemia, dogs were given 120ml/kg SC fluid daily divided into three or four doses (40ml/kg, maropitant 1mg/kg SC sid, cefovecin 8mg/kg SC oral dextrose and potassium supplementation, if required – glucose and electrolyte parameters were measured daily) and four times daily syringe feeding of 1ml/kg oral canine convalescence diet. Patients that deteriorated on this protocol were hospitalised and treated in a conventional manner.

A total of 80% of dogs treated as outpatients in this manner survived to discharge, compared to a 90% survival rate in hospitalised patients receiving IV fluids, maropitant and cefovecin.

This method may help to reduce costs and provide care in a situation where hospitalisation is not possible, although diligent supportive care and frequent visits to the clinic are necessary26.

Sequelae

Perinatal parvovirus infection causes myocarditis and cardiac damage in young dogs infected with the virus within the first few weeks of life.

Vaccination protocols

CPV2 is considered a core vaccination. In puppies, maternally derived antibodies can interfere with the development of vaccine-derived immunity. WSAVA recommendations are to give at least two core vaccine doses to puppies and kittens, with the final dose of vaccine administered at or more than 16 weeks of age30.

If multiple vaccinations are not possible, for financial or cultural reasons, a single vaccination should be administered at more than 16 weeks of age. A booster injection should be given at 6 to 12 months, followed by revaccination at three-yearly intervals, or seroconversion testing. Although faecal parvovirus shedding is detectable for up to 28 days following vaccination with a modified-live vaccine8, no diagnostic interference occurs with in-house parvovirus testing31.

However, PCR tests carried out up to three weeks post-vaccination with a modified-live vaccine may detect viral DNA14, and, for that reason, a three-week interval is recommended between vaccination with a modified-live vaccine and PCR testing.

Conclusions

CPV2 is a common worldwide cause of gastroenteritis, accounting for up to 58% of hospitalised diarrhoea cases. Dogs less than one year old, with an absent or incomplete vaccination history, presenting with depression, lethargy and vomiting, with or without haemorrhagic diarrhoea, should raise clinical suspicions of parvoviral infection.

Patient-side snap ELISA and laboratory PCR tests are readily available for diagnosis, although dogs tested early in the course of the disease, or shedding small amounts of virus, may have a false-negative ELISA result and dogs vaccinated with a modified live parvovirus vaccine may have a false-positive PCR result for up to three weeks following vaccination.

Although not diagnostic, characteristic biochemical and haematological changes, such as neutropenia, lymphopenia, hypokalaemia, hypoglycaemia and hypoproteinaemia, may increase suspicion of the disease. Treatment relies on symptomatic and supportive care, and isolation protocols must be strictly observed to prevent spread of the virus.

Although CPV2 may prove fatal in 91% of infected puppies without treatment, survival rates of between 80% and 95% are possible with appropriate supportive care, and success rates of up to 80% have been achieved with appropriate outpatient protocols, even in cases where hospitalisation is not an option.

Treatment can be emotionally and financially demanding, with average hospital stays of five to seven days, thus it is important prognosis and cost are discussed at the time of patient admission.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the staff of Swaleside Veterinary Practice, Oscar’s owner for the photography and Andrew Kent for reviewing the article.