23 Jul 2018

Ventral neck mass in a dog

Francesco Cian discusses an aspirate from a mass on the ventral neck of an adult male dog in the latest in his Cytology Corner series.

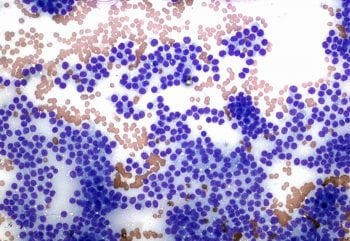

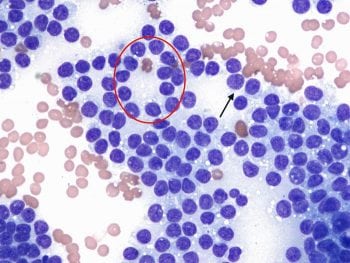

These pictures are from an aspirate from a mass on the ventral neck of an adult male dog (Wright-Giemsa stain 10× to 50×).

Description

The submitted smear is highly cellular with adequate preservation. The background is clear with frequent red blood cells. Large numbers of nucleated cells are present – the majority appearing as bare nuclei embedded in a background of lightly basophilic cytoplasm, with infrequent appearance of cytoplasmic membranes/borders (black arrow).

The submitted smear is highly cellular with adequate preservation. The background is clear with frequent red blood cells. Large numbers of nucleated cells are present – the majority appearing as bare nuclei embedded in a background of lightly basophilic cytoplasm, with infrequent appearance of cytoplasmic membranes/borders (black arrow).

These cells often form small clusters and occasionally show an acinar arrangement (red circle). Nuclei are round, with granular chromatin and poorly distinct nucleoli. Anisocytosis (cell size variation) and anisokaryosis (nuclear size variation) are mild, occasionally moderate. Rare blood-derived neutrophils are also seen.

Interpretation

The findings are consistent with thyroid neoplasm.

Comment

The presence of nucleated cells in the form of bare nuclei, often forming aggregates and occasionally showing acinar arrangement, is considered typical for a neuroendocrine neoplasia; the clinical history of a mass in the ventral neck area is highly suggestive of a thyroid origin.

Cytological features of atypia are overall mild; therefore, either adenoma or well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma should be considered in the differential list. The latter is more likely, since the vast majority (up to 90 per cent) of clinically apparent thyroid tumours in dogs are carcinomas.

These types of lesions may show an aggressive clinical behaviour, despite the mild features of atypia on cytology. In those cases – where cytology alone cannot be used to predict the behaviour of a lesion – other criteria must be used to differentiate adenomas from well-differentiated carcinomas, likely clinical (for example, size, degree of invasiveness and mobility of the mass and presence/absence of metastases) and histopathological.

These types of lesions may show an aggressive clinical behaviour, despite the mild features of atypia on cytology. In those cases – where cytology alone cannot be used to predict the behaviour of a lesion – other criteria must be used to differentiate adenomas from well-differentiated carcinomas, likely clinical (for example, size, degree of invasiveness and mobility of the mass and presence/absence of metastases) and histopathological.

Histopathology is also the diagnostic tool of choice in cases of haemodiluted and poorly cellular cytological samples, which are not an uncommon finding as thyroid tumours tend to have a high vascular density.

The biologic behaviour of canine thyroid tumours is well characterised. Thyroid carcinomas are invasive and will metastasise if given sufficient time (mostly to regional lymph nodes and lungs). The prognosis and potential for metastasis may depend on tumour size.

Where possible, surgical excision is the treatment of choice; however, carcinomas are highly vascularised, rapidly invasive and may invade local vital structures (such as jugular vein, carotid artery, oesophagus, trachea and larynx). Thyroid adenomas grow more slowly and are often clinically silent.

In dogs, hypersecretion of thyroid hormones in association with thyroid tumours is low (10 per cent) and most dogs are euthyroid. However, clinical hyperthyroidism may be rarely observed.

Latest news